California owners want to build one of the biggest operations in the country, but concerns about energy usage, noise and sustainability stand in the way

By Zachariah Bryan / InvestigateWest

Usk, Wa. — In the bowels of the old Ponderay Newsprint mill, the piercing sound of loud, whirring fans echo off the walls, as thousands of blinking computers stacked on top of one another frantically make trillions of calculations in search of Bitcoin.

The rest of the massive building, full of mechanical contraptions that used to turn wood chips into newspaper, stands silent.

The company that once ran this place went bankrupt a couple of years ago. Now the property has been taken over by California investment firm Allrise Capital, with plans to transform parts of the mill into one of the largest cryptocurrency mines in the state and perhaps, eventually, the nation.

The operation represents an ambitious bet, coming amid the plunge in value of bitcoin from heights of over $60,000 in May to around $20,000 today and the tanking of many crypto mining operations in the Northwest.

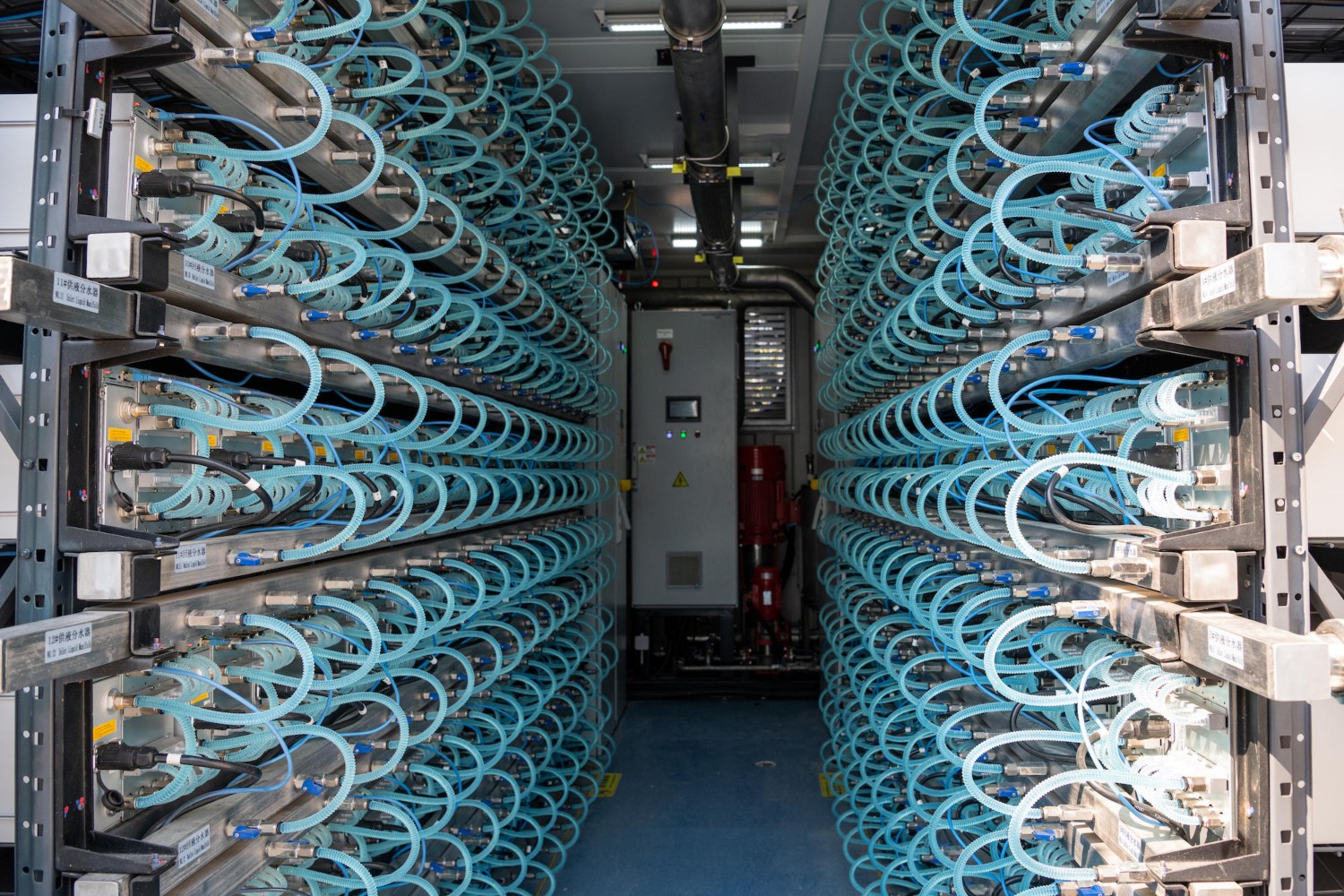

No longer are mill workers parking in the gravel lot outside. Their vehicles have been replaced by state-of-the-art Chinese Bitmain “Antboxes” — decked out shipping containers stuffed with networked computers called “miners” and cooling units. In a process called “proof of work,” computers like these play a giant guessing game to figure out the answers to complex math problems. Solved equations are added as “blocks” to a “blockchain” — a ledger of transactions shared and built and verified by all the computers on the network. Each new block creates a new digital currency such as Bitcoin, which is rewarded to the problem solver.

Crypto enthusiasts contend this process is what makes digital currencies like Bitcoin secure, since no one has the authority to make changes by themselves. But the system also encourages a massive energy drain: More computers “mining” at once means better odds of winning. And these days, companies like Allrise are using a lot of computers.

Announced in February, the partnership with Bitmain calls for 500 megawatts worth of equipment and over 150,000 miners, including new water-cooled units. Ruslan Zinurov, CEO of Allrise, told the crypto-website Cointelegraph that the partnership would “catapult our growth plan of building one of North America’s largest sustainable digital asset mining platforms.”

Usk, an unincorporated town with a population of about 1,000 an hour’s drive north from Spokane, sits along the Pend Oreille River. It’s home to a bar and grill, a general store, and a lumber yard. Until a couple of years ago, the Ponderay Newsprint mill was the largest employer in the county, with about 150 workers.

Residents who moved here expected quiet solitude, to get away from the hustle and bustle of civilization. But the tranquility has been disrupted by the din of crypto mining, said Ben Richards, a U.S. Army veteran who lives across the river.

Now Richards and others are trying to figure out how the new industry is going to transform their little community, as it has transformed others across the nation. And state officials are eyeing the project, wondering if it will disrupt Gov. Jay Inslee’s clean energy goals.

Elsewhere, media reports talk of crypto mining projects humming like jet engines, turning lakes into hot tubs, gobbling up all the electricity and propping up once-defunct coal plants. In a report published last month, the White House recommended that the industry be more closely monitored and regulated, as estimates show it consuming between 120 and 240 billion kilowatt-hours worldwide last year — more than the total annual electricity usage of either Argentina or Australia.

The environmental impacts in Usk are still unclear, as it’s just getting started. But questions remain about how much electricity the project will use, whether it will all come from renewable sources, how loud it’ll get when everything is up and running, and where the computers will go once they become obsolete.

Bubble bursts

Despite the concerns, there is little regulation of crypto mining at the state or federal levels, leaving local utilities to come up with a hodge-podge of solutions.

In the 2010s, digital prospectors journeyed from far and wide to the Columbia Basin in Central Washington, where they could have direct access to hydroelectricity from the region’s dams. A Politico Magazine article detailed tales of old shops and fruit warehouses being turned into mining facilities, of Chinese businessmen arriving in private planes, of outsiders bringing suitcases of cash, and of rogue miners secretly sapping electricity and causing infrastructure damage, as well as at least one fire.

Community members had “substantial reservations,” Steve Wright, former head of the Chelan County Public Utilities District, testified in Congress earlier this year during a subcommittee hearing on the energy impacts of blockchain. People worried about how easy it was for crypto miners to leave based on the whims of the market, thanks to how portable their computer systems were. They also were critical about how few jobs the industry created and wondered if it was the best use of the region’s hydropower.

“Whether cryptocurrency’s value to the society is sufficient for a community to want mining operations based in their area was debated in Chelan County and at best left many of our customer-owners perplexed,” Wright said in his testimony in January.

The utilities in Chelan, Douglas and Grant counties each came up with their own ways to raise prices for crypto miners, due to their large energy loads and the high investment risk they presented.

Some crypto miners left. Others folded or went bankrupt.

“The thrill is gone” is how a recent Seattle Times headline put it.

Those who stayed are more like any other customer, said Louis Szablya, a senior manager at Grant County Public Utilities District. Some are local, with no intention of leaving anytime soon. And while crypto miners’ requests for electricity have been increasing again in the past year or so, the demands have been modest by comparison to those in the 2010s.

“It’s no longer the tail wagging the dog,” Szablya said. “It’s actually just regular customers and regular industries that have been making requests. And then crypto mining is also there.”

Where Washington once was seen as a place where crypto could boom, last November it comprised just 4% of the crypto mining done in the nation, as miners flock to other states that greet them with more open arms, according to the University of Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index.

Since China banned crypto mining, leading companies like Bitmain to send their computers overseas, the United States accounts for about one-third of all operations. The White House report estimated that crypto mining takes up about 1% of the electricity generated in the country, and produces between 25 and 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — similar to the amount of emissions from diesel fuel used by the nation’s trains.

The report also notes that Bitcoin produces over 30,000 tons of electronic waste a year. That’s as much as all the electronic waste generated by the Netherlands. Much of that doesn’t get recycled.

The report recommends the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy help make new standards “for the responsible design, development, and use of environmentally responsible crypto-asset technologies,” with an aim to draw less energy, consume less water and make less noise.

It could be awhile before anything concrete happens, though, as the nation tries to figure out the consequences of the industry.

The real killer

Merkle Standard, a subsidiary of Allrise that manages the crypto operation in Usk, has permission to use up to 100 megawatts of energy per year, exceeding the rest of the Pend Oreille County PUD’s customers combined. It’s also more than than the output of the local utility’s Box Canyon Dam, which used to power the newsprint mill.

That might only be the beginning. Merkle Standard had a study conducted to look at how much it’d have to pay to increase that intake even more, up to 600 megawatts, which would make it one of the largest crypto mining operations in the country. That may be an unlikely outcome though, as the Bonneville Power Administration estimates it would cost more than $100 million to build out infrastructure.

Even getting to 145 megawatts could be expensive. BPA estimates that would cost Merkle Standard over $40 million total.

Either scenario would likely take a few years.

“The real killer is not the amount of money that needs to be put down. It’s the time, the three years,” said Monty Stahl, COO of Merkle Standard.

More recently, the company requested a study to see what it would take to add another 70 megawatts to turn the newsprint mill back on. It’s a promise they made back when Merkle Standard’s parent company, Allrise Capital, bought the facility in 2020 for $18.1 million.

Stahl said he’s committed to bringing jobs back to town and to building a “sustainable” operation. He estimates crypto mining could bring in 40 jobs, and the newsprint mill another 150. Whether Allrise is serious about bringing the newsprint mill back online has been the source of much local speculation.

According to Stahl, the company is buying renewable energy credits, and while it isn’t getting power directly from nearby hydropower projects, he believes the proximity of the facility naturally takes advantage of those resources. (Tracking where electricity comes from is not an exact science.) Plus, he said, the company can work with the PUD to curtail its energy use during times of peak demand.

Not only can crypto mining be carbon neutral, Stahl argued, it can be “carbon negative,” by repurposing heat generated by the servers. For example, last winter, that heat was used in place of propane to warm up the newsprint mill, which one day may be reactivated.

Skeptical of sustainability

Anything that takes so much electricity can represent “an opportunity that is lost,” said Glenn Blackmon, senior energy policy adviser with the state.

That power could be used to help build out electric vehicle charging infrastructure, or to convert buildings from natural gas to high-efficiency electricity, he said.

“We need a lot of clean electricity … to do the energy transformation of our economy, that is necessary for us to meet our climate goals,” Blackmon said. “And adding a novel load like blockchain processing, at best, is an additional requirement for clean electricity.”

There is also a scenario, Blackmon said, where Merkle Standard could wind up in a situation where it negotiates to get power from somewhere else, possibly introducing fossil fuels to the mix, he said. He said the state’s Energy Office will be pitching the Legislature to close a loophole in the Clean Energy Transformation Act and prevent that from happening.

Otherwise, the state isn’t getting in the way of the project. Just keeping an eye on it. It isn’t really in the state’s purview to decide what is or isn’t a good use of electricity, Blackmon said.

“There’s lots of different things people might do with electricity that they haven’t done historically,” he said.

The potential environmental threat of cryptocurrency has garnered a few local opponents in Pend Oreille County, who have caused a couple of hiccups.

Richards, the Army veteran who runs a website called Protect Pend Oreille, and retired biologist Ed Styskel protested the county’s determination of non-significance for the project. Both argued that Merkle Standard was not forthright in how loud the full operation could be and how that noise might affect local wildlife, like the American white pelican that hangs out in the area part of the year.

In May, the county hearing examiner shot down the appeal and approved the conditional use permit, with the requirement that the crypto operation follows state noise rules.

Stahl calls Richards a “fiction fantasy writer.” Stahl contends the old wood chip processor was louder than the crypto equipment. But, Richards notes, the processor didn’t run 24/7.

The crypto operation has also come under fire from Responsible Growth NE Washington, a local environmental group that got its start five years ago protesting — and effectively chasing away — a proposed smelter in nearby Newport.

“When you want that much power, somewhere along that line … you’re going to find coal,” said Phyllis Kardos, a retired teacher and a leader of Responsible Growth.

Kardos says she isn’t opposed to reviving the mill and bringing back those jobs. But she worries about the impacts of an industry that takes up so much electricity and, in her view, gives so little back.

“Someone has to speak for the environment,” she said. “People want to come here, not because of a smelter, or not because of a cryptocurrency. They want to come here because of the rural lifestyle, the environment that we have now.”

One question that remains is how long Merkle Standard will last in the current market conditions.

Maybe the market will swing up again, as it has done before, and Merkle will reap the profits.

Or perhaps the company will do as others have, and take its miners to cheaper pastures. Merkle already shipped some computers to a server farm in South Carolina, where Stahl said the process was much smoother.

For now, Stahl says they have no plans of leaving Usk. As long as it makes business sense to stay.

“Maybe I’m just a sucker for Northeast (Washington) because I grew up in Colville,” he said. “But whenever I can, I’m gonna try to build it here. If it becomes economically unfeasible, we’ll go somewhere else.”

FEATURED IMAGE: Ant Boxes (with SR-20 in the background) outside the Merkle Standard cryptocurrency mining facility in Usk, Wash., on Friday, Sept. 9, 2022. (Erick Doxey/InvestigateWest)

CORRECTION: The article has been updated to correct the amount of carbon dioxide produced by crypto mining and the wood product used in making newsprint. It also clarified that the mill’s wood chip processor had not operated 24/7.

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Visit invw.org/newsletters to sign up for weekly updates. This story was made possible with support from the Sustainable Path Foundation.