Seattle’s biggest industrial soot producer is seeking a lease renewal on county-owned land beside a heavily polluted south Seattle neighborhood with a large population of people of color and a documented history of air and water quality problems.

It’s a neighborhood where, according to a health study, residents live sicker and die younger than people in whiter and more affluent parts of Seattle, in part because of high pollution levels.

It’s a neighborhood where, according to a health study, residents live sicker and die younger than people in whiter and more affluent parts of Seattle, in part because of high pollution levels.

Government records show that the glass recycling plant operated by the multinational Ardagh Group near the base of the Highway 99 bridge over the Duwamish River is by far the most prolific single emitter of soot in the Puget Sound region. It sits beside Georgetown and South Park, two neighborhoods with some of Seattle’s biggest concentrations of minorities. Studies have identified it as an area with one of the highest asthma hospitalization rates in King County.

The company in 2016 fought off regulators’ efforts to tighten air-pollution limits on the facility. And in recent years the plant has been cited for exceeding water-pollution limits. However, if the lease is renewed, Ardagh says, it will plow $25 million into environmental improvements at the plant.

Despite that environmental history, the decision the King County Council will make regarding renewing the lease will not be easy. The company employs 340 people, including about 300 hourly employees — half of them people of color — in relatively well-paid union jobs.

Not only that, the company recycles all of King County’s glass waste, cranking out about 1 million bottles a day. If you’ve drunk wine produced in Washington, you’ve almost certainly used Ardagh’s product. There is only one other such glass recycling facility in Washington, and because of the shortage of glass-recycling capacity, many local governments around the state have simply given up on it. Without Ardagh, King County residents might well have to send 465 tons of glass per day to an Oregon landfill.

To complicate the situation, even the international trade war and global warming loom large in this decision. The company asserts that it has already lost market share to Chinese competitors and predicts that without its bottles, Washington wine makers would likely turn to China. Those bottles would have to be shipped across the Pacific, causing greenhouse gas emissions.

Flyers encouraging community members to attend the Oct. 8 meeting about the lease renewal. (Photo/Change.org)

When Georgetown Community Council member Clint Berquist learned of the company’s efforts to win a new lease, he launched an online petition drive in opposition that has garnered more than 500 signatures.

“The people who are going to be footing the bill for the health impacts of this don’t even have any idea that this is going on,” Berquist said in an interview. “There’s been no outreach to the community whatsoever.”

The glass plant is in the district of King County Council Member Joe McDermott. McDermott said the council will be looking for a recommendation that will come from one King County staffer: Anthony Wright, director of the Facilities Management Division.

Wright turned down repeated requests for an interview for this story. He is now scheduled to meet with community members Oct. 8 at South Seattle College’s Georgetown campus.

Company says it is reducing pollution

The company says it is doing everything it is supposed to under government pollution permits, including working to correct exceedances of water-pollution limits.

“We care about our neighbors,” said Joshua Markus, Ardagh’s general counsel for North America.

Markus emphasized in an interview that the company is working hard to improve its environmental performance. The company says it already has invested $3.5 million in technology to reduce emissions from one of its furnaces; to run a street sweeper for eight hours a day to reduce pollutants running off into the Duwamish River; and to hire a full-time environmental engineer, one of only two such positions assigned to a single plant in the multinational company’s 13 North American plants, according to Ardagh.

Even though Ardagh tops the list of industrial soot producers in the region, Markus argues that the plant’s contribution to air pollution in south Seattle pales in comparison to two non-industrial sources of soot: vehicles, including cars and trucks; and residents burning wood in fireplaces and wood stoves in winter to keep warm.

Those are definitely major air pollution sources in the south Seattle. The area is crisscrossed by major highways and arterial streets frequented by trucks serving the nearby Port of Seattle, many of which are older diesel models that are notoriously dirty. And the neighborhood is a hot spot for people who burn wood, because that’s a cheap way to keep warm.

The company and its predecessors have been at the same location for more than 50 years, Markus noted, and Ardagh was unhappy when the county, instead of renewing the lease, decided to seek bids from other companies interested in using the property.

“This is very unfair treatment and (we) don’t understand the county’s desire to replace us as a tenant,” Markus said, adding that such a move “would have many negative attributes, whether it be environmental, certainly on jobs, certainly on the recycling system of King County and the city of Seattle.”

The county’s public notice that the land is for lease envisioned a warehouse as an alternative to a glass plant. Ardagh said in a document submitted to county officials that those jobs would pay perhaps $16 per hour versus the $28 per hour earned by Ardagh employees. Ardagh’s union employees receive benefits that translate into an average compensation package of about $90,000 per year, company spokeswoman Katie Skipper said, explaining that the figure includes “a pension, 401(k) and a generous health care plan, along with vacation and holiday pay. The average annual compensation for union employees, including wages and benefits is $90,000 and, of that amount, approximately 8% is payroll taxes.” That 8% payroll tax is not paid to employees, though.

Ardagh Group’s glass recycling plant is located near the base of the Highway 99 bridge over the Duwamish River, amid some of south Seattle’s busiest roads. The company argues that its air pollution pales in comparison to the soot emitted by cars, trucks and other vehicles, as well as residents who burn wood to keep warm in cold weather. (Matt M. McKnight/Crosscut)

Operating 24 hours a day for 365 days per year, the glass recycling plant in 2018 released 161 tons of soot, known in the environmental regulation field as “fine particulate matter,” into the air, according to records of the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency. In fact, in 2018, government records show that Ardagh emitted more soot than the next six largest emitters in the region put together.

Ardagh is also the region’s largest source of sulfur dioxide pollution, the Clean Air Agency’s records show. That chemical makes breathing difficult for asthmatics and can cause wheezing, shortness of breath and chest tightness. The company has not been cited for discharging this pollution because its emissions are under the limits specified in its government-issued permit.

The Clean Air Agency’s data also show that the plant regionally is the second largest emitter of nitrogen oxides, the third largest polluter of a class of compounds called toxic air contaminants, and within the top 10 emitters of carbon monoxide, hazardous air pollutants, and volatile organic compounds, although those pollutants are not regulated under the facility’s government-issued permit because the levels emitted are considered too small to be regulated.

A document provided by the company to King County and obtained by InvestigateWest under the Washington Public Records Act shows that the company has had several run-ins with governmental environmental agencies in the last few years.

The document reveals that the company has been in trouble with the state Ecology Department as recently as November 2018, when state inspectors cited the firm for four violations of rules regulating how much toxic zinc and copper and how much turbidity are allowed in rainwater draining off the property into the Duwamish River.

Markus said the company takes stormwater runoff regulations “very seriously.”

“We have had some challenges with runoff, and we’ve been working with the state Department of Ecology to correct” the violations, Markus said. “I’m happy to report the effort is paying off.” The state granted the company a one-year extension until September, 2020, to design and install a stormwater treatment system to control the problem. In the meantime the company is using a street sweeper to keep pollutants out of rainwater runoff.

Within the last three years and three months, the company violated state limits four times in wastewater it dumped into the Duwamish River, according to a document submitted to the county by the company in June 2019. The company said malfunctioning equipment caused three violations, and the fourth was caused by a leak, all of which were corrected.

As for air pollution, Ardagh in recent years earned violation notices for at least four infractions involving failing to test its emissions, failing to submit test results, and failing emissions tests it did conduct, according to the document the company submitted to King County in June. Those all occurred within the last three years and three months.

The company earlier this year closed the most pollution-prone of the five furnaces at the plant. In the document filed with King County, the company said it shut down the offending furnace “as a result of lower demand due to foreign imports.” In the interview with InvestigateWest, Markus, the company’s lawyer, said, “This was a very difficult decision for us because it directly resulted in the loss of about 50 jobs.”

Ardagh is seeking to renew a lease on 17 riverside acres that is across the street west of the main Ardagh plant on East Marginal Way South.

Rainwater runoff pools at Ardagh Group’s south Seattle glass recycling center. The plant was cited late last year by state Ecology Department inspectors for failing to control pollutants in the runoff, some of which enters the Duwamish River. The company is currently working to design and install controls on the pollution. (Matt M. McKnight/Crosscut)

It’s unclear whether Ardagh’s bid to renew its lease on these 17 acres along the Duwamish River would pay King County as much as competing companies that would operate a warehouse there. That’s because state law exempts other companies’ bids, like Ardagh’s, from the Public Records Act, until one company is declared the apparent winner in the bidding contest. The county has not disclosed the other bidders and so it is not yet known how many jobs and what kind of wages Ardagh’s competitors are offering.

Once a company is declared the apparent winner of the bidding process is the public allowed to learn the name of that company and the bid price, and see how much each bidding company would’ve been willing to pay to lease the land.

The 17 acres the company leases from the county represents only a portion of Ardagh’s operation, the strip of land between the main plant and the river. On that strip of land are two companies that are sub-tenants of Ardagh that handle incoming glass and provide lime for the production process. Replacing that with a warehouse would mean additional truck traffic in the area, Ardagh argues, including big rigs trying to make challenging right-hand turns off already-crowded East Marginal Way South.

Unions representing Ardagh’s workers are lobbying to keep the plant alive.

“If our plant is forced to close because of an incoming warehouse, our jobs would be replaced by low-wage jobs with high turnover rates,” said a letter to county officials by members of the United Steelworkers, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. It was signed by more than 175 workers.

The plant is located in one of Seattle’s most industrialized districts, one that has been a center of manufacturing since early last century. That left widespread environmental contamination. In fact, the Duwamish River, immediately adjacent to the plant, is undergoing a major cleanup in the federal Superfund program.

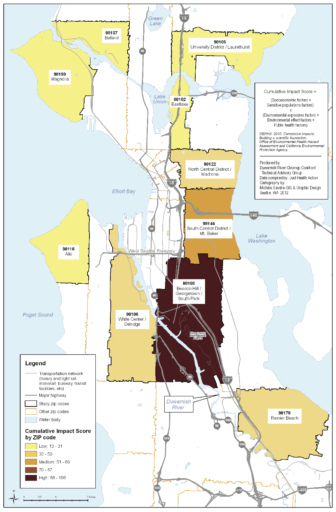

In this map from the report showing cumulative impact score by Zip Code, a darker color indicates a higher score.

Preparations for the Superfund cleanup included a study establishing that in the 98108 ZIP code adjacent to the Ardagh plant, which includes the neighborhoods of Georgetown and South Park, has the highest “cumulative impact score” of 10 ZIP codes studied when it comes to negative socioeconomic, environmental and public health characteristics.

On air pollution, the neighborhood came in second below Eastlake, which sits right below Interstate 5.

The study was spearheaded by the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition, a nonprofit coalition of environmentalists, neighborhood groups, local businesses and the Duwamish Indian Tribe that was officially designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as a “Technical Advisory Group” to give the community a say in the Superfund cleanup.

Company pledges environmental improvements

As part of its bid to renew its lease, Ardagh is pledging to spend some $10 million on technology to lower emissions and $15 million to rebuild a furnace to reduce pollution.

That’s a far cry from a few years ago, when the company strenuously objected to new air-pollution limits ordered by the Clean Air Agency on two of its five furnaces. Those would have been the strictest air-pollution standards on any glass plant in the country.

The company took the agency to the state’s Pollution Control Hearings Board, where the air pollution agency asked: If the pollution-control technologies are cost-effective for other glass foundries around the country, why not here?

Retrofitted with the new technology, the old furnaces would have seen a 60% reduction in particulate matter emission. Ardagh hired two consulting firms that argued that the technology either wouldn’t work or was too expensive. The board ruled against the Clean Air Agency and allowed Ardagh to continue operating under one pollution limit set in 1994.

The company’s lawyers cited what they called serious underestimates by the agency about costs for retrofitting two of the plant’s five foundries.

For example, the Pollution Control Board said in its ruling, the Clean Air Agency said reducing air pollution from the facility would cost $2,373 in demolition costs, when the actual cost estimated by a consulting firm hired by the company was $253,875.

During the pollution board’s 2016 hearings, the Clean Air Agency said measurements of the soot pollution at a monitor about three-quarters of a mile from the plant – part of a 55-station monitoring statewide network – showed the highest soot pollution levels anywhere in the state. South Seattle is one of 17 areas in the state being closely monitored for soot pollution by the Washington Department of Ecology.

In the end the Clean Air Agency lost because it had not calculated an economic cost-benefit analysis for two technologies that the company agreed would have reduced pollution.

King County official to decide

Anthony Wright has served as King County’s Director of Facilities Management since 2014.(Photo/LinkedIn)

For now, all eyes are on what Anthony Wright of the King County Facilities Management Division will decide. Although Wright refused an interview for this story, his office emailed a statement that broadly outlines the criteria for evaluating proposals, stating that the county is looking for “job creation and retention potential, environmental impact of proposed lease uses, tenant investment in the property, and rental revenue potential.”

Like Berquist of the Georgetown Community Council, the head of the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition/Technical Advisory Group took issue with the characterization by the company’s lawyer that Ardagh is concerned about its neighbors.

“Because that company really has not interacted at all with the community over all their years of violations, this is what happens: The community gets their back up and they want to do something,” said James Rasmussen, Superfund manager for the cleanup coalition.

Rasmussen learned from an InvestigateWest reporter of the company’s proposal to spend $25 million upgrading pollution-control systems at the plant.

“God bless them if they mean that,” Rasmussen said. “If they really mean that, they should be at the meeting and tell the community.”

Belinda Littlefield contributed to this report.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at https://www.invw.org/newsletters/.

Corrections: This story has been altered from its original form. It was changed to reflect James Rasmussen’s updated title. Also, it originally said the plant emits nitrous oxide; it actually emits nitrogen oxides. Also, the story originally said the plant emits carbon monoxide, hazardous air pollutants and volatile organic compounds at levels below those specified in its government-issued air pollution permit. However, in fact, the facility’s air-pollution permit does not set any limits because the levels emitted are below what would be required under the law for a limit to be set. Based on a statement by a company attorney, the story originally said Ardagh has a full-time environmental engineer assigned to two facilities in its 100-unit, 22-country network; in fact, there are two plants out of Ardagh’s 13 North American glass plants that have full-time environmental engineers.