On the surface, it looked like a good deal for Oregon schoolteachers, firefighters, police officers and other public employees. Post-recession, the public employees’ pensions would be invested in a new way of making money: buying up and then renting out the multitude of single-family homes sitting idle in a slumping housing market.

But those decisions by a state investment council — including Ted Wheeler, currently a major candidate for Portland mayor — directed at least $600 million worth of those public pensioners’ investments into two funds operated by the global investment firm The Blackstone Group.

The result is that the Oregon Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) and others tied to Blackstone are now poised to capture the upside of the housing recovery. But they will do it on the backs of renters, and while competing with would-be homeowners for the lowest-price housing on the national market.

Blackstone’s Invitation Homes now leads the market in a strategy to use single family homes as a vehicle to return profits to investors, aiming to raise rents, and shifting the burden of home ownership onto renters. It marks a departure from the past, when real estate investments tended to concentrate on apartments, not single-family homes. In a recent survey in California, where Blackstone owns an estimated 5,000 homes, renters’ rights group Tenants Together found those leasing from the Blackstone and two other Wall Street landlords paid more in rent than typical renters pay for all housing costs. They also absorbed other costs: Nearly half reported making home repairs themselves, 80 percent said they were paying for yard maintenance, and almost all had higher utility costs than average tenants.

Oregon’s investments in Blackstone were authorized by the Oregon Investment Council, the six-member council that approves PERS investments for the Oregon State Treasury. The council includes Wheeler, who has made affordable housing a major focus in his bid to be Portland’s next mayor, saying on his website that he will “fight to create more affordable housing options so our nurses, teachers, firefighters… can continue to live and prosper in Portland.”

The situation illustrates the disconnect between concern about rising housing costs and this reality: Wall Street’s efforts to profit off of rising rents and the rebounding price of houses have been backed by the retirement funds of people hard hit by both.

Oregon is not alone. Blackstone culls a third of its total investments from public pension funds worldwide. And across the nation, public pension funds invested an average of 7.5 percent of assets invested in real estate as of June. California legislators proposed strategies to avoid real estate deals that disrupt housing affordability in 2010, but the effort failed. But even while the Portland Police Bureau will soon pay incentives to officers who live in the city — a balm for rising costs — there’s been no talk about pension investments in real estate deals that drive rents and home prices skyward.

“It’s going to increasingly be a question raised when it comes to these funds,” said Phil Keisling, Director of the Center for Public Service at the Mark O. Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University. That’s particularly true because PERS and other pension funds are obligated to seek annual returns of 7.5 percent or more, a higher burden than in the past, he said.

Returns like that don’t come from safe, long-term bonds anymore. They come from a diverse investment portfolio that may include investments that conflict with policy goals.

PERS investments

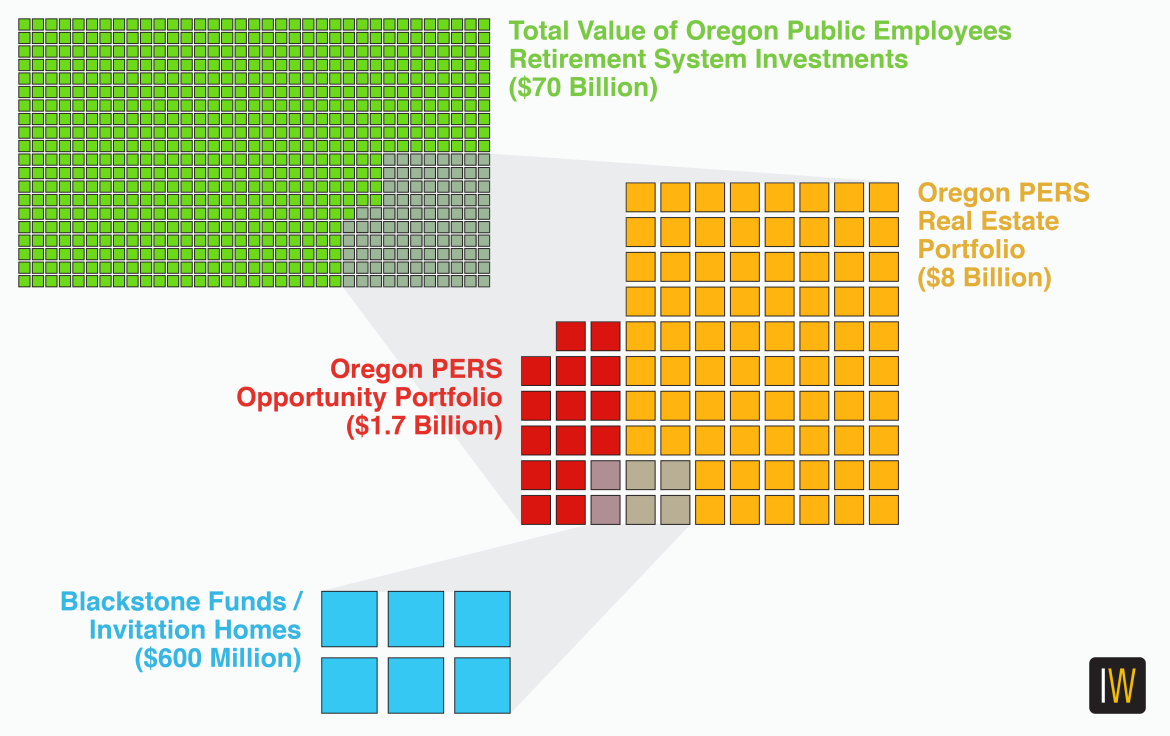

Oregon has invested $70 billion in PERS funds on behalf of public employees. Those investments are advised by staff in the treasurer’s office whose job is to spot the best opportunities for the fund’s growth, then pitch them to the Oregon Investment Council for approval. All are bound by laws that require the fund deliver returns to public pensioners. Currently, $8 billion is invested in real estate through dozens of funds and trusts. Another $1.7 billion is reserved for unique opportunities, and that fund also includes real estate investments.

The Oregon Investment Council committed $600 million from both areas to two Blackstone funds between 2012 and 2014, both of which helped pave the way for Blackstone’s entry into the single-family housing market. The funds provided capital to Invitation Homes, Blackstone’s home-buying subsidiary that now serves as landlord to more than 45,000 single-family homes in 14 areas around the country.

“That is out of the millions of family homes in the U.S.,” said Blackstone spokesman Peter Rose. “It’s very hard to see how that would make a difference one way or another in terms of housing affordability.”

Blackstone’s advance on the housing market was a direct outgrowth of the housing crisis.

Blackstone doesn’t yet own single-family homes in Oregon. But ripple effects spring from Blackstone copycat American Homes 4 Rent, which has competed directly with first-time homebuyers in the Portland area, an InvestigateWest analysis found. The company has strategically targeted Portland families for rent hikes and fees designed to boost returns for Wall Street.

So far, no one has suggested PERS divest of the Blackstone investments. And the Oregon State Treasury does not have the authority to do so alone. The Oregon Legislature would instead have to act. State Treasury spokesman James Sinks said such a move could open a door to lawsuits because federal tax rules require PERS funds to be used for the exclusive benefit of the beneficiaries.

But Keisling and observers of the housing industry suggest there should at least be an effort to disclose such investments, and create awareness about their impacts.

“It is important that we look really closely at the costs and benefits of where we’re putting publicly controlled resources,” said Janet Byrd, who convenes the Oregon Housing Alliance, a coalition of community and government groups that advocates for affordable housing. Byrd said more strategic investments by public pension funds could influence markets to the advantage of Oregonians with low incomes.

Some PERS funds already do that. For example, the Oregon Investment Council has put billions into investments tied to the U.S. mortgage market, some of which were used to purchase distressed loans and restructure them to collect payments. The struggling homeowners who paid would have otherwise faced foreclosure.

Duke University finance professor Campbell Harvey also points out that while companies like Invitation Homes, which increase property values in a distressed market, might disadvantage a first-time homebuyer, they can also buoy the house values for home-owning retirees. That’s why pension funds like the investments, Harvey said — they target undervalued assets and make them stronger.

“This is exactly the kind of investments that pension funds should be making. It’s something I’ve been saying for years: pensions should be at every fire sale,” he said.

In New York, on the other hand, pension funds are taking steps to steer investments into the creation of new affordable housing units, including putting $150 million in a union-led housing trust as part of a $1 billion union effort to build and sustain affordable housing using union labor. Should the Oregon Legislature adopt rules to bring pension investments more closely in line with policy goals, it wouldn’t be the first time. The legislature has previously adopted rules to limit pension investments in response to apartheid, genocide, and sponsorship of terrorism. All involved divesting from companies doing business in the countries at issue.

Sudan and South Africa “are pretty much the poster children of investment ban,” said Hank Kim, executive director and counsel for the National Council on PERS. “The real issue is how do you balance fiduciary concerns with some of these ethical and humanitarian concerns? Also to the extent that pension plans do want to effect change, what is the best course of doing that?”

In answer to InvestigateWest inquiries, Wheeler declined to speak with a reporter or answer questions. Sinks, the Treasury spokesman, said Wheeler didn’t want to run afoul of other fiduciaries in suggesting fund investments, and that, generally, mingling politics and pension funds is a bad idea. Wheeler issued a statement emphasizing that it is the state’s duty to diversify pensioners’ investments to protect their retirement earnings:

“Oregon trust funds are diversified across markets and strategies for the financial benefit of taxpayers, schoolchildren, injured workers and public retirees, and Oregon’s pension fund has been rated as one of the best-managed in the country. One of the fund’s key long-term strategies is expanding real estate supply, which will help long-term returns, meet market demand and stabilize prices,” Wheeler’s statement said.