Employees at Cornerstone Cottage alerted state officials to the dangers, only to be fired themselves

By Wilson Criscione / InvestigateWest

Before Emily Carter called back her boss, she pressed “record.”

Jim Smidt, the owner of a residential facility for girls called Cornerstone Cottage, wasn’t happy with her, and he wanted to talk.

“We are going to go ahead and terminate your employment here with us at Cornerstone,” Smidt said.

“OK,” Carter said. “Could I ask why?”

“Um, we’re really not under any obligation to explain why,” Smidt said. “We just feel like it’s time to do that.”

Carter was sure she knew why. Days earlier, she and four other employees sent an 84-page complaint to Idaho state regulators detailing horrors against children at Cornerstone Cottage: a girl being sexually assaulted, another with autism purposely taunted in order to justify sending her to a hospital, and yet another girl who strangled herself repeatedly, nearly to death, while workers were told not to help until she passed out.

Carter, then a 23-year-old recent college graduate in 2021, knew that filing the complaint might cost her her job. But it would be worth it. Now, she thought, the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare would finally step in and put an end to the unspeakable things happening to girls at Cornerstone.

She was wrong.

By 2020, Emily Carter was fresh out of college and wanted to make a difference for girls who were like her, so when she saw the job opening at Cornerstone, she went for it. (Leah Nash/InvestigateWest)

YEARS OF PROBLEMS

Cornerstone Cottage opened in 2016, blocks from the interstate in Post Falls, Idaho, a booming bedroom community 25 miles east of Spokane. From the outside, the building could be mistaken for a suburban home. It’s staffed with several members of the Smidt family, and the facility accepts girls 11 to 17 who typically have been through extreme trauma and are in foster care.

Programs like Cornerstone, part of what’s referred to as the troubled teen industry, capitalize on a nationwide foster care shortage and states’ failures to provide mental health treatment to youths. It’s one of 28 private residential facilities in Idaho that accept taxpayer dollars to house and treat children, and since it opened, it’s collected roughly $7.5 million from foster care agencies in Idaho and Washington alone. That’s in addition to the money they get from private payers or other state agencies that send children there.

In recent years, though, the troubled teen industry has come under intense scrutiny. Abuse and deaths of children have plagued these facilities, and other states have boosted regulations and shut programs down.

Idaho has been reluctant to follow suit. Idaho’s Department of Health and Welfare, the state agency with oversight authority, said it could not point to any time it suspended or shut down a children’s residential facility.

Yet as state regulators have stood by, children at Cornerstone have repeatedly found themselves in harm’s way, an InvestigateWest review of state records, internal company messages and interviews with former employees has found.

The Pacific Northwest needs facts. Help us report them.

Yes, I’ll donate today.

Independent investigative reporting needs your support. InvestigateWest delivers fact-based journalism to our region by people who live and work here — and our community of readers make it possible. Will you support our nonprofit newsroom with a donation?

Cornerstone says it’s a “trauma-informed,” “secure” and “culturally sensitive” facility for girls who need inpatient treatment from a “professionally trained” staff.

The reality, based on accounts from former employees, residents and public records, appears to be very different.

One girl was raped by a staff member. Others were attacked, molested or berated. Girls fought and sexually assaulted each other, with one being continually called racial slurs and harassed because of her race. Several chewed and swallowed shards of glass as if they were ice and had to be hospitalized. Others attempted suicide again and again.

The staff who spent the most time with the girls had little to no experience working with kids and were paid less than $15 an hour, former employees said. For years, they didn’t have the mandated training to handle children who were a threat to themselves or others, state records show. Nor did they have proper training on child abuse and neglect protocols.

Police were there frequently breaking up fights, returning runaways or putting on handcuffs because staff couldn’t handle dangerous situations on their own. From 2017 to 2022, Post Falls police were called by Cornerstone Cottage 321 times, just over once a week on average, call logs show. It’s a significant number considering Cornerstone’s relatively small size — with only 16 beds — compared to other Idaho facilities. Boise Girls Academy, for comparison, has averaged less than one police call per month since 2018, records show, but its capacity is three times that of Cornerstone.

By 2021, when Carter and the others filed their complaint with state officials, regulators already knew about some of this. Over the years, however, the state had chalked up organizational failures that put children in life-threatening situations to correctable policy violations.

Still, their complaint initially caught the state’s attention. Investigators verified, among other things, that staff hadn’t received proper training, that there were incidents where staff hit or used violent force on a child, that some of those incidents weren’t properly reported, and that there were environmental hazards in the facility. In its first five years, Cornerstone committed 111 licensing rule violations, according to Idaho’s official statement of deficiencies.

The state, however, took no disciplinary action other than a three-month freeze on adding new kids to the site until the issues were addressed in a way that satisfied regulators. It hardly affected Cornerstone at all.

In an interview with InvestigateWest, Smidt acknowledged that, in hindsight, not everything has gone “perfectly well” at Cornerstone. But he stressed that he and his team have always done their best to care for girls with severe behavioral issues. He maintained that all employees are trained to handle dangerous situations and claimed that the state’s repeated findings indicating otherwise were merely Cornerstone’s record-keeping errors.

In fact, Smidt took the state’s lack of enforcement as evidence that Cornerstone was doing something right.

“Certainly they would have taken away our license, or they would have sanctioned us, or done something, had they felt that any of the major concerns were a problem,” Smidt said. “But that never happened.”

That’s why, for Carter, being fired that day in 2021 was only the beginning. Because for her, it’s bigger than any one facility.

“I don’t know how you could ever say that one of them is safe or effective if what happened at Cornerstone was acceptable, to the point that they still have a license,” Carter said.

ACCESS TO GIRLS

Officially, according to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, Cornerstone violated the rules related to employee training, background checks, and maintaining an environment that is “safe, accessible, and appropriate for those served.”

While from the outside, Cornerstone Cottage could be mistaken for a suburban home, Post Falls police received 321 calls from Cornerstone Cottage from 2017 to 2022. (Erick Doxey/InvestigateWest)

Nothing in the 2017 “statement of deficiencies” report from the state, however, said what actually happened: A Cornerstone staff member raped a 16-year-old girl who lived there.

In the summer of 2017, Bradley Ott hadn’t been hired yet by Cornerstone when a friend of his who already worked there invited him to come to a movie theater. That friend had with him three girls from Cornerstone.

One of them was the girl Ott would later be charged with raping.

Ott, then a 21-year-old who knew Smidt from church, got a job at Cornerstone soon after. Cornerstone gave him unsupervised access to girls without reviewing his references, properly checking his criminal history, making sure he had a valid driver’s license or having him complete the required 25 hours of training that includes guidance on boundaries and child safety, records show.

Within weeks, he and the girl hatched a plan for her to escape out her bedroom window. She snuck out that way four times, each time at 11:20 p.m., when they knew other Cornerstone staff wouldn’t notice she was gone. They drove around in his truck and listened to music, police records show. She thought they were in love.

The last time, three other Cornerstone staffers who were socializing after work happened to recognize Ott’s truck in a grocery store parking lot. As they approached, the girl tried to duck down to avoid being caught, but it was too late.

Ott confessed to the employees that night, and later to police, that they’d had sex — rape, per Idaho law, because she was 16 and he was three or more years older. He was fired, and then arrested and charged with rape. (Ott, reached by InvestigateWest, did not dispute the facts of the case, adding that he knew it was illegal at the time and his emotions overpowered his logic.)

It wasn’t someone from Cornerstone who first notified police. A day and a night had passed before a state caseworker followed up on an incident report describing what happened over the weekend. She reported it to law enforcement, adding that Cornerstone told her “they would not be contacting the police until they do their own investigation,” per court records. Hours later, Smidt notified police.

Ott pleaded guilty to the crime in what Kootenai County Judge Lansing Haynes acknowledged was a “lenient” deal, according to audio of a 2018 hearing. The deal downgraded the charge to injury to a child, then allowed Ott’s record to be scrubbed clean once he completed probation. The victim, today, is in an Idaho prison on drug possession charges. She did not respond to messages seeking comment for this story.

From the bench, Judge Haynes blasted the decision to hire Ott with no requirements other than “a good heart and good intention.”

“I just can’t imagine a worse scenario than a facility to bring uncertified and untrained young men in to be intimately accessible to troubled teenage girls, and hope for the best,” Haynes said. “Obviously, that didn’t work out in this situation.”

State regulators required Cornerstone to correct its hiring and training practices, but took no disciplinary action against the facility.

‘CHANCE AT A FUTURE’

Two years later, Jim Smidt’s voice cracks as if he’s holding back tears. The audience of his local TEDx Talk listens intently. Clean-shaven, his blonde hair in a crew cut, Smidt heaps praise on the caregivers who work with teenage girls every day at Cornerstone.

“They’re underpaid, and they’re overworked, and they get the crud kicked out of them by these kids,” Smidt said. “They do it because they have developed the ability to see beyond the behavior, and to find out why, and to help them and love them … to give them a chance at a future.”

Smidt has been held up as an effective mentor for teenage girls. In 2009, he and his wife were featured on an episode of the TV show “World’s Strictest Parents” for their handling of two “disrespectful” teenagers. But he tells the audience in 2020 that it’s the staff members who deserve all the credit for making a difference for the girls at Cornerstone.

“Eighty-seven percent of the kids that come into our program under these circumstances walk out showing marked improvement,” he said to applause.

That didn’t match the experience of many girls who went to Cornerstone seeking help.

On Slack, a messaging platform used by Cornerstone, employees frequently posted updates about girls being sent to the hospital or put in handcuffs due to self-harm behaviors or violent outbursts. Former employees told InvestigateWest that mental health treatment happened once a week at most — far less than experts say was necessary. Smidt counters that staff wasn’t always aware of the work therapists were doing with the kids.

Mara Deloney was first placed at Cornerstone in 2016. She’d been in foster care following the death of both her parents and was told she needed inpatient treatment to address her angry outbursts.

Deloney’s stay at Cornerstone wasn’t all negative. In fact, she preferred it over other residential facilities she went to — something she attributes more to the problems with the entire troubled teen industry than to Cornerstone itself.

But she said Cornerstone also caused her lasting damage: Another girl attacked her, and Deloney suffered a traumatic brain injury that to this day causes migraines. It could have been prevented if staff had known how to step in and properly restrain the girl, Deloney said. (Smidt declined to discuss specific cases of girls for privacy reasons.)

Mara Deloney was first placed at Cornerstone in 2016. And though she preferred it to some other residential facilities, she also said Cornerstone caused her lasting damage, including a traumatic brain injury that to this day causes migraines. (Young Kwak/InvestigateWest)

Meanwhile, police were routinely showing up to diffuse situations. In 2017, Post Falls police even complained to the state about it, believing it reflected the staff’s inability to handle the kids’ behavior.

“As someone who grew up in a very traumatic environment,” Deloney said, “it was very traumatizing.”

In 2020, an 11-year-old who’d been through severe trauma was sent to Cornerstone from Washington. At Cornerstone, the girl, who is Black, was constantly bullied by other girls. They called her racial slurs and compared her to animals. One resident threatened to kill her because of her race, according to company Slack messages and records. Management, records show, tried to address the harassment through therapy with the girls who threatened her instead of calling police and reporting it as a crime.

Staffers also mistreated her, calling her “ghetto,” “sassy,” “stupid” and “retard,” according to Carter and other employees who worked at Cornerstone at the time. One worker grabbed and squeezed the girl’s chest in a sexual manner, they said, while another employee put her hands around her neck “in an attempt to strangle or fight her,” records show. Both were later fired.

The girl was supposed to be discharged from Cornerstone at the end of January 2021, but a week before that, she had an episode in which she attacked and injured staff members. They called the police for help, and the girl, then 12, got out of Cornerstone only to end up behind bars.

Carter felt powerless to help her.

“I just struggle to figure out what Cornerstone was supposed to be doing for these kids,” she said. “They all obviously got worse.”

A ‘STUPID IDEA’

Carter thought she knew what an abusive facility for kids looked like. As a teenager in 2014, Carter’s parents sent her to a therapeutic boarding school called Clearview Horizon in Montana — a couple hours’ drive from Cornerstone.

What happened there scarred her. Carter describes it as brainwashing, where kids faced strict discipline and sometimes weren’t allowed to speak. They were routinely punished by being forced to run up and down a steep hill for hours. Carter later became part of a lawsuit, alleging psychological manipulation, food deprivation, corporal punishment and solitary confinement at the school. That case is pending.

By 2020, Carter was fresh out of college and needed a job during the pandemic. She wanted to make a difference for girls who were like her, so when she saw the job opening at Cornerstone, she went for it. People couldn't understand it, but Carter believed Cornerstone was different from the draconian school she went to as a teen. Cornerstone, by contrast, was more laid back and allowed girls more freedom. It took kids in foster care, not only private payers, so she thought it would have more oversight. One of the supervisors had actually gone to Clearview with Carter — surely, Carter thought, the supervisor wouldn’t let anything bad happen.

And Carter had a plan in case anything bad did happen — one that seems silly now looking back, Carter said.

“I had this stupid idea that if I see child abuse, I’ll just report it,” Carter said. “That I’ll do what I’m supposed to do, and it’ll be fine.”

It wasn’t just Carter who saw problems at Cornerstone. It was obvious to others, too. Some rooms where girls lived had missing baseboards and feces spread on the wall, records show. On Slack, staffers noted sharp objects accessible to suicidal children.

Most concerning, though, was how girls were regularly putting themselves or others in life-threatening situations. Some of it was to be expected, considering the reasons the girls were sent there in the first place. Still, former staffers recalled being discouraged from calling police while also lacking the tools to de-escalate situations on their own. As a result, they feared for their own safety and the safety of the girls.

Idaho has rules in place on how to safely intervene in life-threatening instances. Physical restraint techniques are to be used briefly, and only to keep kids safe, and only by employees who have been trained and authorized by a nationally recognized program to use those techniques. Yet despite the state’s yearly inspections and reports of violent incidents occurring at the facility, it wasn’t until the 2021 complaint by Carter and others — five years after Cornerstone opened — that regulators discovered none of the direct care staffers at Cornerstone were actually certified to use physical restraints.

Instead, staff sometimes used “expressly forbidden” prone restraints to subdue girls, the state would later find. That technique involves a child lying face down with the adults on top.

Samantha George, a former employee, said when she first started at Cornerstone in 2018, she and a co-worker were instructed by a supervisor to hold a girl in a prone restraint. They held her there for four hours, George recalled.

“I have deep regret for following through on those actions,” George said. “I was brand new and did not know what I was doing.”

There were other life-threatening situations, the employees said, that regulators never knew about. George said she once wrote an incident report, thinking it would be sent to the state regulators, when a girl choked herself to the point of unconsciousness. George said a supervisor had her take out the word “unconscious.” The incident was not investigated as alleged child neglect, records show.

“Those self-harm incidents should have been reported,” said George, who’s now a licensed therapist in Washington. “Part of the reason they were able to successfully harm themselves — and thank God they did not kill themselves — was due to neglect of the staff in the facility.”

Carter didn’t know that anyone else shared her concerns until late 2020, when she talked to a co-worker named Caley Hickey. They were both frustrated that another staff member had repeatedly been too physical with kids, trying to fight them or choke them, and management wouldn’t stop it.

“I knew these things weren’t right. I would watch all these things happen. And then I would go to management, and nothing. There was nothing done about it,” Hickey said.

Emily Carter, left, and Kieria Krieger both worked at Cornerstone Cottage and, with other colleagues, sent an 84-page complaint to Idaho state regulators detailing horrors against children at the facility. (Leah Nash/InvestigateWest)

Finally, weeks later, that staffer slapped a child in the face and was fired. But Cornerstone did not report the abuse to the state within the required 24 hours — a violation the state ignored initially.

Hickey and Carter continued to trade stories about times they jumped through traffic chasing girls who’d escaped, begging supervisors for permission to call the cops for help. Each time, they were instructed to file an incident report and go back to work.

Then Carter spent more time with Kieria Krieger, another co-worker, on a road trip to pick up a child. During that car ride, Krieger brought up Bradley Ott.

“You know I’m the one who found [the girl] in the car with him, right?” Carter recalled Krieger saying.

Carter was shocked. And she couldn’t believe that Krieger — and the other two employees she had been with — hadn’t immediately called police, and that police never interviewed her. Carter explained mandatory reporting rules, which say that anyone must report suspected child abuse or neglect to the state or law enforcement within 24 hours. Krieger said workers were instead told to simply inform management if they suspected child abuse or neglect, not knowing if those reports made it to law enforcement or state regulators.

If that’s the law, Krieger told Carter at the time, then there’s a lot more they need to tell authorities.

They formed a team. Carter, Krieger, George, Hickey and a former employee started a group text, compiling everything they felt the state needed to know — accounts of more physical and sexual abuse by staff or residents, medical neglect, inappropriate restraints, harassment and failure to follow reporting protocols. Carter put the complaint together and sent it to the state on Jan. 27, 2021.

“We were at this point where it’s life and death. We needed that oversight that we should have had before,” Krieger said. “We needed somebody to come in and save these kids, man.”

TROUBLED TEEN INDUSTRY

Children typically end up at a place like Cornerstone because nobody else can take care of them. They’re sent away, sometimes from across the country, because their own parents fear them, or because schools don’t have the means to support them, or because the foster care system has no bed for them.

These for-profit programs — therapeutic boarding schools, residential treatment centers, wilderness programs — promise to not only accept these kids, but to treat them.

But many states are starting to crack down on these facilities after seeing what actually happens inside. Montana recently strengthened regulations for youth residential facilities after reports of child abuse and neglect going unchecked.

Even Utah, considered the nation’s epicenter of the troubled teen industry, and hammered in the past for allowing abusive facilities to operate, has increased regulations. Earlier this year, Utah state regulators said they would not renew the license of Diamond Ranch Academy, where a 17-year-old from Washington named Taylor Goodridge died in December 2022. Goodridge had been vomiting for days and was not taken to a hospital before dying of a treatable medical condition.

Idaho shares qualities with Utah that make it attractive to those who want to open a troubled teen program. Both have relatively cheap land that’s often outside urban areas. And both give parents the right to force children under 18 into treatment, even if the children object. (In Washington, by contrast, the age of consent is 13.)

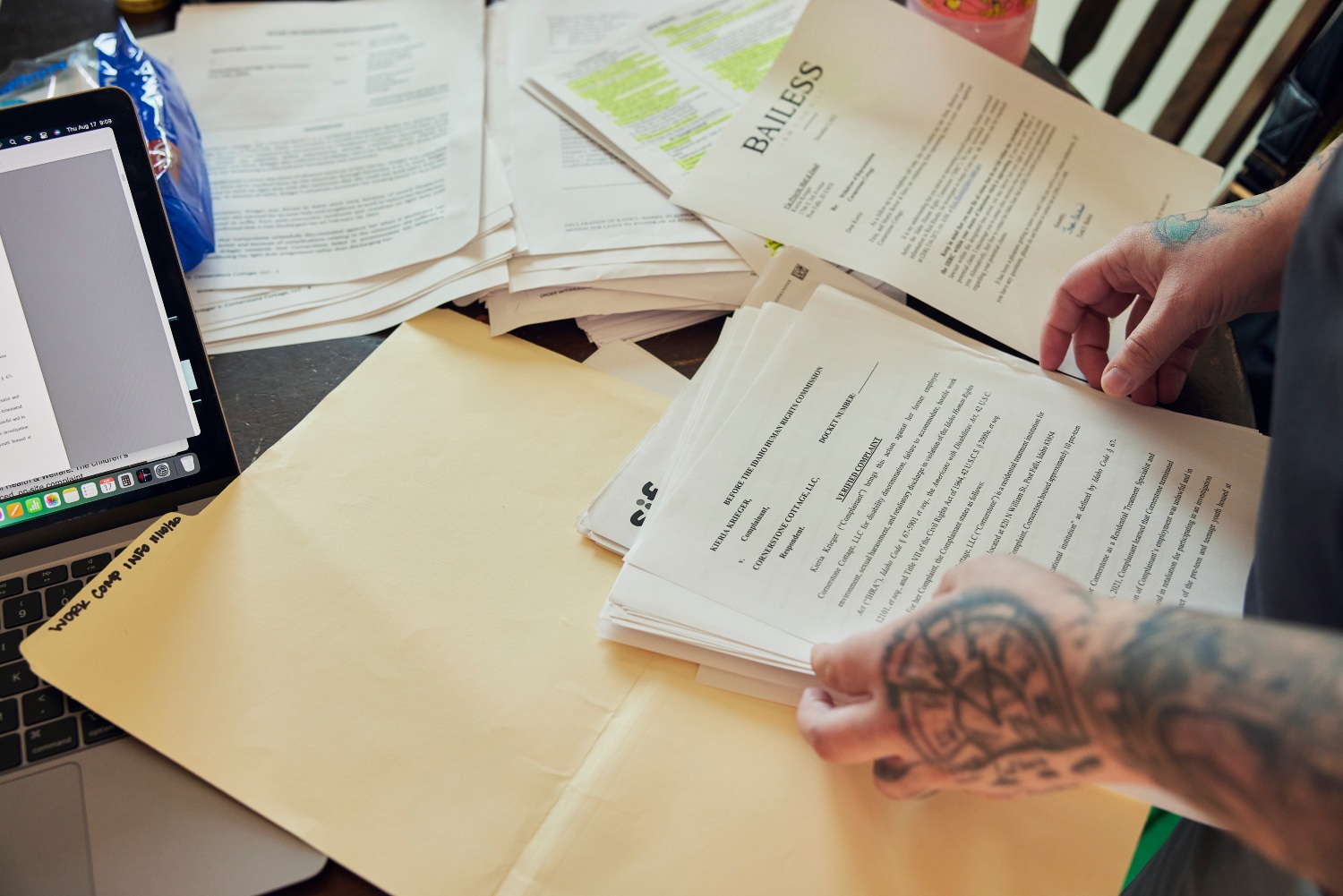

Emily Carter and Kieria Krieger now live together in Portland where their home is buried in documents from their yearslong fight. (Leah Nash/InvestigateWest)

But in Idaho, there’s a major gap in the law, said Megan Stokes, former executive director of the National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, an advocacy organization serving residential programs. Regulators visit annually to ensure the programs are in compliance with rules outlined by the state. But those visits are announced ahead of time, giving programs a chance to hide issues before inspectors come. Utah and Montana, by comparison, require multiple visits per year that include unannounced visits.

In Cornerstone’s case, Stokes would have major concerns. To say nothing of all the other rule violations at Cornerstone, Stokes said that if she found out that a facility hadn’t properly trained workers on restraint for years — as Idaho found at Cornerstone — they’d be booted from her organization.

“That scares the hell out of me,” Stokes said.

It’s unclear what it would take for Idaho to actually shut a program down, or even to suspend one. There’s no concrete guideline on how many licensing violations would trigger disciplinary action in Idaho. It’s up to state inspectors to determine “the provider’s willingness and ability to make the changes needed to be in compliance,” said Greg Stahl, a spokesperson for the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare in an email.

When asked about the sheer number of problems at Cornerstone, Stahl said that’s not necessarily taken into consideration when determining enforcement action.

“We also look at the scope and severity of a deficiency, not necessarily the total number,” Stahl said.

After receiving the complaint from Carter and the others, the state visited Cornerstone on Feb. 4, 2021, to investigate. When Carter went in to meet with investigators, she was optimistic that the state was finally stepping in. She felt Cornerstone needed to be shut down.

She’ll never forget what one of the state inspectors told her in the interview: Not only would Carter probably not have a job at Cornerstone after this, but Cornerstone wouldn’t be shut down, because there’s nowhere else to send kids like this. (The state worker who Carter claims said this declined to confirm or deny the statement when reached by InvestigateWest.)

That’s exactly what happened. None of the employees who filed the complaint worked another shift at Cornerstone after state regulators came that day. Carter and Krieger were fired. George and Hickey had already been on leave for personal reasons and never came back. A fifth signee had already left.

A month later, Carter received a letter notifying her that the state had broadly substantiated a majority of the complaint’s claims. Cornerstone received its own letter from the state banning new admissions. But neither public document references the most troubling, life-threatening incidents alleged by the employees, and most weren’t further investigated or referred to law enforcement.

Any idealism Carter held was shattered. She did everything right, she thought, and it didn’t seem to matter.

“I still had that inherent part of me that thought these systems are in place for good,” she said.

WHISTLEBLOWERS

Once they were fired, Carter and Krieger filed complaints with the Idaho Human Rights Commission, a state administrative law agency created by the Legislature. If nothing else, they thought at least one state agency could agree with a basic moral principle: That firing someone for reporting child abuse was wrong.

Because Cornerstone is privately owned, whistleblowers don’t have the same protections that they’d have if they were sounding alarms about a state-run agency. Idaho is an at-will state, and Smidt was right when he told Carter he was under no obligation to tell her why she was fired. There may be an exception allowing them to sue if they were fired in violation of a public policy, but even if they were to prevail, it’s unlikely they would win more than the cost of attorney fees.

Carter and Krieger thought they’d have a better chance with the Human Rights Commission. It investigates whether employees were fired in violation of federal anti-discrimination laws, such as reporting sexual harassment or sexual assault.

Once they were fired, Emily Carter, left, and Kieria Krieger filed a complaint with the Idaho Human Rights Commission, a state administrative law agency created by the Legislature.

They were optimistic. Smidt’s defense to the commission, records show, was that “we had no idea” who filed the complaint because it was anonymous and consequently, they couldn’t have been fired for retaliation. But the two former employees presented the commission with evidence indicating otherwise. They’d gathered screenshots of old text messages and spoke to former supervisors who admitted that management, including Smidt, knew who was behind the complaint within days.

In June of this year, however, Carter’s and Krieger’s claims for retaliatory discharge were denied. The Human Rights Commission decided that their claims didn’t fall under the scope of their powers. The reasoning: Their complaints to the state in 2021 focused on alleged sexual abuse of residents, and “not alleged discrimination toward employees.” In other words, the commission doesn’t protect the right of workers to report sexual assault of children.

Carter and Krieger couldn’t understand it. Is it really legal in Idaho to punish the people who report abuse or neglect?

“We’re not aware of any laws that pertain to this question,” Stahl, the state Health and Welfare spokesperson, told InvestigateWest.

‘NOTHING CHANGED’

Julianna Saltus worked at Cornerstone both before and after the state’s investigation in 2021. She wasn’t part of the complaint that triggered it.

She told InvestigateWest that her experience matched that of Carter, Krieger and the others, even after those employees were gone.

“Everything was the same,” said Saltus, a former treatment specialist at Cornerstone. “Nothing changed.”

Awful things kept happening to girls who went to Cornerstone, records show. One girl said she was grabbed by the throat and pushed against a tree by a staffer. Police continued to take suicidal and violent kids into custody, with one report noting it was because Cornerstone was “unable to control her.” The state in 2022 admonished Cornerstone for not taking a girl complaining of a headache and nausea to a hospital due to a concussion she suffered days earlier during a fight with another resident.

Abbigail Lord started working at Cornerstone in 2022, “eager to help” troubled teens like she once was, she said. Unlike earlier employees, Lord received the proper certification on restraint techniques. But it wasn’t nearly enough, she said.

“I wouldn’t say in any shape or form that we were trained on how to handle dangerous situations,” she said. (For his part, Smidt said even properly trained employees may feel that way.)

Lord worked there for a year. But she had no knowledge of any of the troubling incidents that occurred before she got there — nothing about the prior complaint investigation in 2021, nor about the girl raped in 2017.

Her issues with Cornerstone, however, mirror those raised by previous employees: She was discouraged from calling police for help. They were understaffed. She was told to report abuse or neglect to management, yet had no idea if those reports reached the proper authorities.

Cornerstone was supposed to be one of the few places able to care for these girls and keep them safe. But Lord found herself pleading with management to send the girls somewhere else that was better equipped to work with them.

“A few students needed more help than we could give them,” Lord said. “Something needed to be done.”

She asked management to at least give the kids more structure. Girls were running away simply to escape what was becoming a toxic environment, with fights and bullying. She warned that it was getting bad enough that a girl would get seriously hurt or worse.

She was right.

In April of this year, one of the girls, 14, ran away. She left because she wanted to avoid another fight with the other girls at Cornerstone, she later told police.

Post Falls police found her in a skatepark five days later. When she got back, she said that while she’d been gone, she ended up at a homeless encampment across the state border in Spokane. There, she said she was sexually assaulted by a man with green eyes and given drugs and money.

The same girl ran away two more times in the following months. She told another resident she was “going to Washington the long way” and that she would “sell her body to get rides and substances as well as money.”

The third time, two weeks went by with the girl missing. Finally, she called someone she knew from a gas station, saying she no longer wanted to live, that she couldn’t walk without passing out, and that she wanted to tell her family goodbye. Police scrambled to find her and took her to juvenile detention in early July.

It was one of the worst-case scenarios Lord feared. But Lord said Cornerstone management didn’t seem to take it seriously, which Smidt disputes. Other employees who shared her concerns quit out of frustration, Lord said. Weeks later, in August, she quit, too.

“We all felt the girls deserved better,” Lord said.

ANOTHER WORLD

Carter and Krieger lost contact for a while but reconnected around July 2022. Today, they live together in a townhome in Portland and are in a relationship sparked by their mission to expose Cornerstone.

“There was nobody else that cared like her,” Carter said of Krieger.

Their home is buried in documents from their yearslong fight, and they spend days digging through records, hoping someone with the power to enact change will hear them.

They say they aren’t fighting just because they want to shut Cornerstone Cottage down. It’s about creating a system where kids won’t be abused in programs like it in the first place. Carter now works for Unsilenced, a nonprofit working to combat child abuse in the troubled teen industry.

“It’s not the program’s fault that the system is designed to enable abuse and profit,” Carter said. “It just happens over and over. Survivors and media get burned out, then a kid dies, and the program chooses to close. A year later, all the staff are working at other programs.”

Emily Carter and Kieria Krieger are in a relationship sparked by their mission to expose Cornerstone. (Leah Nash/InvestigateWest)

The Idaho Human Rights Commission’s ruling against them was deflating. Not just because they didn’t prevail, but because even the commission presented a sanitized version of all the problems at Cornerstone.

But in August, Carter and Krieger got a glimpse at what it would look like if things were different.

When Krieger asked for a copy of the Human Rights Commission ruling, the state sent it to her. But they accidentally also sent a copy of an earlier draft, later telling InvestigateWest that such drafts should be destroyed.

In that draft, the state said that Krieger was unlawfully retaliated against, because “both Carter and Krieger reasonably believed that some of the conduct about which they were concerned was unlawful under anti-discrimination statutes,” it said.

And one sentence captured what Carter and Krieger have been saying for years, as much as an official state document could. It was what they’ve fought the state to acknowledge and act on:

“The preponderance of the evidence indicates a tumultuous and dangerous environment, both for staff who suffer serious injuries and for at-risk youth who become violent and suicidal.”

In the final version, it was gone.

FEATURED IMAGE: Cornerstone Cottage opened in 2016 in Post Falls, Idaho, a booming bedroom community 25 miles east of Spokane. (Erick Doxey/InvestigateWest)

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Reach reporter Wilson Criscione at wilson@invw.org. This report was supported in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the frequency of police calls to Boise Girls Academy.

Help Us Learn More: InvestigateWest plans to keep investigating Idaho youth residential facilities. If you have information to share, please contact reporter Wilson Criscione at wilson@invw.org. You can also message us on Signal at 509-999-8885. If you have documentation, you can share files using this Dropbox link: https://www.dropbox.com/request/h6jg572xAi75GU89SRho