Justin and Julieth Buri were about to lose. Again.

This time it was a gold-colored bungalow, a 1,382-square-foot house on Northeast Fremont belonging to the estate of Veona Monroe, a church devotee and the matriarch of a large Portland family.

It needed work, but they were smitten, if not optimistic. Justin Buri, by day an advocate for tenants, knew well the scarcity of Portland houses. They offered $250,000 — $10,000 over the asking price — and crossed their fingers. This time it took a full day before another buyer outbid them, paying all cash. Seven months later, the house sold again, remodeled, for $483,000.

“It was a nightmare,” Justin Buri said of their house-hunting days. From the time those days began in October 2013 until they ended the following May, the Buris were outbid 16 times for homes, many times by all-cash offers.

“Sometimes we wouldn’t even get beat by that much, but because it was a cash offer, the owner would prefer it,” he said.

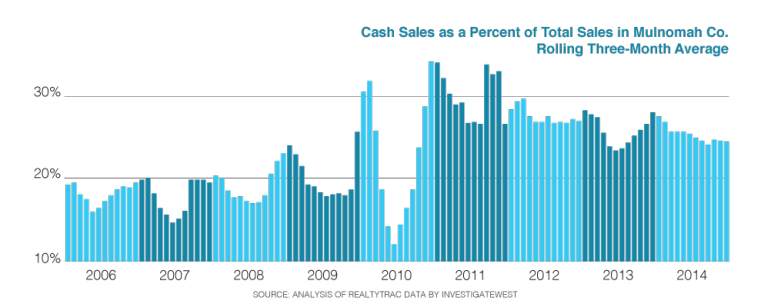

So goes the story. Cash is king in red-hot Portland real estate, representing a full one-third of single-family home sales last year. Depending on which urban myth you subscribe to, many first-time home buyers are just out of luck either because the Metro-area urban growth boundary makes housing scarce and pricey, or because Portland is so great, housing is being gobbled up by a flood of New Yorkers and Californians racing here for a slice of nirvana. It’s a post-Portlandia feeding frenzy, right?

Well, no. Not entirely.

Investors ♥ Portland (Or why it’s so hard to buy a house here)

Like many cities, Portland is facing pent-up demand by buyers who hunkered down through the recession. Limited supply, new residents, and uncertain sellers are also strong market factors.

But an InvestigateWest analysis shows Portland’s affordability is also being pressured by investors so bullish on this city’s single-family housing they’ve bought properties by the dozen on the heels of the recession, driving up prices and rents as they go.

Traditional real estate investors — flippers, remodelers and developers, companies that to some extent have always been here — have been joined by hundreds of private investors and new private equity firms out to make money for investors through real estate.

GRAPHIC: More than 17,000 listed homes in Multnomah County have sold for cash since 2006

The increasing pressure of these buyers in the traditional real-estate market after the Great Recession’s foreclosure sales dried up has helped to distort the Portland real estate market, bidding up prices and making it more difficult for would-be homeowners like the Buris. Once the American dream, home ownership is increasingly a securitized asset that is outside the reach of ordinary Portlanders.

One company, American Homes 4 Rent, exemplifies the trend. The company purchased significant portions of property in communities hit hard by foreclosure before coming to Oregon in 2013. It has since sold hundreds of millions of dollars in bonds to investors, backed by single-family rentals. Other companies designed to generate profits for investors involved include Equity West Capital Partners, a California-based private equity firm that has purchased dozens of Portland-area homes to flip. Dilusso Homes and Portland Development Group, both local remodelers and developers, similarly take cash from private investors in exchange for returns on their deals.

In the greater Portland area (Portland, Vancouver and Beaverton), such institutional investors — buyers of more than 10 single-family homes for cash — bought 6,103 properties between 2011 and the end of 2014, according to data from the real estate information company RealtyTrac. That was nearly 14 percent of all cash sales in the area. And as foreclosures slow, those investors have started to move in on the traditional housing marketplace to compete with the likes of the Buris. The InvestigateWest analysis found 26 institutional investors competed regularly in the listed marketplace, where people in search of their own home typically shop. There is nothing illegal or untoward about that activity — it’s just a new way of doing business.

In a few short years, the promise of high returns has also pulled in droves of ordinary people who are increasingly shifting their wealth from traditional banking and investment tools and into housing or pooled-asset real estate.

Not all of these are the nouveau riche, or even old money. Many simply reflect a national flight away from 401ks, savings accounts, and other products amid deep distrust of banks and Wall Street. Such investors buy their own properties to rent or remodel. Or they can now choose from a bevy of new investment firms to drop their money into Portland housing.

In a December analysis, RealtyTrac ranked Portland second among cities nationwide where institutional investors were active in terms of the size of the potential returns to be made by those investors.

As investment tightens markets and helps to drive up prices, and redevelopment replaces the city’s most affordable dwellings, the city’s Housing Bureau has convened a Community Oversight Committee, in part to oversee strategies to lessen gentrification’s impacts in North and Northeast Portland. Its chairman is Bishop Steven Holt of the International Fellowship Family church, which was displaced from Northeast Portland during the crisis. He points to new home prices of up to $600,000 and wonders aloud who can afford to foot the bill.

“It isn’t the people who are beginning their careers. It isn’t the people who are in the early stages or even in middle-income stages. It is the folks who are upper-income or upper middle-class income that can afford to buy these houses. So you’ve just classed out a significant amount of people,” he said. “Our city is becoming an exclusive kind of rich kid club.” Grace Widdicombe, president of the Northwest Real Estate Investors Association, says among those who have turned to real estate are people trying to climb out of financial holes.

“Some people were actually retired and all of a sudden they lost half their retirement fund in their IRA. I hear a lot of that,” she said.

Others have simply learned they can’t make money on bank products anymore. She points to savings accounts, certificates of deposit, and managed funds as unproductive for people trying to plan financial futures.

As real estate holds promise for those who want their money to make money, the force of investment is a growing factor in setting prices for the rest of the buyers. And what’s making housing prices skyrocket isn’t just that investors are here tightening the housing supply with cash. It’s how traditional buyers are responding: by trying to look just like them, setting the safeguards of traditional financing aside.

“Anytime you have multiple offers and you have cash in the mix, the conventionally financed borrower is going to try as hard as they can to look like a cash buyer, even though they’re still being financed,” said Eric Hagstette, owner and principal broker at Inhabit Portland, a real estate company.

When sellers have a choice, they prefer the sure thing. Unlike cash, financing can fall through, especially in a market with tighter credit. Buyers who turn up with a check rather than a pre-approved loan are more likely to complete the transaction –and sellers know it.

To compete, some buyers are simply borrowing cash from friends and family and financing their houses after closing — bout 14 percent of cash buyers in the greater Portland area between 2011 and the end of 2014, in fact, according to RealtyTrac.

Others are overbidding to ram deals through quickly, then waiving the right to negotiate price if an appraiser doesn’t agree. The practice comes with significant risks. It also allows the next guy to price his house just as high, while one sale becomes a benchmark for the starting price of the next, Hagstette said.

“The ultimate effect is it’s taking away any sort of price cap,” said Hagstette. Our marketplace? “In a sense, it is unregulated by appraisers.”

While larger investment firms did not respond to InvestigateWest’s requests for comment, some smaller investors shared how the rising prices and competition for houses are changing their work.

Alicia Liberty, who owns Liberty NW Homes, said rising prices have forced her firm to broaden its vision, for example adding a second story to a home to make its investments pencil out.

John Reilly, of Reilly Signature Homes, said banks are again starting to talk about loaning money to his company, which has been using private capital to remodel derelict rentals and other homes he described as in total disrepair. The company has remodeled about 50 homes in eight years, Reilly said.

Across much of Portland, prices seem high, said Steve Wilson, a former project manager for multifamily remodels who has flipped homes through Big Moose Development since launching the company during the crisis.

Perhaps ominously, Wilson says he feels an echo of 2006 in today’s marketplace: Buyers are overpaying. Sellers want top dollar for houses that need work. And developers and remodelers are pushing prices up to $600,000 to make profits.

“I think they’re pushing it to where we’re going to have another crash,” Wilson said.

Big cash moves into the MLS-listed market as auctions fall.

One quarter of the overall market is cornered by cash buyers.

The torture formula — less stock, more buyers, lots of cash

In a market where multiple offers are raising prices, Teri Toombs, Principal Broker at Living Room Realty, says she discourages people from overpaying for homes. But some can’t resist. Some people don’t want to continue renting. And they don’t care what that costs.

An in-house poll led by Toombs’ colleague Alyssa Isenstein Krueger, Living Room found more than a few first-time buyers with cash to throw around. The Living Room agents that responded said that of 148 first-time buyers served in 2014, 42 percent came to the table with funds from friends and relatives to help grab whatever edge they could leverage. The sums ranged from up to $470,000. It’s not scientific, but it suggests a hard new reality in the market.

For those without cash? Those that can’t overpay?

“It’s torture. And I try my best to prepare them for what they’re in for and I see them starting to glaze over like, ‘Why is this lady saying all this? Why can’t we just start looking at houses? Why is she bringing us down like this?’” said Toombs. “With determination and being really diligent about it, they can get into a house. But they have to realize that they’re going to be moving into emerging neighborhoods.”

The inner city neighborhoods and those areas with the cute bungalows and post-war homes that typify Portland are out of reach for most first-time buyers.

Here’s part of what has changed: Back in 2008, when shaky mortgages had been toppling for a year and banks were frantically dumping foreclosed homes, investment buyers and their agents could be found near daily on the steps of the Multnomah County Courthouse, or any other courthouse in the region. This was the place for crowding around auctioneers, bidding on single-family homes, and buying up properties by the dozen.

These days, however, the foreclosure scene has tapered off. Many mornings at the courthouse an auctioneer is still there, still standing on the marble steps, a handful of clipboards on the radiator. But the pickings are slimmer. One or two or three houses at a time. And the auctions are often canceled, title problems or other glitches ensnaring the last trickle of real estate on which an army of investors have now come to depend. Oregon is also moving more foreclosures through the courts.

A handful of the actors who most frequently buy at auction — Bulldog Capital Partners of Lake Oswego, Caliber Real Estate of Bellevue, Wash., and Vestus, the Northwest’s largest foreclosure investment group, among others — are still there. But the market has thinned. “There is no inventory right now. That’s the bottom line. There is not enough to go around,” said Jeremy Romig, a local Vestus representative.

As private and institutional investors step away from the foreclosure market, they are shifting into private deals as well as onto the MLS, where they compete directly with traditionally financed homebuyers. In most cases, they’re looking at the lowest cost housing on the market, and competing with first-time buyers like the Buris.

A home in the Woodstock area of Portland that was just put on the market is inundated with real estate agents’ cards.

Flips, remodels, redevelopment and new rentals

Data on how such buyers affect the listed market are difficult to corral. But an InvestigateWest analysis of roughly 12,000 buyers who paid cash for listed homes in Multnomah County between 2006 and 2014 found more than 850 individuals or their corporate doppelgangers buying between two and nine homes. Those buyers were joined by the 26 institutional investors that captured hundreds more.

Translation?

Among the approximately 12,000 purchases, there were at least 2,750 flips, remodels, redevelopments and new rental acquisitions in place of new homeowners at the lowest price point of the market. Owing to the lack of transparency in real estate holdings — many homes were acquired by opaquely named corporations, and some buyers use several at a time — and to the tendency of equity groups to place houses in the names of their investors rather than of the investment company, that number is likely much higher.

There is, perhaps, no place in which the shift has been captured better than at the DoubleTree Hotel near the Lloyd Center. This is where investors converged April 2 for the 2015 Vendor Fair hosted by the Northwest Real Estate Investors Association, in a white box of a room with fluorescent lights where vendors told a tale of emerging trends.

Companies like Lake Oswego’s Beutler Exchange Group, which holds investor money between flips to defer taxes, were in the mix. Several others offered self-directed IRAs, which, in addition to the standard tax benefits, can be used to access non-traditional assets like real estate and notes. There were hard-money lenders, offering cash for quick flips at 12 percent interest rates and varying points. Alpine Mortgage Planning was represented for its construction loans, which some investors use to repackage their debt once they hit the Fannie Mae limit of 10 mortgages, opening up borrowing for more.

Tenant screening services, inspection companies, insurance and title companies — all were advertising. And the browsers were not your Wall Street types. They were regular people of all races and every age, wearing clothes as varied as leather, jeans and sport jackets, some toting kids, others sporting purple hair, giving even this event its Portland flare.

Some version of this scene repeats itself almost every week in Portland, at meetings and workshops designed to help people build wealth this way, and to make the most of flips and rentals. The post-crisis marketplace is full of investor-friendly tools. They are tools that have combined with limited supply and tight credit to tilt the market in favor of all-cash bids.

A ‘Fair Shot’ or not?

For some companies and investors, it’s all a bit of financial fun. Castle Partners, L.P., a pooled investment vehicle registered in Delaware, bought properties through its Oregon affiliate Castle Advisors using several companies with variations on the name COTD, an apparent play on the seafood menu phrase “Catch Of The Day.” One real estate developer held property in a company called Boondoggle LLC. Another bought six houses with My Financial Workout.

For Justin Buri, who is executive director at Community Alliance of Tenants, buying in this market meant pushing past his unease with its burgeoning equity issues. It’s not his style to troll neighborhoods talking about which are about to “pop” with fresh waves of gentrification. While viewing his own prospective homes, he watched real estate agents wave off nearby properties — other people’s homes — with assurances they would be torn down. It fit him like a shoe on a doorknob.

“Being a player in that was really challenging for me,” he said.

But his own need for stability egged him on. He can now tell his story in the rowhouse he and Julieth Buri own, a St. Johns property with an abundance of natural light, bursts of bright color, and flashes of art-savvy décor. The couple were able to buy the home after deciding to look farther from more popular areas.

Through their own struggles — they were displaced renters before they were homebuyers — Justin Buri also watched the Community Alliance of Tenants shift focus from keeping rentals up to snuff to helping tenants stave off eviction and rent increases as the real estate market amped up.

Justin Buri at his home in the St. Johns neighborhood on a recent April evening. Buri has seen firsthand the pressures of a changing housing market at his job with the Community Alliance of Tenants.

Sarah Edelman, a senior policy analyst on the Housing Finance and Policy team at the Center for American Progress, a D.C. think tank that has studied equity ownership of single-family homes, says policymakers should continue to pay attention to what happens to first-time homebuyers as real estate investment continues.

“A potential owner-occupant has a very difficult time competing with an investor that pays in all cash, who waives the inspection or an appraisal. So going forward, especially as some of the distressed inventory dwindles, as investors start just buying homes on the MLS like you or me, we need to make sure that owner occupants have a fair shot,” she said.

The new speculation

Following in the footsteps of global investment firm Blackstone’s Invitation Homes and others, American Homes 4 Rent had purchased 34,599 single-family properties in 22 statesby the end of 2014, according to its web site. It has since begun offering rental bonds backed by single-family houses, selling off $552.8 million in debt to investors via bonds in February and March, according to what the company told investors. The rental bond deal is among the first of its kind, egged on by a $479.1 million deal by Blackstone’s Invitation Homes in October 2013. The Blackstone deal paved the way for similar deals, which sell debt and the promise of future payments, by other national rental companies, including Colony Capital and American Homes 4 Rent.

Rental backed bonds aren’t new — they’ve been used extensively in multifamily housing. But the backing of bonds through bundles of single-family rental homes is a new financial tool, one not yet regulated. Rep. Mark Takano, D-Calif., has pressed for Congressional hearings on single-family rental bonds, and has asked the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for regulation and oversight of the bonds. He estimates there are more than 200,000 investor-owned properties across the country, worth in excess of $20 billion. The Center for American Progress has estimated the market for single-family rental bonds could grow to $70 billion by 2016.

Analysts everywhere have scratched their heads about what the entry of these companies into real estate really means. Think tanks like the Center for American Progress and the Right to the City Alliance, as well as researchers such as Desiree Fields, an urbanist and environmental psychologist who studies housing’s role in the capital strategies of large investors, and those at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, have probed this new asset class in a series of analyses since 2013.

The reports partly credited equity-groups-turned-landlords with solving the shortage of high-quality, affordable rentals in some communities, and with helping to stabilize the housing market. But the reports also raised questions about what sort of landlords they will be — whether they will maintain the properties they own, keep management local or scrimp on tenant services, or be quicker to evict struggling tenants than their local counterparts — questions that remain unanswered.

It also isn’t clear, researchers note, how long these firms intend to hold the properties. Or what would happen if any one national landlord stepped out of the market and put tens of thousands of homes, or even a couple dozen in a single neighborhood, up for sale.

“There is a sense that this is an asset class that is not going away anytime soon and I think that it’s leading companies to seek out new markets where there isn’t already a high concentration of investors,” said the Center for American Progress’s Edelman.

Portland fits the profile. There’s potential for appreciation here. And there are a lot of middle-income renters willing to pay higher rents.

In Multnomah County, American Homes 4 Rent has targeted new construction foreclosures on Mt. Scott, in St. Johns, in New Columbia, as well as in Fairview and Troutdale.

Fields notes that social service groups once viewed the crisis as an opportunity, a chance to seize housing at a discount and put it into a land trust. But as they compete with cash for housing, it hasn’t happened. Not as envisioned.

“It seems like there were a lot of missed opportunities in the aftermath of the crisis when we could have thought about pulling housing a little bit away from the speculative model that it’s become,” she said.

Now, observers say communities are left to retool policies to protect renters, and to keep housing ownership accessible. As the city of Portland looks toward solutions, we’ll examine policy possibilities, and reaction, in our next installment of this series.

Additional reporting: Jason Alcorn

Photography: Leah Nash

Editor: Martin Forbes

Executive Editor: Robert McClure