The law was supposed to make Oregon compliant with the Feds. It failed.

Bob Terry flew home from Washington, D.C., in early September 2001, confident that a long-negotiated immigration reform deal was imminent. Then a member of the Oregon Association of Nurseries, Terry had a stake is making sure his members’ employees — many of whom he guessed had entered the country illegally — had more than job security. They needed a path to citizenship.

“I was sitting down with Ted Kennedy, Dianne Feinstein — just a whole host, including Cesar Chavez’s son — to try and get the immigration bill worked through,” said Terry, a Republican who later became a Washington County commissioner. “And it was ready to go. It was going to go that Friday. And then 9/11 happened.”

Stories saturated the media of how 19 men had come into the United States from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon and Egypt and boarded planes using illegally obtained driver’s licenses. It was just the fuel Jim Ludwick needed.

Ludwick had moved to Oregon from California three decades earlier and bought 40 acres in the hills west of McMinnville, where he built a house with windows to look out on the Yamhill Valley.

In 2000, after retiring from a career as a pharmaceutical salesman, Ludwick launched Oregonians for Immigration Reform to lobby for laws that would make Oregon a less-welcoming place for undocumented immigrants and immigrants who didn’t assimilate. At the time, Oregon didn’t require residents to show proof of legal immigration status when applying for a driver’s license. Ludwick made changing that the priority of his new group.

Lawmakers, however, didn’t want to be seen talking to him at first.

Bob Terry, former head of the state nursery growers association, says agricultural workers need to be able to legally drive, regardless of their immigration status. Photo by Mateusz Perkowski.

“A senator would walk by, and I’d introduce myself and tell him why I was there: ‘I’m opposed to driver’s licenses for illegal aliens,’” Ludwick said. “And he’d say, ‘I agree with you, but it’s too hot of an issue.’ And that’s the way it was for the first couple of years.”

What finally changed the conversation wasn’t a shift in attitude about Latino residents, but a post-9/11 focus on border security.

The federal Real ID Act of 2005 required states to restrict driver’s licenses to those who could prove they were here legally. Many states, including California, already required proof of legal status. Most others moved toward compliance, while some — like Utah — opted for a two-tiered system, granting formal licenses to those who could produce legal documentation, and a limited drivers’ card (which can’t be used as federal identification or to board a plane) to those who could not.

‘Are we really doing the right thing?’

Oregon grappled with the issue until November 2007, when Gov. Ted Kulongoski issued an executive order calling on the state to require that residents prove their legal immigration status to obtain or renew a license.

At a Senate hearing the following February, during the short session, Sen. Alan Bates, D-Medford, complained the bill had been pushed through with little debate and no chance to offer amendments. A short session — normally reserved for budget adjustments and minor legislative matters, wasn’t the time to address serious concerns. And this bill, he said, raised serious “moral and ethical issues.”

“I haven’t heard anything that makes me feel safe tonight with what we’re doing here tonight. The people we are affecting are our friends and neighbors,” said Bates, who died last year. “Think long and carefully. Do we really need to do this tonight? And are we really doing the right thing?”

While a few Democrats, including then-Senate Majority Leader Kate Brown, opposed the bill, most joined with Republicans and overwhelmingly agreed it was the right thing.

Sen. Laurie Monnes Anderson, a Democrat representing an estimated 9,700 noncitizen Latino residents of Gresham, voted for it. “The lax standard of driver’s licensing in Oregon has made our state a target for criminal organizations and more vulnerable to identity fraud,” she told the Capitol Press.

Senate President Peter Courtney, a Salem Democrat whose district included Woodburn and its estimate 6,300 noncitizen Latino residents, did too. Jeff Merkley, then House Speaker who was running for federal office, cast his vote in favor.

Immigrant rights groups turned out more than 15,000 people to rallies at the state Capitol protesting the bill, to no avail. The new law resulted in the most profound change for Latino families in decades. Few lawmakers seemed to realize the enormity of a move to prevent up to 83,000 undocumented workers from getting or renewing their licenses.

“They look at the polling, they read the tea leaves and connect it to their own political careers. It’s all about their seat, self-preservation, keeping the majority in the Legislature” said Andrea Williams, executive director of Causa, a Salem-based nonprofit working for immigration rights. “A lot of decisions came down to Gov. Kulongoski. And he made the political decision to restrict drivers’ licenses.”

Activists like Williams knew Republicans would be less likely to support their cause. But the eagerness of Democrats to join them was a stinging surprise. “Democrats are not being bold on our issues, but they’ll at least talk to us,” she said. “And then on the driver’s license issue, they completely betrayed us.”

Kulongoski, contacted at his home, declined to comment. Merkley did not reply to requests for comment.

Monnes Anderson and Courtney said the federal legislation allowed for a driver’s cards, like those used in Utah at the time. Both assumed the Legislature would quickly adopt that system in Oregon.

Five years later, they tried.

Reversing course

Restrictions of driving privileges for undocumented immigrants, which swept the nation after the Real ID Act of 2005, have begun to soften. Today, 12 states and the District of Columbia extend privileges to undocumented residents. They include Washington, California and Nevada.

Oregon lawmakers also tried to reverse course. In May 2013, Gov. John Kitzhaber signed into law a bipartisan bill allowing for a driver’s card distinct from the formal license that would allow people to drive legally without proving citizenship.

The logic was that it would ensure drivers knew how to drive and allow them to get insurance, which most agencies refused to sell without a valid license. But the card couldn’t be used for federal purposes such as to board a plane.

Ludwick saw Kitzhaber’s actions differently: “He wants to allow people to legally drive to jobs they can’t legally have, hired by companies that can’t legally hire them,” Ludwick said.

Within hours, Oregonians for Immigration Reform vowed to take the matter to voters. Privately, Ludwick didn’t think they had a chance of collecting enough signatures to get the referendum on the fall ballot. “How do you collect 70,000 to 80,000 signatures in three months?” he said. “If there was a tote board in the rotunda giving odds, we’d be 1,000-to-1 underdogs.”

They called on Suzanne Gallagher, then chairwoman of the Republican Party. She promised to get signature sheets to every Republican in the state. Meanwhile, Ludwick and his supporters fanned out to county and state fairs. Ludwick said people were eager to sign.

“They would grab the sheets out of your hand,” he said. “We got signatures from places I didn’t even know existed. We got ‘em from 134 different communities.”

The group had more than grass-roots support. Conservative Nevada businessman Loren Parks shelled out $93,172 over five weeks to pay signature gatherers. In the end, the campaign turned in 58,291 valid signatures, squeaking by with a buffer of 149.

In the November 2014 election, voters crushed Measure 88, the Legislature’s driving card law, by a 2-1 margin. Every county except Multnomah voted against retaining the law.

“That stunned us,” Courtney said. “We didn’t think that could happen.”

Courtney’s support of Measure 88 became an issue in his 2014 re-election campaign, as he battled claims that he supported giving driving privileges to drunken drivers and criminals living here illegally. “It was probably the ugliest racial issue I’ve seen since I lived in the South,” said Courtney, who was re-elected that year with 54 percent of the vote.

Mike Nearman, a software engineer from Independence, said he wore out two pairs of shoes volunteering 11-hour shifts at the Oregon State Fair to oppose Measure 88.

He said his efforts were targeting people who didn’t come into the United States legally.

“I wish everyone could live under the freedoms I enjoy. I don’t begrudge anyone, but we just need to do it legally,” he said. “What we have right now is not the best and the brightest, but the boldest and the baddest, whoever’s willing to jump the fence.”

Nearman went on to join the board of Oregonians for Immigration Reform and win election to the state House of Representatives. He’s advocating for a repeal of Oregon’s restriction on local police from enforcing immigration law.

Gilbert Carrasco, a Willamette Law School professor and former civil rights litigator for the federal Department of Justice, said the legislation to require drivers to provide proof of legal status to obtain a license doesn’t make sense.

“The argument was, ‘They shouldn’t be here,’” he recalled. “Well, they’re here. They’re not going anywhere. Now we’re in a situation where people are unlicensed, they haven’t been tested” by the Department of Motor Vehicles.

And many are uninsured.

“It hurts the people who voted for that law. That’s the irony,” he said. “At some point, if the Legislature, if the people, don’t revisit it, I think the courts will.”

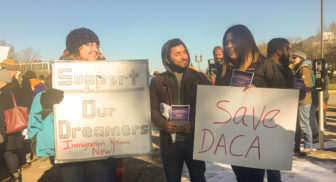

Demonstrators march around the Oregon Capitol Saturday, Jan. 14, 2017, in opposition to President-elect Donald Trump’s positions on immigration. Photo by Paris Achen.

You end up in trouble

Advocacy groups haven’t given up on the concept of a driver’s card, and they continue to pin down lawmakers on their positions.

Sen. Monnes Anderson, for one, would support it. “Obviously, we’re all better off when everyone who is driving a car that is licensed and insured,” she said.

Sen. Courtney is frustrated by the Legislature’s inability to respond to the voters’ rejection of the driver’s card. “We are really struggling to break through on that,” he said.

Washington County commissioner Terry watched the 2008 legislative vote to restrict licenses and the 2014 referral to vote down driver cards with frustration. A prominent and active Republican, he sees the past 16 years as a wasted opportunity and isn’t optimistic about the future of immigration reform in Oregon.

“As a state, we were foolish and didn’t accomplish anything,” he said. “We’re not really managing that issue. And any time you don’t manage an issue, you end up in trouble.”

Unequal Justice is a joint project of InvestigateWest and the Pamplin Media Group, made possible in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism. Researcher Mark G. Harmon from the Portland State University Criminology & Criminal Justice Department provided statistical review and analysis.