For parents and providers, the dollars just don’t make sense.

Despite multiple challenges, single mother Jessica Heavner thought she had her life back on track. Escaping a domestic violence situation with her three children — a baby, a toddler and a 7-year-old — Heavner found a full-time accounting job with benefits in August 2020.

But so far, she has spent 2021 worrying that she will have to quit her new job if her income makes her ineligible for the government subsidies that help with Washington’s notoriously high child care costs. And if she loses the slots her children now occupy with caregivers, even temporarily, it’s a high-stakes gamble whether she’ll find another suitable child care provider.

Heavner is one of hundreds of thousands of Washington parents confronting high child care costs and/or long waiting lists for quality care — problems arising from the providers’ impossible balancing act of offering affordable, quality care as well as good jobs that retain trained employees.

And like many of those parents, she is waiting to learn whether federal, state and local programs will find money and develop strategies to solve these problems.

Washington state was in crisis even before the coronavirus pandemic shut down schools and child care operations, exposing critical gaps in the nation’s child care system.

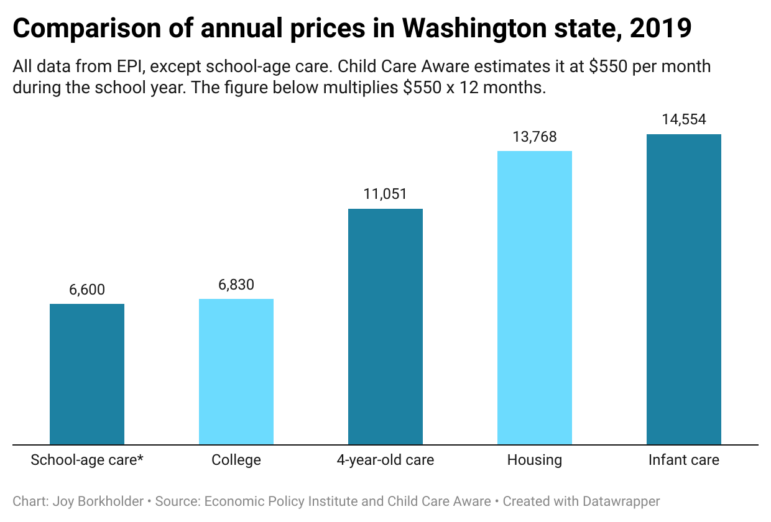

According to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), Washington ranked ninth among the least-affordable states in the nation for infant care in 2019, with costs requiring 20% of median family incomes.

Fast-forward to 2021, the crisis of child care costs and capacity not only has worsened for the most vulnerable working families, but it has continued to spread up the socioeconomic ladder to higher-income workers.

“For so many years, our society has been structured on two-parent homes, with one person available to stay home. But nowadays, it takes two parents to work to afford a home and day care and everything else,” Heavner said.

Jessica Heavner holds her 2-year-old daughter Zoey at their home in Federal Way. Facing the possible loss of her child care subsidies next year, Heavner now hopes a program like Washington state’s Fair Start for Kids will allow her to afford child care and still pay household bills each month.

(Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest)

At the same time, child care providers operate at low, sometimes negative financial margins, which means there are fewer available caregivers.

“You simply can’t charge families enough money to pay a living wage to employees. The math doesn’t work,” said Johnny Otto, executive director of Small Faces Child Development Center in Seattle’s Crown Hill neighborhood.

The state estimates that in the spring of 2020, Washington had licensed capacity to care for 41% of children from infants to age 4 years, and 5% of school-age children. That’s 185,867 slots to serve an estimated 459,000 young children. This does not account for informal care arrangements, which might cover nearly 100,000 young children.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that across the United States, many mothers of young children who left paid work in April 2020 had not returned to the workforce in November, compared with fathers, most of whom had gone back to work. Black and Hispanic mothers were more likely than other parents to not work outside the home or work fewer hours because of child care and school disruptions. And as of August 2020, while only 9% of parents reported that their child care providers had permanently closed, 62% reported that their providers were either temporarily closed or operating at reduced capacity.

The Washington State Department of Commerce reported in 2019 that employers lose an estimated $2.08 billion annually from employee turnover and missed work caused by child care disruptions. Altogether, the state economy loses $6.5 billion per year because of child care access and affordability problems affecting workers and businesses, according to an analysis conducted for the department by Eastern Washington University.

Nationally, the child care crisis cost $57 billion in 2018, according to estimates made by Ready Nation, and that price tag has likely increased.

More than ever, there is broad acknowledgement of the essential role of child care in the national economy, said Helene Stebbins of the nonprofit Alliance for Early Success, whose national network is trying to seize the moment and move quickly to support improved outcomes for children from infants to age 8.

The alliance has published a “roadmap” for both immediate and long-term solutions to galvanize system change, and it will award grants to as many as five states this summer. The grants, aimed at wholesale system change, will focus on the inclusion of diverse stakeholder voices, especially women and people of color who provide child care and who need child care.

Acknowledging the cost

Enter the Fair Start for Kids Act, passed this spring by the Washington Legislature. If implemented as planned, moms like Heavner might get to keep their jobs and homes, pay their bills and feed their children without child care costs overwhelming their families.

InvestigateWest talked to Heavner as part of an examination into the child care crisis in Washington state.

Heavner loves her new job as an accounting technician for Federal Way Public Schools, but she worries, “Will I have to quit my job? Will schools be open full-time? Will my 8-year-old have to come home after school and be alone?” The $2,950 per month she would be charged for unsubsidized, “private pay” child care for her three children would eat up well over half of her paycheck. The average price for full-time care for just her infant is more than her mortgage — a reality shared by the average Washington parent. According to an analysis by EPI, full-time infant care in Washington not only costs more than the average rent for housing, but far more than a year of in-state public college tuition.

For families with low incomes, subsidies and scholarships can fill in the gap. The state’s current programs will cover child care costs for a family of four only if its income is less than $4,416 monthly.

When Heavner’s eligibility for a subsidy was reviewed in January, she was alarmed to find out that income from her new job had pushed her slightly over the line and into the process of “phase-out.” Her copay would have jumped from $65 to $747. With current pandemic relief, however, she and other parents like her have been paying $115 per month for care.

Child care slots tough to come by

Along with prohibitive costs, parents also face the problem of accessibility: There simply are not enough child care slots available, subsidized or not.

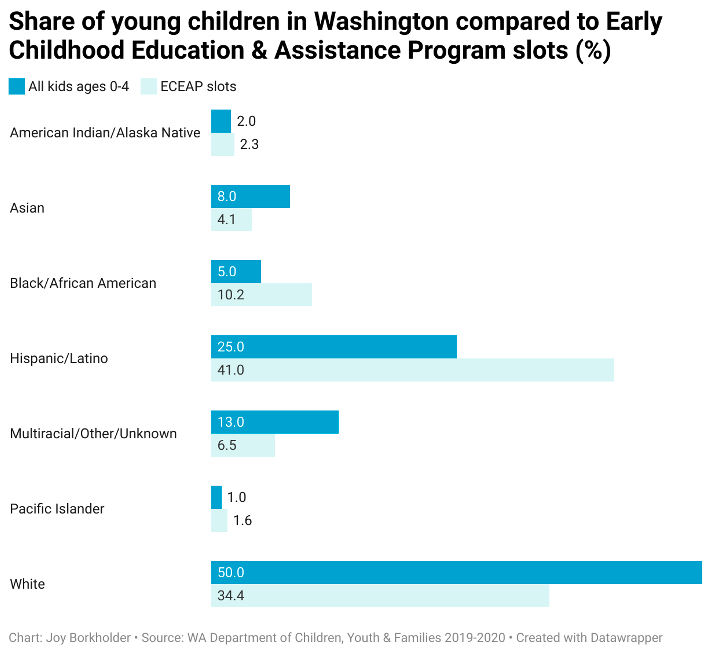

According to a 2019 survey by Elway Research, in 60% of Washington households with children younger than age 6, all available parents had paying jobs. This meant more than 300,000 children needed care. At that time, child care capacity in the state for kids from infants to age 12 was about 186,000. In Federal Way, south of Seattle, Heavner spent months on waiting lists for child care. While the need for affordable, accessible child care is broad, children of color are in particular need of support. They make up 50% of kids younger than school age in Washington, but they comprise about 65% of kids who participate in subsidized child care and in the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program, which is government-provided preschool.

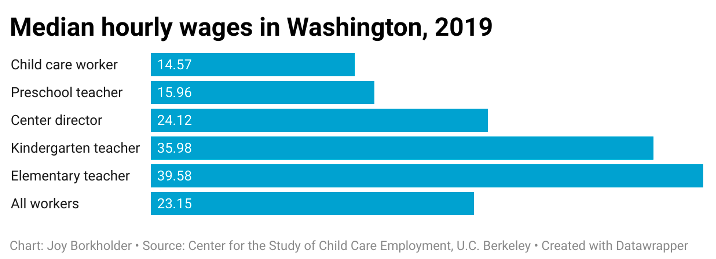

At the same time, child care workers are barely scraping by. The state’s Compensation Technical Working Group found that wages for early childhood educators rank in the lowest 3% of all jobs, with 39% of caregivers needing at least one form of public assistance. Child care providers say that even unsubsidized rates barely cover their business expenses, and subsidy rates fall far short of market rates. This financial squeeze translates to low wages and minimal benefits for child care workers, a group that is 94% women, 50% people of color and 30% bilingual or multilingual.

At the same time, child care workers are barely scraping by. The state’s Compensation Technical Working Group found that wages for early childhood educators rank in the lowest 3% of all jobs, with 39% of caregivers needing at least one form of public assistance. Child care providers say that even unsubsidized rates barely cover their business expenses, and subsidy rates fall far short of market rates. This financial squeeze translates to low wages and minimal benefits for child care workers, a group that is 94% women, 50% people of color and 30% bilingual or multilingual.

Turnover is 43% among Washington’s early learning teachers, an expense that has a significant impact on providers’ bottom lines and on the important bond between caregivers and children. Angie Hicks-Maxie, CEO of Tiny Tots Development Center in South Seattle, said that she sees her staff members study for degrees and credentials and then move on to higher-paying jobs with better benefits in school districts.

Turnover is 43% among Washington’s early learning teachers, an expense that has a significant impact on providers’ bottom lines and on the important bond between caregivers and children. Angie Hicks-Maxie, CEO of Tiny Tots Development Center in South Seattle, said that she sees her staff members study for degrees and credentials and then move on to higher-paying jobs with better benefits in school districts.

“It bothers me to my core, that the reason we can do the work we do is because we undervalue our teachers,” Hicks-Maxie said.

She and Otto are part of a new coalition of Seattle child care providers who asked the city to use some of its federal pandemic relief money on child care workers by funding the equivalent of a $2-per-hour raise for the second half of 2021. On June 21, the City Council approved an increase of $1-per-hour.

Johnny Otto, executive director of Small Faces Child Development Center, is part of a coalition of Seattle child care providers asking the city to use federal pandemic relief money to fund the equivalent of a $2-per-hour raise for child care workers in the second half of 2021. (Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest)

Even before state quarantine orders shut down schools and day care centers in 2020, a survey found 49% of Washington parents were having a difficult or very difficult time finding, affording and keeping child care. And this lack of child care affected parents’ economic opportunities. More than 1 in 4 parents quit their job or left school because of child care issues, and another 1 in 4 cut back from full-time to part-time work.

Quarantine orders made the situation worse as parents struggled to both work and care for their children. In a May 2020 survey of Washington parents, 18% said that they had turned down a job offer or promotion because of child care issues. And 47% of unemployed parents (51% of women and 41% of men) said child care issues were a barrier to finding another job.

And this isn’t a problem found only in areas with high costs of living. Before 2020, parents waited for at least a year for infant slots and 10 months for preschool slots at Spokane’s Journey Discovery Center. The center again has a long waiting list, with more than 119 families now looking at about a one-year wait for an infant, toddler or preschooler opening.

In Washington, about 161,000 children from infants to age 5 live in a “child care desert,” defined as a location with inadequate licensed child care capacity within a 20-minute drive from home. In 15 counties, ranging from Whatcom to Benton, more than half of families with young children live in such deserts. Parents across the state would like for about 48,000 of those 161,000 children to be in a licensed center or home. Additionally, 1 in 4 parents need child care outside of traditional hours, while fewer than 1 in 10 child care slots are with providers who offer evening, overnight or weekend hours.

“We have 20 years of data on brain development in young children and the science of the brain, but we haven’t settled how we support it,” said Stebbins of the Alliance for Early Success.

A path forward

State legislators, child care providers and advocates have worked toward improving this system for decades. The state Child Care Collaborative Task Force was already well into its work plan before 2020. Informed by the task force’s work and that of other stakeholders, the Legislature this spring passed the Fair Start for Kids Act, along with a capital gains tax to fund parts of it once federal relief dollars run out. The tax would net an estimated $445 million in fiscal year 2023 if it withstands the legal challenges recently filed against it.

At the Fair Start bill signing on May 7, Gov. Jay Inslee and others called it “historic,” noting that it is the largest investment in early learning in Washington state’s history.

“We also know that child care is not something that’s a poverty program. It’s an economic recovery program,” said Sen. Claire Wilson, D-Auburn, a key sponsor of the bill and a member of the task force. “There is no family that I know that doesn’t need some kind of support. And this Fair Start for Kids does that.”

Jessica Heavner with her children Alexia, 7, and Joseph, 3, at their home in Federal Way. Heavner has worried that her new job as an accounting technician could make her ineligible for reduced child care costs. (Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest)

Fair Start expands income eligibility for both Working Connections Child Care and Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program recipients. And among the many changes the law makes, it increases subsidies paid to providers. Its success hinges on various provisions in the bill that are intended to increase system supply to meet the demand.

The final estimate of additional uptake in Working Connections Child Care subsidies is not yet available. However, the program’s January 2021 family caseload was about 14,000 below the cap of 33,000. Enrollment in the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program would nearly double from the current 14,662 funded slots to 28,723 in 2027, when it becomes an entitlement.

If nothing had changed, come January 2022, Heavner would not have been eligible for any subsidies. After paying child care, health insurance and her mortgage, she would have no money left for other bills every month. “I am so happy that our legislators made Fair Start for Kids happen, but it made me sad that a pandemic had to happen for people to realize what a problem this is,” Heavner said.

Feature image: As her 2-year-old Zoey enjoys a picture book, Jessica Heavner throws a Frisbee with her son Joseph, 3, and daughter Alexia, 7, at their home in Federal Way. Heavner said she spent months on waiting lists for child care in Federal Way. (Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest)

A note to our readers:

Our country has long faced sprawling social and economic challenges stemming from a crisis in child care, with problems ranging from high costs of care and limited availability to low wages for those working in the field. A new in-depth reporting series by InvestigateWest journalists will explore the root causes of these issues as they continue to shape life in Washington state, and dive deep to illuminate potential solutions.

What do you want to know about child care? Submit your questions here and we’ll dig for answers over the course of our reporting.