Pandemic relief funds are bankrolling new – and often unregulated – law enforcement tools such as license-plate readers, drones and AI video software.

By Brandon Block / Crosscut.com / July 26, 2023

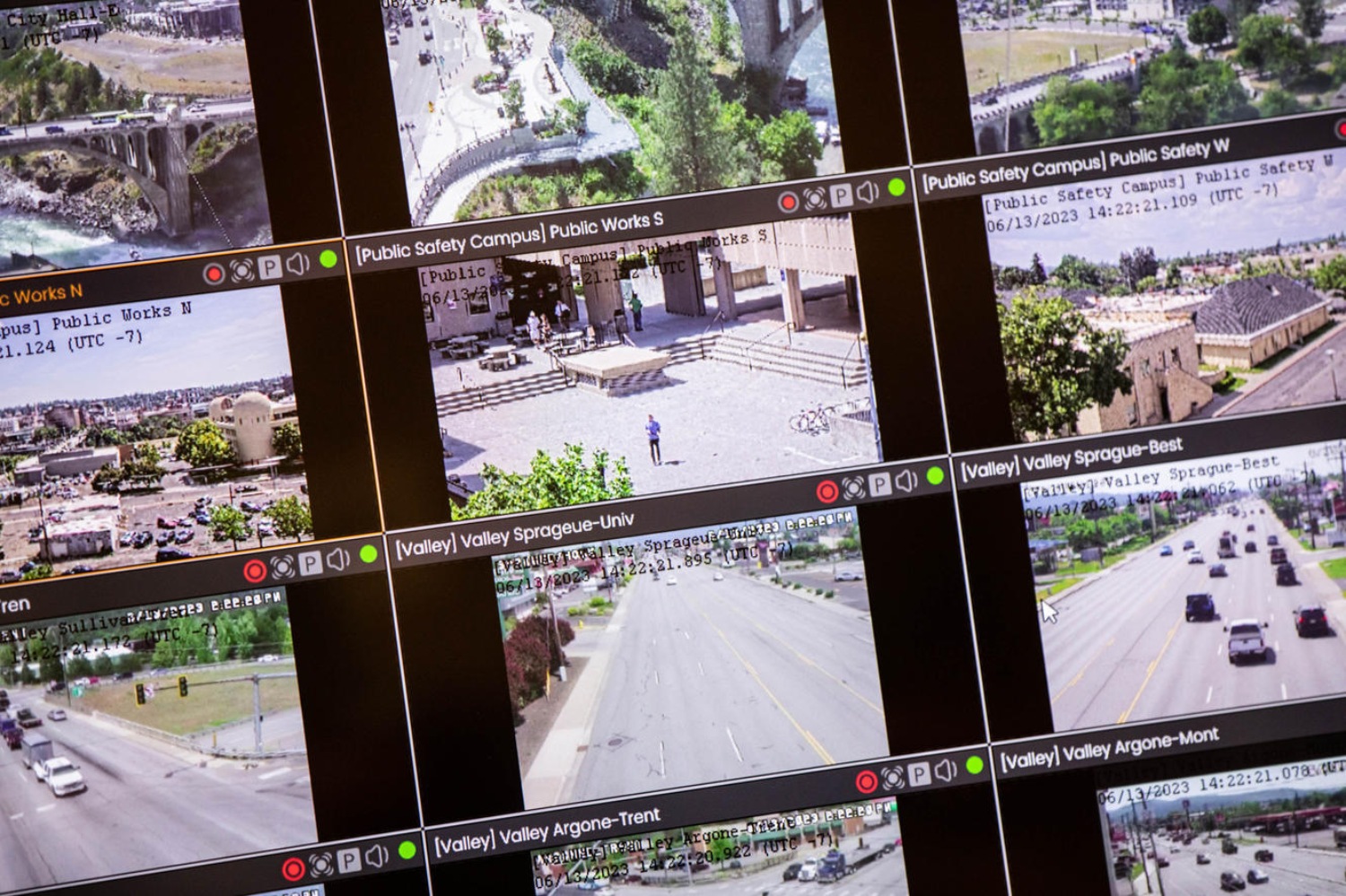

In a corner of the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office, an array of 11 wall-mounted TV screens displayed live maps with icons tracking 911 calls and officers, social media posts and various video camera feeds – ranging from county buildings and busy intersections to a car wash and a construction site.

A red circle radius appeared on one map as a female voice patched through a small speaker.

“I just passed Spokane Community College,” the voice said. “The intersection on Houston and – I can’t see the signs but there’s a drunk driver.”

Lt. Justin Elliott turned up the volume knob on the speaker. He wore a star-shaped badge on his belt, and handcuffs dangled off his hip. “You’re hearing a live 911 call coming in,” he said.

A dispatcher asked the caller what kind of car she saw, and which way it was going.

Elliott turned to a screen running a program called Flock Safety, a searchable database that collects photos from a network of 46 Automated License Plate Reader (ALPR) cameras placed at high-traffic intersections throughout the county. He wanted to see if any cars matching the caller’s description were recently clocked in the area.

ALPRs take still photos of every passing vehicle and scan their plates. Each scan is then logged and cross-checked with a national FBI database, and officers are alerted whenever there’s a “hit.”

The sheriff’s office also has another powerful new surveillance tool: $150,000 “video analytics” software that uses machine learning to scrub through days of footage in minutes and make it searchable using descriptive keywords. Manufacturer Briefcam advertises its pioneering use of facial recognition, though Spokane deputies said they asked for that feature to be disabled.

Next to Elliott, crime analyst Dustin Baunsgard, tall with a beard and glasses, pointed at the screen and noted a unit close to the caller’s location.

“Before dispatch even gets it we could have that information out to that particular officer,” he said.

Spokane County’s advanced tech tools will all feed into this Real Time Crime Center, a multi-city effort to create a surveillance hub that sheriff’s deputies hope will speed response times and convert data leads into solving crimes. The $5 million project, funded primarily through American Rescue Plan dollars, will also drastically expand the sheriff’s department’s ability to peer into the lives of people not suspected of committing crimes.

Across the state, one-time federal relief dollars are bankrolling increasingly sophisticated means of surveilling the public with few legal safeguards. Local governments have acquired mobile camera trailers, license-plate readers, gunshot detection software, drones and body cameras, and have installed security cameras in parks, marinas, jails and courthouses.

The expanded digital dragnet has the potential to feed into advanced AI-powered tools like facial recognition – which research has shown can reproduce the biases of its operators, potentially amplifying existing discriminatory policing practices against communities of color.

Police credit new technology with helping solve crimes amid heightened public safety concerns, but on the local level these technologies often roll out with little oversight, leaving departments to decide for themselves, for example, if they want to use the data to assist with immigration enforcement or share data with states where seeking an abortion is a crime.

“Some people will always support it and say, ‘Well, it’s fine with me because I don’t have anything to hide,’” said Jim Koenig, a defense attorney in King County. “But history shows that law enforcement and governments are very bad at regulating themselves, so the application gets broader and broader and generally moves into various kinds of social repression.”

In a June 13 photo, Lt. Justin Elliott, a member of the investigative division of the Spokane County Sheriff’s office, explains how to use one of the programs that operate cameras used in their temporary ‘Real Time Crime Center.’ The Center will analyze footage from various surveillance camera feeds to aid in police work. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Public safety and personal privacy

Jennifer Lee pointed up at a camera affixed to a streetlight pole at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Pine Street in downtown Seattle. It was a hot July afternoon and the sun gleamed off glass skyscrapers. A block away, hundreds of people gathered in Westlake Park, next to Seattle’s main shopping area, for an outdoor concert.

The camera snapped images of the license plates of every driver passing through. Behind Lee, dome-shaped cameras sprouted from the overhang of Nordstrom. On her walk here, Lee passed a traffic-signal control box sporting a small black disc that recorded her location and her cell phone’s unique address.

“The thing we’re always concerned about is mission creep,” said Lee, the technology policy program director for the ACLU of Washington. “Even if they’re not originally intended for the purpose of surveilling individuals or being used to deport immigrants or harm individuals, oftentimes it ends up being that.”

For those uneasy about empowering law enforcement, American history offers countless cautionary tales: the FBI infiltrating civil rights groups in the 1960s or, more recently, the NYPD tailing worshippers at mosques in the years after 9/11.

Policies to prevent the abuse of surveillance have historically lagged behind the creation of new tools. And as the pace of innovation speeds exponentially, new AI-powered tools raise the specter of amplifying existing biased policing practices.

The American Rescue Plan Act authorized $350 billion in direct, flexible federal money to city, county, tribal and state governments across the country. Law enforcement agencies have proven well-positioned to vie for that money. Crosscut reported last year on the millions directed to tasers, squad cars and officer bonuses across Washington.

As federal stimulus dollars enable local law enforcement to invest in broader monitoring, attorney Koenig said he sees echoes of the post-9/11 militarization of policing as the Department of Defense surplused military-grade weapons out to small-town departments. (Yakima County also recently bought a $350,000 armored “Bearcat” vehicle with rescue plan funds.)

“It wasn’t so long ago that the kinds of armaments being given to the states and localities were like heavy machinery, like SWAT machines and artillery – basically old-fashioned weapons of war for use in the populace,” Koenig said. “The trend is that you [now] have new technologies being employed in service of first the military and then filtering down to law enforcement at the various levels.”

Flock Safety and other tech manufacturers describe their programs as “force multipliers” that help overstretched local departments efficiently monitor their communities. Police departments across the country have credited such technology with locating missing persons, accelerating response times, recovering stolen property and cracking cold cases.

Logging license plates

License-plate reader cameras have been around for over a decade, but have become more ubiquitous in the past few years, in part thanks to the windfall local governments received during the pandemic.

They also serve, detractors argue, as an instructive case study in the potential dangers of unregulated mass data collection.

In Yakima County alone, commissioners spent more than $600,000 of American Rescue Plan money to equip every municipal police department with readers, offering newfound capabilities to towns of fewer than 5,000 residents like Moxee and Wapato.

Users of Flock Safety’s software see a drop-down menu that allows them to check or uncheck 15 options within the FBI database. Categories include missing persons, Amber Alerts, and stolen vehicles – but also identity-theft victims and suspects, people on supervised release, and “immigration violators,” a broad category that can include undocumented people with “administrative warrants for removal” who have not been accused of crimes.

In the absence of specific state regulations on license-plate reader usage, police departments can make (or not make) their own policies governing whom they track, how long to retain data, which employees can access the database and how widely to share data.

The Yakima Police Department, which has used car-mounted plate readers since 2015, lets individual officers decide what types of hits to track. Administrative Lt. Tory Adams said every officer in the department has the ability to add plates to the hotlist and can access the database of logged plates. Adams said the hotlist is used to track a wide variety of people, including shoplifting suspects.

In a recent one-month period, Yakima’s cameras logged more than 360,000 unique plates in a city of just under 100,000 people. Adams said it’s fair to say that most people driving around have likely been logged by the cameras. While in the past the department had no data retention policy, it now reports purging data after 30 days on its transparency portal.

A recent report from the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights warned that the vast quantity of data gathered and shared by license-plate reader cameras could aid attempts to deport migrants or prosecute out-of-state residents seeking abortions in Washington – two things state legislators have passed laws to discourage. The report cited Yakima, as well as police departments in Vancouver and Okanogan County, for feeding plate scans into commercial databases accessible to federal immigration enforcement agents and sharing plate data with police departments in states where abortion is a crime.

“When indiscriminately-gathered data is broadly shared, and particularly when it is integrated with algorithms and data from other forms of surveillance, it becomes possible to use ALPR data to identify individual drivers and track their movements in real time,” the report reads. “This could permit the use of ALPR data to undermine Washington’s commitment to immigrant and reproductive rights.”

State legislators have passed numerous bills affirming access to reproductive healthcare since the overturning of Roe v. Wade. And under the Keep Washington Working Act, police officers are prohibited from stopping people solely for immigration enforcement. Lawmakers in California have banned the practice of sharing location data with out-of-state law enforcement agencies.

There are other concerns about how plate readers could be abused. In Texas, several police departments use the cameras to track people who owe court fines, pulling over drivers and making them pay on the spot or face arrest. A report from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital civil rights nonprofit, describes how Vigilant Solutions provides the equipment at no cost to the police but adds a 25% surcharge to the driver – functionally enlisting officers as debt collectors.

In Spokane, crime analyst Baunsgard is quick to note they do not set alerts for the “immigration violator” category, and said they have asked Flock to have that option removed, but he could not confirm that had happened yet.

While Spokane has yet to adopt any official policies, Baunsgard said just a few other Spokane analysts and dispatchers are authorized to add plates to the hotlist, and they currently use the hotlist sparingly – between six and 10 entries per week – only adding plates connected to violent felony crimes where they have an “actionable” lead. By starting slowly, Baunsgard said, he hopes to head off concerns that the hotlist might be utilized to go after frivolous nuisances or crimes of poverty.

“That is absolutely my No. 1 concern, is I want to make sure that what is on that list is there for a valid and legitimate reason,” he said. “We don’t have time to indiscriminately track random vehicles,” he added, “but that’s beside the point. The capability is there, so we want to use it responsibly.”

Investing in surveillance

In his proposed budget late last year, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell pitched spending $1 million on gunshot detection system Shotspotter (which recently rebranded as SoundThinking). The City Council ultimately rejected the idea, with members Teresa Mosqueda and Kshama Sawant citing research suggesting Shotspotter failed to produce evidence of gun crimes.

Seattle’s 2018 transparency law has produced a relative abundance of information about how city agencies collect and utilize surveillance data. Residents can consult the city’s website for a master list of 26 technologies currently in use and policies restricting their application, or peruse a 350-plus page report on SPD’s use of license-plate readers. A civilian oversight board reviews those reports.

But across the state, local officials have used stimulus cash to purchase a wide variety of new surveillance tools. Residents of cities without robust transparency laws or civilian oversight like Seattle’s may not hear when police adopt such technology.

Yakima police already have acoustic gunshot detection devices made by Flock Safety, although they’re currently experiencing technical issues. According to Adams, the company threw in a free trial when city officials bought the license-plate cameras. Gunshot detection is also under consideration by the City of Spokane.

Other tech upgrades include mobile camera trailers in Spokane Valley, video cameras for parks and marinas in Oak Harbor and drones for Burlington and Centralia. At least 17 jurisdictions in Washington reported purchasing body-worn cameras for police with federal rescue plan funds, according to U.S. Treasury data.

Loopholes in federal reporting rules, however, may obscure the scale of new police tech purchases. Yakima County’s order of just under 200 license-plate readers, for example, is not apparent from federal data, which allows governments to lump expenses into a catch-all category called “revenue replacement.”

“It just makes you wonder,” Lee said, “if we invested the millions of dollars going into surveillance technologies that have proven to be inaccurate and harmful and ineffective, like Shotspotter, instead diverting that kind of money, those millions, into education programs or healthcare programs, what that could actually do to benefit communities?”

A facial recognition frontier

Waiting for a traffic light on Seattle’s busy Fifth Avenue, Lee gazed up at the IBM building, an office that itself resembles the lattice-hatching of a desktop computer tower. She brought up the recent debate around generative AI. Even the people developing robots, as a recent New York Times story details, are warning of its destructive potential, yet it seems hard to imagine that a serious proposal to stop, or even limit, its development would gain traction.

All of these ever-expanding image-based policing tools as well as private surveillance systems — body cams, license-plate readers, drones, Ring doorbell cameras — could potentially feed into facial recognition programs to identify and track individuals in unprecedented detail.

“There’s an assumption that technological advancements are inherently good and they’re inevitable,” Lee said. “[But] does it actually have to happen? … If the risks are so large and the harm to communities is so damaging, why are we pursuing pushing these technologies forward with these mitigation strategies?”

Lee qualified that the ACLU is not categorically opposed to all surveillance – they see the value in using drones to survey natural disasters, for example – and their emphasis is generally on ensuring tech is used in a transparent and narrowly defined way.

But AI-powered facial recognition is one technology on which the ACLU has called for an outright ban – or at least a moratorium until regulators can grasp the ways it could backfire and design restrictions around its use. They also see no acceptable use of predictive policing, software that mines social media to speculate about who might commit future crimes.

In 2021, voters in Bellingham passed a ban on both these technologies. That same year, King County banned facial recognition from being used by county departments – though the law as written does not apply to city police departments within the county.

A 2020 state law requires that police departments notify local officials, produce an “accountability report” and hold public meetings before obtaining the technology – but these requirements don’t apply if the department already had the technology when the law went into effect.

Municipal police departments in Auburn, Bellevue, Kirkland and Redmond have been experimenting with facial recognition since at least 2016, according to emails published by the ACLU, but it’s unclear if those cities have continued to use facial recognition since then. The 2020 state law does require disclosure if a department wants to renew its contract.

Another part of the law states police need a warrant to conduct “ongoing surveillance/persistent tracking” except in undefined “exigent circumstances.” It directs judges to report any such warrants to the Administrative Office of the Courts, which told Crosscut it has received no reports of such warrants since the law’s passage. However, the law requires reporting of warrants only after they expire or if they are rejected, meaning that active warrants are not disclosed.

Crosscut reached out to courts in King, Pierce and Spokane counties seeking copies of any warrants issued for “ongoing surveillance/persistent tracking” since the law was passed. Spokane and King counties both said they were unable to track warrants by this specific type, and a Pierce County clerk said he looked through a batch of warrants since the law was passed, but did not find any relating to the use of facial recognition for ongoing surveillance.

Gary Ernsdorff, a supervising attorney in the King County Prosecutor’s office who works closely with police investigations, said that he was not aware of any such warrants and was confident that he would know about them if they existed. But he also cautioned that such warrants would likely be sealed to avoid tipping off the person being watched.

The ACLU was critical of the state law when it passed in 2020. Lee said it allows for broad use of facial recognition to surveil crowds in public places, such as protests, and that there’s no penalty for flouting the transparency rules.

In her view, technologies like facial recognition exacerbate existing biased practices within police departments. Studies of facial recognition have shown it to be less accurate at identifying women and darker-skinned people.

“Throughout history surveillance has targeted marginalized communities,” Lee said. “Now we are talking about technology [that] we can’t even understand how it’s being used.”

‘Community caretaking’

Where critics like Lee are attuned to its potential for abuse, proponents of high-tech surveillance tools are apt to see machine efficiency as a means of transcending human error.

Under the glow of the crime center’s multiple video monitors, Spokane County Sheriff’s Lt. Elliott described a vision for how this new technology could avoid the past missteps of controversial police strategies like stop-and-frisk or broken-windows-style crackdowns on minor infractions to discourage more serious crime.

“The old way of police work was, we’ve got a high-crime area right here, let’s flood that with officers and enforce every crime we see,” he said. “Well, how many negative interactions do we encounter or initiate because of that strategy?”

Elliott emphasized that the center and new tech can also serve a “community caretaking” role – to help with search-and-rescue operations or find missing people. He offered a recent anecdote about an elderly dementia patient who was located in another state with the help of license-plate readers.

Surveillance skeptics might point to different examples. Late last year, a federal lawsuit revealed that sheriff’s deputies used helicopters equipped with infrared imaging to keep tabs on the number of homeless residents at Spokane’s now-dismantled Camp Hope.

Elliott himself offered “vagrancy and drug use” in public parks as an example of where the new tech might prove useful. The video analytics software can turn video footage into heat maps, he said, revealing where most park users congregate. Deputies can then focus their efforts on those individuals “rather than contacting everyone.”

The city of Spokane recently passed a law that makes being in a park after 10 p.m. a criminal act, and empowers police to arrest people if they refuse to leave.

For Dave Maass of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the likelihood that new heat maps might be employed to track homeless people in parks reflects his suspicion that enhanced tech serves primarily to incentivize frivolous policing of crimes of poverty.

“You hear from police that this technology is a force multiplier, one officer can do the work of four officers,” Maass said. “Do they need more force?”

In the absence of strong use regulations or consistent oversight, the question of whether new tech will lead to sharper police work or intensify problematic enforcement practices largely depends on the police’s ability to police themselves.

In May, Spokane County officials considered the purchase of the video analytics software linking surveillance tools in the new crime center. Democratic County Commissioner Chris Jordan told his colleagues the sheriff’s office had assured him the software’s facial recognition capability was not “part of the plan.”

“I just wanted folks to be aware,” Jordan said, “… that is a functionality that will not be used under this contract.”

No other commissioners, one other Democrat and three Republicans, offered further public discussion of the purchase. The authorization passed unanimously.

FEATURED IMAGE: Video surveillance software is shown on screens used in Spokane County Sheriff’s Office’s temporary ‘Real Time Crime Center,’ which will analyze footage from various surveillance camera feeds and other software to aid in police work. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

Visit crosscut.com/donate to support nonprofit, freely distributed, local journalism.