Cascadia needs cleaner fuels to start decarbonizing heavy vehicles and industry. That means pushing biofuels to the max, and more.

These days Frank Lemos manages a shipping operation, but the former truck driver still gets behind the wheel occasionally to train new drivers or to fill a staffing hole. When he does, he notices a big difference. The firm recently moved away from conventional diesel fuel, and without it there’s something missing: the permeating petroleum smell that drivers wear after a day inside a big rig.

These days Frank Lemos manages a shipping operation, but the former truck driver still gets behind the wheel occasionally to train new drivers or to fill a staffing hole. When he does, he notices a big difference. The firm recently moved away from conventional diesel fuel, and without it there’s something missing: the permeating petroleum smell that drivers wear after a day inside a big rig.

“You come home and you don’t get to just jump in bed if you’re tired. You have to take a shower, or else someone’s going to kick you out of bed,” said Lemos, who is operations manager for Portland-based Titan Freight Systems.

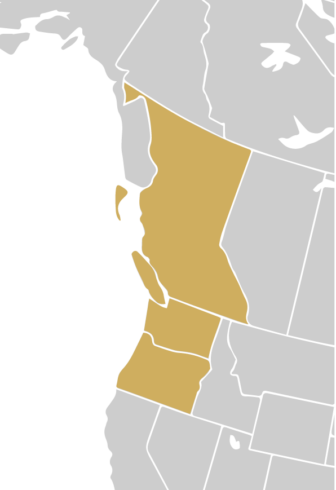

Since last fall Titan’s rigs, which deliver pallet-loads of goods between Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and Idaho, have mostly fueled up with renewable diesel, a biofuel made by refining vegetable oils, livestock tallow and cooking grease instead of crude oil.

It gets the job done just like petroleum diesel, yet generates far less air pollution. That’s not just a quality of life benefit. It means Titan’s drivers are breathing less toxic fumes and soot, and bringing less of that pollution home.

Lemos isn’t the only who’s noticed. Robert Bennett, Titan’s maintenance supervisor, said his wife quickly realized that she no longer needed to segregate his work clothes when she does the laundry. “There is definitely a big difference,” Bennett said.

Renewable diesel also yields far less of the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases driving climate change. That’s what inspired Titan’s shift.

The firm switched to renewable diesel one year ago, amid the region’s increasingly destructive wildfire seasons. Last year, a fire devastated the town of Phoenix, Oregon, just five miles from one of the firm’s terminals. “Doing nothing is not a course of action,” was how Titan president and owner Keith Wilson described his visceral response to the fires.

Wilson knew that climate change was stoking Cascadia’s fires, and that diesel vehicles produce over a third of Oregon’s transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions. Using biofuel cut Titan’s petroleum diesel consumption by 93% and cut its carbon footprint by over two-thirds.

Fuel pumps at Titan’s Portland terminal tap a 15,000 gallon tank full of renewable diesel, which is filled by fuels wholesaler. The low-carbon biofuel fuel is harder to access for smaller trucking firms that rely on retail fuel outlets. (Photo: Leah Nash)

Switching wasn’t a sacrifice. Wilson is getting renewable diesel at the same price. And the cleaner burn cuts maintenance costs, so he figures he’s actually saving about 2 cents a mile — over $20,000 a year.

Titan’s move is part of a Pacific coast wave driven by clean fuels standards enacted in California, Oregon and British Columbia. Their mandates and fees provide a $1 to $2 per gallon subsidy to renewable diesel and other low-carbon fuels, and their production is multiplying as fleets seek them out.

Washington state looks set to be next. After several failed attempts, the state’s House and Senate both approved a comparable program this spring, and were reconciling their bills at InvestigateWest’s press time.

To decarbonize, as climate science calls for, Cascadia will need an even stronger clean fuels push.

Recent research guiding Cascadia’s policymakers and industries finds that switching to battery-powered vehicles is the cheapest long-term solution to eliminate use of fossil fuels by 2050. Electrification can do it all for cars, energy planners say, edging out all but a fraction of conventional car sales within a decade.

However, electrification of fuel-thirsty heavy vehicles could take decades longer, and Washington, Oregon and British Columbia need to significantly trim carbon emissions by 2030. For those near-term carbon cuts, cleaner fuels — and lots of them — will be crucial.

Washington has mandated a 45% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. To get there, it needs to both electrify vehicles as rapidly as possible and meet over a third of the remaining fuel demand with low-carbon alternatives to petroleum, according to recent research for the state. That translates to over 1.7 billion gallons of clean fuels in 2030.

Energy experts call that a staggering volume.

“The scale is huge,” said John Holladay, who directs biofuels research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington. “It’s a very aggressive scenario.”

Cascadia’s clean fuels need dwarfs what’s now commercially available. Meeting the challenge means rapidly scaling up biofuels like renewable diesel and then doing more, because there simply is not enough plant- and animal-based material to support the volume required, say experts such as Holladay.

Making up the difference will require new fuels that are just beginning to take off — fuels such as hydrogen and low-carbon “synthetic” fuels. Governments and industries in Europe and Asia are beginning to push these next-generation fuels into their markets, while the U.S. and Canada lag behind.

Producing low-carbon fuels presents an opportunity for the region’s refineries, several of which have already begun to retool to make them. And energy experts say producing them locally will improve the reliability of Cascadia’s energy system.

But can clean fuels production ramp up as fast as the region’s climate action ambition demands?

On the Road to Electric Trucks

Electrifying vehicles, homes and industries is the cheapest way to provide the bulk of the greenhouse gas reductions required by 2050. Cars will shift quickly, thus cutting gasoline demand. Manufacturers such as General Motors have vowed to stop producing gasoline-fueled vehicles by 2035 or earlier, and the Washington Legislature just passed a 2030 target date for that transition.

But heavier vehicles such as buses, trucks, ferries and planes are harder to electrify. Production of battery-powered heavy vehicles remains limited, and the early models cost more and often carry less than conventional vehicles. Then there’s the need to build charging stations, which a report this month from the Environmental Defense Fund called “the greatest challenge of electrifying heavy-duty trucks.”

Wilson has extensively researched electric trucks, and hopes to introduce one to Titan’s fleet this year to learn more. But he figures it could take 20 years to turn over his diesel-fueled fleet. “Is it a short-term solution? My answer was no,” said Wilson.

Electrifying even beefier vehicles will take longer. Vancouver, B.C.-based Harbour Air vows to start operating its first electric seaplane in just a year or two. But even Harbour Air bets that it will be “decades” before battery-powered jumbo jets are crossing the continent.

“It’s still an emerging technology,” said Tyler Bennett, who manages decarbonization projects for Portland-area transit authority TriMet, which operates over 700 diesel buses.

The Portland-area transit authority is testing several electric bus designs as it works to eliminate diesel buses from its 700-plus bus fleet by 2040. But as TriMet works through software glitches and charging failures afflicting battery buses, diesel buses such as this one seen earlier this week still ply its routes. One of TriMet’s first moves was to acquire five battery-powered buses, and equip its Line 62 in Beaverton with North America’s most powerful overhead electric chargers. (Photo: Leah Nash)

Bennett said electric buses cost close to twice as much as diesel models and have shorter range. The first five buses TriMet acquired were mostly out of service last year, thanks to software and charging glitches.

So TriMet continues to add new diesel buses faster than it adds electrics. TriMet plans to cease purchasing diesel buses after 2025. Nevertheless, given the rate that equipment turns over — after 16 years of service for TriMet’s buses — Bennett expects diesels to still make up more than half of the fleet in 2030.

Which is why TriMet, like Titan, set its sights on switching to renewable diesel. Or, to be precise, “R99”: renewable diesel with 1% petroleum diesel added to help lubricate engines and to nab a $1 per gallon federal tax credit for fuel blends.

Bennett said tests on 32 TriMet buses in 2019 confirmed that using R99 cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40%. It also cut air pollution. That especially benefits lower-income and Black, Indigenous and other communities of color historically targeted for transportation corridors and therefore exposed to more diesel pollution. (Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality has estimated that diesel pollution kills about 460 Oregonians every year.)

And unlike earlier biofuels, using renewable diesel doesn’t require engine modifications. As Bennett puts it: “You pick up the phone and the company drops off R99 instead of diesel that day and you’re good to go.”

A renewable diesel price spike in 2019 prompted some early adopters to temporarily use more petroleum diesel. And that higher cost prompted TriMet to scuttle a long-term R99 purchase contract that was in the works last March when the pandemic struck. The transit operator tells InvestigateWest that it’s still assessing when it will make the switch, citing COVID-19’s “major impact on our finances.”

Renewable boom and limits

Growing experience of fleet owners — and the Pacific Coast’s clean fuel standards — have biofuels production ramping up. Renewable diesel dominates that growth. Production capacity under construction will roughly quintuple output in the U.S., and many more are in the works, according to a recent biofuels industry survey.

Much of the action is at oil refineries, including several in Cascadia, that are retooling to refine renewable feedstocks. In 2018, BP began mixing a little livestock tallow and vegetable oil into crude at its Blaine, Washington, refinery to make a lower-carbon diesel that’s 5% renewable — blending that could scale up and spread to Washington’s four other refineries if Gov. Jay Inslee signs a clean fuels bill this year as expected.

Calgary-based Parkland Fuel already blends in renewable feedstocks on a larger scale at its Vancouver-area refinery, where it expects to process over 600,000 barrels of tallow and canola oil this year — enough to make Parkland’s diesel up to 15% renewable.

The Parkland refinery near Vancouver, B.C., is changing its diet. Originally designed to convert Canadian petroleum and bitumen into jet fuel, gasoline, diesel and other fuels, it increasingly blends in renewable feedstocks. Doing so is necessary to remain in compliance with British Columbia’s clean fuel standard, which progressively reduces the average amount of climate-warming emissions allowed with the production and use of a gallon of fuel. (Photo: Alamy)

Canada’s Tidewater Midstream and Infrastructure, meanwhile, is among a growing number of refiners gearing up to produce pure renewable diesel. By 2023, a C$215 million to$235 million ($171 million to $187 million U.S.) expansion underway at its Prince George, British Columbia, refinery should be turning 3,000 barrels of renewable feedstocks per day into renewable diesel.

Dedicated “biorefineries” are also multiplying. A $1.5 billion-plus plant proposed for Columbia County, Oregon, not far from Portland, would turn up to 50,000 barrels per day of waste oils and fats into more than 500 million gallons per year of renewable diesel. Its proponent, NEXT Renewable Fuels, has applied to be exempted from siting approval under a state law incentivizing low-carbon biofuels.

The question is how many refineries can be sustainably supplied with oils and fats. “The amount we need is not consistent with the amount that’s available,” according to Holladay.

So, where to turn? As the supply of waste fats taps out, biofuels producers will rely more heavily on vegetable oils. That may drive up food prices and reduce the climate benefit.

Making fuel from waste fats provides a double benefit by preventing those wastes from simply decomposing, a process that releases the potent climate pollutant methane. In contrast, turning to harvested plant oils could drive consumption of palm oil, whose rising production has led to rainforest destruction in countries such as Indonesia. Clearing forests for palm plantations undercuts climate benefits.

Operators such as NEXT Renewable Fuels have explicitly sworn off using “virgin” palm oil. But tracking the palm oil supply chain is difficult.

Growing demand for palm oil contributes to rapid destruction of rainforests in Indonesia, Brazil and other tropical countries, and the resulting loss of forest carbon defeats the climate benefits of producing biofuels from palm oil. Several studies also have correlated forest clearing for palm plantations with the transfer of wildlife disease to humans. (Photo: Shutterstock)

To hydrogen and beyond

Experts project that meeting clean fuels demand in 2030 will take clean fuels producers into new technologies and ingredients that are on the cusp of commercial production today.

One potential source of future fuels are abundant biomass materials such as wheat chaff and other agricultural leftovers, sludge from sewage treatment plants, and small trees from thinned-out forests. Biomass can be converted to methane gas and compressed to fuel vehicles. Alternatively, superheated water and catalysts — materials that accelerate chemical reactions — can turn biomass into an oily mix known as “biocrude” that refineries can take on.

Holladay and collaborators at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Washington State University are working to demonstrate the feasibility of the biocrude fuels chain. They are making biocrude from a blend of sources including wastewater sludge from Detroit and food wastes from a prison and an army base in Washington state.

Last month, they reported continuous conversion of biocrude to renewable diesel for over 2,000 hours with no damage to the particularly pricey catalysts that refineries employ.

The PNNL-WSU research could play a small role in the set of next-generation clean fuels endorsed by Washington state’s 2021 energy strategy: hydrogen gas made with renewable power, and liquid fuels produced by reacting that “green” hydrogen with a range of materials.

Cascadia’s first green hydrogen project broke ground in March at the Douglas County Public Utility District in central Washington. The plant will use hydropower generated at the utility’s Columbia River dam to split water into hydrogen gas and oxygen.

Electrolyzers use electricity to split water into combustible hydrogen gas and oxygen. If the electricity used is renewable, the resulting “green hydrogen” is a zero-carbon fuel that can replace fossil fuels for industries, heavy vehicles, and other energy uses that are difficult to plug in to the power grid. As Cascadia makes greater use of wind and solar energy, stores of green hydrogen can also be tapped to generate electricity, providing a backup power supply during extended dark, windless periods. (Photo: Cummins)

Such hydrogen can replace natural gas and coal that fuel industries, or be used to propel electric vehicles that get their power from fuel cells instead of batteries. Fuel cells are electrochemical devices comparable to Douglas PUD’s hydrogen plant, but running in reverse to combine hydrogen and oxygen and thus generate electricity.

Toyota, which along with Hyundai and Honda already sells fuel cell vehicles in California and British Columbia, is teaming up with Douglas PUD to open a market in Washington by building the state’s first hydrogen fueling station near Centralia.

Douglas PUD expects to get an extra boost from its hydrogen production: flexibly adjusting the plant’s operation to keep the power supply and demand in balance. (See Using hydrogen to back up the grid)

Another way to use hydrogen to beat climate change is to produce low-carbon liquid fuels. Those include diesel for use in heavy vehicles and jet fuel for jet engines. A firm in Quebec is building one of the world’s largest green hydrogen plants, about 17 times bigger than the one at Douglas PUD. It will convert nonrecyclable municipal waste and wood waste into biofuels.

Decarbonization modeling supporting Washington’s new energy strategy found that hydrogen-derived fuels could account for four-fifths of the state’s clean fuels supply in 2030. Projections like that are new for North America, but they are the new normal in Europe and Asia where large renewable hydrogen projects are multiplying.

A Danish renewable energy giant, Ørsted, is laying plans for a hydrogen plant 200 times larger than Douglas PUD’s, to be powered by a dedicated offshore wind farm.

Banning petroleum

Cascadia’s clean fuel standards have started a transition to low-carbon fuels. But those programs are not sufficient to deliver the hydrogen and clean fuels industries needed by 2030.

Big investments promised by the Biden Administration could help. An infrastructure plan unveiled by Biden last month promises $15 billion toward large demonstration projects for emerging energy technologies, including 15 hydrogen projects.

The uncertain cost of hydrogen-based fuel processes means it is hard to predict which fuel pathways will ultimately scale up, according to Jeremy Hargreaves, the energy systems modeler with San Francisco-based Evolved Energy Research who led the recent research for Washington state.

What’s certain, said Hargreaves, is that the hydrogen fuels will cost considerably more than today’s commercial fuels, such as renewable diesel. Which is why electrifying as fast as possible rose to the top of the strategy menu that Hargreaves’ firm evaluated for Washington state, and in similar studies for British Columbia and Oregon. It makes sense to electrify as many cars and trucks as possible before turning to the more-expensive green hydrogen fuels.

Environmentalists worry that expanding clean fuels production will actually undermine that effort, undercutting the early market adoption of electric vehicles.

“You are providing an incentive to continue using fossil-powered trucks and ferries, rather than shifting to electrified equivalents,” said Patrick Mazza, a Seattle-based environmental activist and energy analyst.

Many worry that hydrogen-based fuels could also spur new fossil fuel production. Right now, green hydrogen is pretty expensive. It’s much cheaper for the time being to continue using a climate-unfriendly process using natural gas that is responsible for over 2% of global carbon dioxide emissions.

Even if some of the carbon emissions could be captured, making more hydrogen from natural gas would spur continued fossil gas drilling and the associated methane leaks.

“You are giving a new market to fracked gas, with all its air and water pollution problems, as well as questionable carbon benefits,” said Mazza.

In contrast, the concern of trucking mini-magnate Wilson at Titan Freight Systems is about ensuring that Cascadia starts getting trucks off petroleum today.

Titan Freight Systems president Keith Wilson spent a decade trying to cut his trucking firm’s carbon emissions, and failed. Energy-sapping pollution-control equipment needed to capture soot and other toxic emissions mostly negated Titan’s fuel efficiency upgrades, such as aerodynamic trailers. So last year, Wilson switched strategies, replacing petroleum diesel with cleaner-burning, lower-carbon renewable diesel. (Photo: Leah Nash)

Wilson spent this winter educating fellow carriers and the Oregon Trucking Associations on renewable diesel’s advantages. Then, hot off an unsuccessful 2020 bid for Portland City Commission, Wilson leapt back into politics this year, proposing a state law to phase out petroleum diesel by 2028.

Wilson’s bill got a frosty reception from Oregon Republicans, who have made a habit of fleeing the Oregon State Capitol to block climate legislation. The trucking association raised fears of renewable diesel shortages and price spikes. So Wilson and Democratic State Rep. Karin Power, who formally introduced the bill last month, added several safety valves to the bill designed to head off steep price hikes.

Wilson positions his bill as a cost-saving measure that can improve health, grow jobs, and reverse nearly a decade of rising carbon emissions in Oregon. And, he says, those wildfires are costing him customers. “We’re being compromised when we lose entire communities because of fire or smoke in the summer, because people aren’t buying fishing gear,” said Wilson.

Frank Lemos, Titan’s operations manager, says his concern is managing the backlash that’s likely to come from Wilson’s proselytizing for climate action. He wants a cleaner workplace for his drivers, and he accepts that getting off fossil fuels is important for his drivers’ grandkids.

But he also needs to protect his drivers from the inevitable blowback from their industry counterparts, whether it’s chatter on the CB radio or at the truck stops. He expects those conversations to go sideways, with their drivers hearing that costs will rise and Titan will have to cut their wages, or their jobs.

“You don’t want to be thought of as that guy from that company who’s trying to change the way trucking is done,” said Lemos. “Nobody wants to be that scapegoat that makes the difference. But somebody has to be.”

This story is supported in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Feature image: Frank Lemos manages regional operations for shipping firm Titan Freight Systems, but still dons a uniform sometimes to move a truck between terminals or train a driver. He calls climate change “a big weight on everybody’s shoulder,” but says fuel costs matter too because trucking is critical to the economy: “You start messing with transportation in this world and it could get ugly really quick.” (Photo: Leah Nash)