Portland-based NWEA suggests the new findings point to a lasting crisis in student achievement.

By Elizabeth Miller (OPB)

National education researchers say student academic progress is stalling in math and reading, a sign that students are taking longer than expected to recover from the pandemic and a warning to school leaders to put more resources into helping students.

Portland-based test developer NWEA is behind the new report out on Tuesday — the latest in a series of reports charting the pandemic’s effect on learning for millions of students nationwide.

“We had this expectation that getting kids back into the classroom was the magic bullet,” said Karyn Lewis, director of NWEA’s Center for School and Student Progress and co-author of “Education’s long COVID: 2022-2023 achievement data reveal stalled progress toward pandemic recovery.”

“What’s really playing out is, the harm from the pandemic wasn’t just the initial event, but it’s having fallout in ways that are continuing to impede students progress much like the physical realities of long COVID manifest well beyond the inciting event of having the virus.”

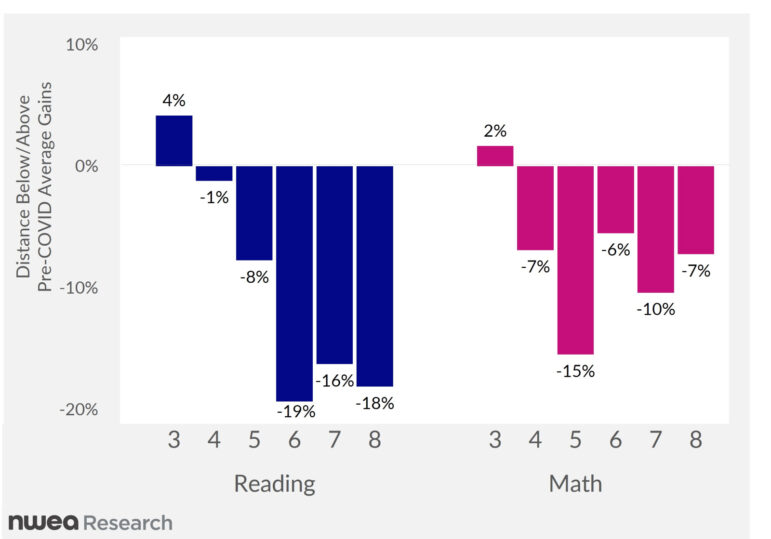

NWEA’s research shows that despite being back at school, academic progress for millions of students in grades three through eight has slowed down. While students continue to make academic gains, they are not closing consistent gaps in achievement compared to pre-pandemic levels. Some specific student groups are experiencing widening disparities.

NWEA researchers have been tracking the pandemic’s impact on academic progress since 2020. This is the ninth report the organization has released as they continue to compare the progress of 6.7 million students who have been taking NWEA tests since the pandemic began with results from 11 million students who took the tests prior to the pandemic.

Before this report, Lewis and research partner Megan Kuhfeld found students were still recovering from the years of pandemic-disrupted schooling. So by the end of the school year, Lewis and Kuhfeld had expected good news.

That good news never came.

“We were really caught off guard that that is not what panned out in the data,” Lewis said. “We find that growth for students this year actually lagged slightly behind pre-pandemic trends, which means we weren’t making additional progress towards recovery.”

Lewis said her research shows the effects of the pandemic are “compounding” — that while the pandemic may be “over”, the effect COVID-19 had on students is not. Student progress from last school year is lagging behind — both when compared with pre-pandemic levels and compared to student progress from the 2021-2022 school year.

The findings are along the same lines as other test score data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Last month, Chalkbeat reported that student scores on NAEP math and reading tests were lower than scores on the same test before the pandemic.

Part of NWEA’s report plots out what it would take to get students to pre-pandemic levels of progress by calculating how many months of “additional schooling” students would need to get there.

According to NWEA, students would need, on average, 4.5 months of math and 4.1 months of reading to catch up with their pre-pandemic counterparts. When broken down by race, Black and Latino students, especially in middle school, would need even more time. Latino middle school students would need 6.7 months of reading instruction to catch up, according to the data.

“Because Black and Hispanic students have experienced more harm from the pandemic, it will take more additional schooling to get them caught up to pre-pandemic levels of achievement,” Lewis said.

COVID recovery efforts “out of alignment with the magnitude of the crisis”

Education leaders at local, state and federal levels all knew students would have catching up to do once they returned to school in-person full-time. That’s why school districts received millions of dollars of pandemic relief funding, with a requirement to spend at least 20% of funds on academic recovery efforts.

School districts have to spend that money by September 2024. Lewis said students need more sustained support.

“There’s a wild misalignment between the actual reality of how long the road to recovery is and the access schools and districts will have to federal resources to fund those efforts,” Lewis said.

Using federal dollars, school districts have put millions into tutoring, summer programming and additional staff to help students. Lewis stressed that this data cannot answer the question of whether those efforts worked. Instead, she said, the data show schools and students need more help.

“What I think these data are telling us is that the scale of our response is out of alignment with the magnitude of our crisis,” she said.

“We need a more comprehensive, more sustained approach to recovery that can last for several years. […] It’s not just going to be high-dosage tutoring or just one summer of summer school or double-dosing math for a year. It’s going to be a layered approach of multiple interventions and multiple resources to really get us out of this spot.”

And school leaders have more than academics to worry about. Students are facing mental health challenges that schools are also tasked with addressing. Some students are struggling to even get to school, let alone progress at the same rate as students going to school before a global pandemic.

Students have been through a lot, and pre-pandemic data is one of the only ways to keep track of how current students are doing. And if schools are unable to accelerate student progress, academic gaps will continue to grow.

“I think this is another instance where we might be done with COVID, but COVID is not done with us,” Lewis said.