One day before Oregon’s usual Valentine’s Day statehood celebration this year, the Capitol was awash with reporters chasing a rare story on the abuse of access to power rather than the frosted sheet cake being handed out by the Oregon Wheat Growers League to mark the state’s 156th birthday.

In a state where ethical behavior is assumed rather than regulated, former Gov. John Kitzhaber offered his resignation in a pre-recorded speech heard in his reception room, while de facto-governor Kate Brown prepared for duty in the secretary of state’s office a floor below.

Kitzhaber was being investigated following media reports that his fiancé, a consultant, was selling access to the governor’s office and using state resources for personal gain, and that he blurred the line between his job as governor and his re-election campaign.

For many in the state, Kitzhaber’s resignation is a thing of the past. But the scandal that ensnared the former governor highlighted a wobbly legal framework in Oregon’s government, where good behavior is taken for granted rather than enforced.

That framework explains why Oregon fared poorly in this year’s State Integrity Investigation, earning an overall score of 58 – an F grade – and placing 44th among the 50 states in the data-driven assessment of state government accountability and transparency by the Center for Public Integrity and Global Integrity.

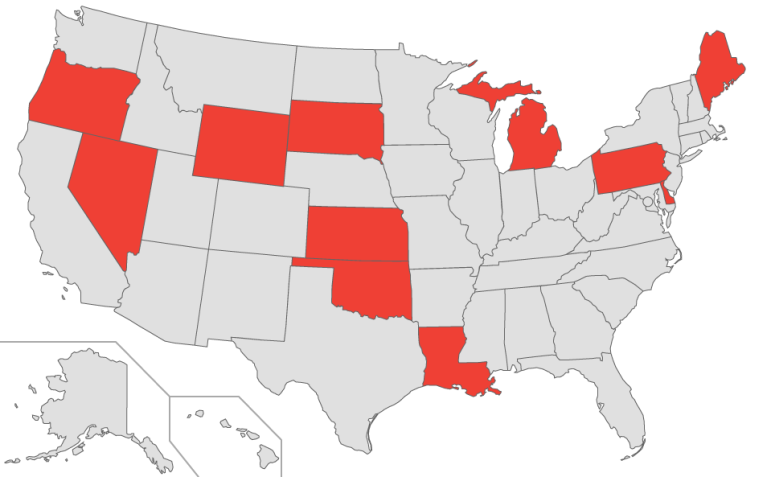

Oregon is one of 11 states to receive an F on a national good governance scorecard.

“It’s not like Chicago or something,” said Dan Lucas, a researcher, policy advocate and chief editor of the blog Oregon Catalyst. Noting four of the last seven Illinois governors went to jail, he said, “We don’t have that level of corruption.”

But Oregon’s relative lack of scandal may be a function more of good manners rather than of law. As Lucas and others note, and this year’s failing grade suggests, lines are easily blurred in Oregon government, and ethical lapses and partisan abuses of power – while often not criminal – have been smoothed over by both political maneuvering and etiquette.

Kitzhaber’s resignation caused Oregon to receive an F in the category of executive accountability. The debacle also ensnared the Oregon Government Ethics Commission, and highlighted why Oregon is one of the worst performing states with regard to access to information (F).

Oregon’s overall failing grade represented a substantial dip from the C- the state received from the last State Integrity Investigation scorecard in 2012, but the grades and scores are not directly comparable due to changes made to improve and update the questions and methodology—like eliminating the category for redistricting, a process that generally occurs only once every 10 years.

Ethics Commission missteps

Oregon’s ethics commission didn’t move quickly to investigate complaints regarding Kitzhaber, and more importantly, his fiancé Cylvia Hayes. At the time, officials said they struggled with whether she was covered by state ethics law.

But the law is clear – Hayes, as a member of Kitzhaber’s household, was subject to the rules. Yet – until ethics reform passed the legislature afterward – the ethics commission was unprotected from political interference by the governor’s office. The governor either appointed its directors, or gave names to the Democratic-controlled legislature for nomination by party leaders, one possible explanation why the commission didn’t act. Even after reforms, Oregon’s ethics commission still lacks budget protections, the authority to independently investigate bad behavior, and the staffing and technical support to see its mission through.

The commission’s lack of rigor hurt most every other category of this assessment.

As the keeper of records designed to collect robust information about the state’s elected officials and civil servants, the commission never audits the asset-disclosure forms it collects, the State Integrity Investigation revealed. Enforcement has been so lax that political leaders have been able to fudge on specifics in their disclosure forms or simply fail to provide significant information. The forms aren’t available online so that members of the public can check. And the State Integrity probe discovered that people who examine the forms universally report that the quality of information is substandard.

Holes in public records law

Such issues underscore why Oregon remains one of the worst performing states regarding access to information (an F grade), ranking 34th even in a category where only six states earned a passing grade. The state has no open data laws or independent agency charged with overseeing citizen access to government. Oregon’s Public Records Law is also full of exemptions – at least 480 – and lacks firm deadlines for delivery of public records. The Kitzhaber debacle underscored the consequences when public information doesn’t flow freely or in a timely way; substantive deadlines might have allowed voters a closer look at Kitzhaber’s issues before he was re-elected, only to resign a month after his swearing-in.

Oregon’s lawmakers (D- in legislative accountability), like the ethics commission, operate without legal safeguards against unethical conduct. The state legislature still does not have laws prohibiting nepotism and cronyism in hiring, for example – a situation intended to allow rural legislators to support a family in the state capital of Salem but that leaves the government vulnerable to abuse. And low pay combines with a lack of campaign finance law to eliminate a buffer between Oregon legislators and special interests in the private sector.

As a result, legislators can grow accustomed to practices that cut corners. They may fudge the lines between their part-time legislative duties and their other jobs, angle for work in places where they shouldn’t or find themselves enormously dependent on campaign contributors as state races get more expensive.

“The problem in our legislature regarding integrity is not about the ethics stuff. Or going to jail. These are intellectual integrity issues…” said Phil Keisling, Director of the Center for Public Service of the Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University.

Few requirements for judges, courts

The judiciary branch is also plagued by potential for conflict and a lack of legal safeguards; the category grade for judicial accountability is F. While, again, Oregon judges don’t seem to have overt corruption issues– judges weren’t sanctioned for bad behavior at any point during the study period – staffing shortages prevented many state-level judges from offering full opinions on their rulings. And Oregon lacks laws to force its judges to explain their decisions to the public. The state also lacks judicial performance evaluations, and is behind other states in making court data publicly available. Unless a complaint is filed, the Oregon Commission on Judicial Fitness lacks the power to investigate problems, and even then, those records are sealed unless they lead to discipline.

There were some bright spots: the state’s budgeting process earned a C and the secretary of state’s audits division a C+. Both were sufficiently staffed, transparent, and had the authority to act with independence, suffering only from the same lack of legal safeguards that brought state scores down overall.

And while Oregon’s civil service system scored only a 66 – a D grade – that ranked the state 12th, the highest of all its category rankings. Government workers aren’t always protected from political interference in Oregon, but the civil service system in the Beaver State does seem to be better than most.

Do you still have to pay big bucks to see those asset-disclosure forms?

Hi Cass, the answer is: it depends. You can often get one or two asset disclosure forms via email at no cost, but to examine sets, or a several years’ disclosures made by one filer, there are associated research fees. Stay tuned, we’ll be tackling more on asset disclosure in an upcoming Redacted. https://www.invw.org/series/redacted/