Attorneys say there’s little accountability for judges who may show bias against victims

By Wilson Criscione / InvestigateWest

In 2021, Marie worried that her son was unsafe at her ex-husband’s home. She went into the county courthouse in Pasco, Washington, and filed a restraining order, thinking she had a good case: There was audio of an alleged assault of her 16-year-old son, and the boy’s therapist provided written documentation.

But she says the judge that day, Samuel Swanberg, didn’t let her attorney speak. When Swanberg signed the order, he wrote “Denied!” emphatically — exclamation point and all — and circled it. Marie thought the judge was purposefully taunting her.

“I felt targeted,” said Marie, 42, who, fearing reprisal, asked to be identified only by her middle name.

Soon after, she realized something bigger might be going on. In late 2021, a woman filed for a protection order against Swanberg. That was followed by allegations of domestic violence from Swanberg’s ex-wife, resulting in criminal charges. Meanwhile, news broke that Swanberg denied a protection order against a man who would end up shooting two people at a Fred Meyer grocery store in Richland last year.

Swanberg was removed from the bench until a jury found him not guilty of domestic violence. Today, he’s back in court and able to hear protection order cases. But for victims and those who work closely with them, the allegations raised questions about Swanberg’s ability to give a fair ruling for those seeking protection from domestic violence, sexual violence, stalking or harassment.

Several women who have appeared in Swanberg’s courtroom told InvestigateWest that he unfairly denied their protection orders. Attorneys in the area are finding ways to avoid Swanberg entirely when their clients seek protection.

“I won’t have him hear any of my cases,” said Karla Carlisle, a managing attorney with Northwest Justice Project, which provides free civil legal assistance to low-income people in Washington and often represents clients seeking protection orders. “There’s no way he could be an impartial tribunal.”

People who are victims of domestic violence, sexual violence, stalking or harassment seek these orders hoping to gain legal protection from alleged abusers. A judge’s decision can help protect victims, or it can put them in danger. It can rightfully hold abusers accountable or, in some cases, wrongfully put restrictions on people based on flimsy accusations.

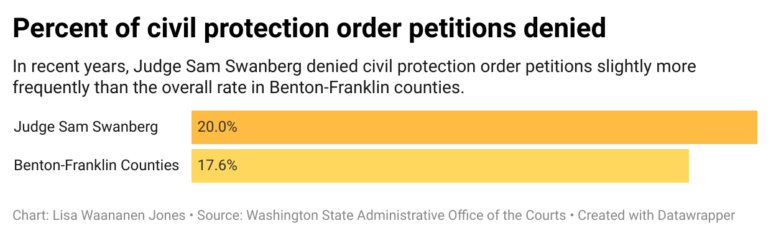

In Washington, just 17 percent of civil protection orders are denied, with some jurisdictions and judges denying at a far higher rate than others, according to data from the Administrative Office of the Courts from the last five years analyzed by InvestigateWest. That statewide data does not include King County, which uses a different system to track cases.

Swanberg denies protection orders at a rate slightly higher than state average, though he’s not a clear outlier. Still, the consequences of these orders can be life-altering.

“The power judges have is enormous in almost every case, but particularly these cases,” said Leigh Goodmark, director of the gender violence clinic at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law. “They’re often asked to make credibility calculations between two people saying different things, with the fear that if they do the wrong thing, somebody will turn up dead.”

For his part, Swanberg told InvestigateWest he’s just as fit as any other judge to make protection order rulings. He stressed that he was acquitted of the domestic violence charges and said his personal life plays no role in his rulings.

“The bottom line is that I can be fair to anyone because as a judge, my personal experiences are not what I base rulings on,” Swanberg said. “We all have experiences as a judge. You put everything in your own life aside.”

JUDGE ACCUSED

The Superior Court of Benton and Franklin Counties removed Swanberg from the bench in late 2021 when an ex-girlfriend of his filed for an anti-harassment order. They’d started dating while the woman worked at the Franklin County Clerk’s Office, but when they broke up, she accused Swanberg of harassing her at her job and, at times, threatening to end his life if she didn’t take him back. The woman, who declined to be interviewed for this story, entered a declaration saying she felt “harassed and scared” by him.

Her temporary anti-harassment order was granted, but the request for the court to take his gun was denied.

Meanwhile, as part of the case, Swanberg’s ex-wife, Stephanie Barnard — now a state representative — filed her own declaration supporting the woman. Her declaration alleged physical abuse, which prompted a criminal investigation. Barnard declined to comment for this story.

A jury later acquitted Swanberg of all charges, finding that the alleged violence was done in self-defense and that the state should repay his attorney fees and lost wages.

Still, the controversy made many women question Swanberg’s rulings in their own cases. One person took the domain for Swanberg’s former campaign website, swanbergforjudge.com, and turned it into an anti-Swanberg website that says on the homepage, “Swanberg for judge? Hell no!” On Facebook, a group of women who Swanberg ruled against in protection order cases called Swanberg’s rulings into question.

“I can’t imagine any of the cases he’s making judgments on can be valid,” Marie said. “I don’t believe he should have the right to make decisions that are life-changing for people.”

‘GUT DECISIONS’

While some advocates and attorneys in the Tri-Cities area may see Swanberg as too biased to give fair rulings on protection orders, his rate of protection order denials doesn’t stand out from other judicial officers.

Swanberg denies one in five protection orders he sees, according to data from the Administrative Office of the Courts. That’s slightly higher than the average in Benton and Franklin counties overall, at 17.6 percent.

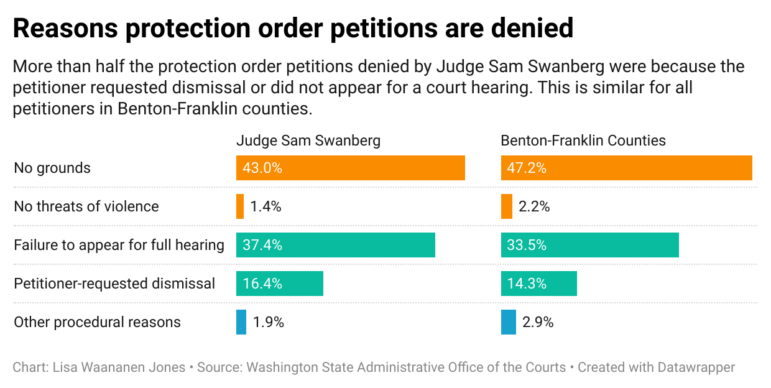

Advocates and judges said it can be hard to draw too many conclusions just from looking at how often judges deny protection orders. Certain judges may have higher denial rates based on the types of cases they hear. Many orders logged as “denied” in the court system are actually orders where the person who filed for an order decided not to move forward with the case. Initially, judges or commissioners may rule on temporary protection orders, which, if granted, would stay in place for 14 days or until a hearing for a full protection order that may be heard by a different judge. Temporary protection orders may be judged based on different criteria than full orders.

In the case of the Richland Fred Meyer shooter, an ex-roommate had requested a protection order against Aaron Christopher Kelly in October 2020, saying he saw Kelly with a 9 mm handgun. Just over a year after Swanberg denied the protection order, Kelly brought a 9 mm handgun to the Fred Meyer store and shot two people, killing one.

Deirdre Bowen, director of the family law center at Seattle University School of Law, said problems can arise when judges and commissioners are overloaded with protection orders. Without much time to spend on each case, judicial officers may rely on “gut decisions.”

“They’re relying on what the petitioner and respondent say,” Bowen said. “Who do I identify more with between these two people? And who do I think has more to lose? That can be the thought process, and it’s human nature when you aren’t looking at evidence and having a thorough evidentiary hearing.”

That may open decisions to bias. Black and Native American people, for example, are most likely to have protection orders denied in King County, according to an audit of King County’s system.

Judges are also more likely to grant petitions when the person seeking an order is assisted by an advocate or attorney. Judges, however, say it’s rare for either party in such cases to have attorneys or advocates in the courtroom for protection order hearings. That’s true in the Tri-Cities area, too, said Carlisle. Many people seeking protection orders are low-income and can’t hire expensive attorneys. The Northwest Justice Project is one of the few resources for those people to have legal representation, but “there are simply not enough” attorneys like Carlisle to meet the need, she said.

“We are severely understaffed,” Carlisle said.

Swanberg agreed that ideally everyone would have an attorney in the courtroom or an advocate assisting them. He said it helps to have someone presenting clear, accurate evidence and making relevant legal arguments.

“It would make my job as a judge easier,” Swanberg said. “I am in favor of any way to allow more people to have access to justice, to be heard and to be heard effectively.”

LACK OF OVERSIGHT

Because Marie’s initial protection order was denied by Swanberg, it was harder for her to prove to other judges that she and her son needed protection from her ex-husband, she said. The case dragged on for two years.

“It was just a constant worry for two years about what was going to happen. And every time I went to court, I looked at the docket to see who the judge was, and I thought, ‘What if it’s him again?’” she said.

In May, Marie finally won her case, which had grown beyond the original protection order. As it turned out, Swanberg made the final ruling. Still, Marie felt it was an unnecessarily difficult process given the evidence in her favor.

If someone believes a judge has a bias against them or people like them, they can file an affidavit of prejudice and have the judge removed from a case.

“People should be able to believe a judge is going to be fair to them,” Swanberg said. “Then you are entitled to get a new judge. All you have to do is sign an affidavit.”

That’s what Carlisle has been doing since Swanberg has been on the bench. In fact, Swanberg — up for re-election next year — told InvestigateWest that months after he returned, he still hadn’t heard any protection order cases. Before his temporary removal, he averaged roughly one per day, according to data from the Administrative Office of the Courts.

But filing an affidavit against a judge is a route that many survivors are not aware of. And while Superior Court judges are elected, commissioners — who also hear protection orders — are not. Beyond voting a judge out in the next election, there’s little to do about a judge who may show a pattern of ruling against women or victims of violence.

“There are no consequences, really,” Carlisle said.

Carlisle still questioned Swanberg’s ability to be impartial with protection orders. Speaking generally, while she acknowledged that every human makes mistakes, she felt judges should be held to a higher standard. If they’re not, it damages the public’s trust in the criminal justice system.

“It really eats at the institution,’ she said. “Judges should be held to a very high standard so that people have faith that they are impartial.”

FEATURED IMAGE: Benton Franklin Superior Court Judge Sam Swanberg is back on the bench after he was acquitted of domestic violence assault charges. (Bob Brawdy/Tri-City Herald)

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. This project was supported with funding from the Data-Driven Reporting Project and the Fund for Investigative Journalism. The Data-Driven Reporting Project is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University | Medill.