Emily Lorenzen knows her story of being sexually assaulted is a difficult one for people to hear. The petite 22-year-old isn’t bothered. She knows her listeners don’t know what to say.

But they need to hear her words. It’s a story that has helped remake Oregon’s response to sexual assault on public university campuses and could galvanize reform at other colleges and universities throughout the Northwest.

Lorenzen’s father is a former president of the Oregon State Board of Higher Education, and the chair of a subcommittee slated with retooling policy on how state schools respond to assault. In addition to strengthening state schools’ definition of sexual assault, the Oregon subcommittee is looking at tougher discipline for students who commit sexual assault, and widening school jurisdictions to handle assaults that take place off campus.

A dad first, Henry Lorenzen is motivated. Four years after his daughter reported being raped while a student at the University of California at Berkeley, Lorenzen doesn’t want what happened to her to happen to students in Oregon or elsewhere. And it isn’t only the thought of the rape that haunts him. It’s what he sees as the lackluster investigation, the lack of sympathy, the lack of resources, and the disbelief with which Berkeley officials greeted his daughter that most trouble him.

Berkeley officials say they are not indifferent to sexual assault, citing a range of campus programs intended to support rape victims.

Arguing for a firmer definition of campus sexual assault at a Board of Higher Education meeting on Dec. 22, Henry Lorenzen blows the bureaucratic slumber out of the room. When he says that his daughter was raped at college, people stop shuffling papers. They look up. They sit straighter. They listen.

Lorenzen doesn’t tell the whole story. But he tells enough to keep policy moving forward. The full story – a more personal story – is for his daughter to tell. It’s a troubling story, similar to the stories told by many young women at colleges and universities across America.

One in Five Women Assaulted

Disturbingly little has changed when it comes to sexual assaults on campuses. People still blame the victims. Victims still blame themselves. While there are more groups on campuses devoted to assisting assault victims, they still help only a fraction of those who actually experience assaults. One in five will experience rape or attempted rape in their four-year college term, according to a 2000 report funded by the U.S. Department of Justice.

“I don’t think general attitudes about sexual assault have changed in the 30 years I’ve been doing it,” said Rebecca Roe, Seattle-based attorney who specializes in sexual assault cases. “It’s very, very depressing.”

“College-age women are at very high risk for sexual violence,” said Adam Shipman, director of education and advocacy for the Sexual Assault and Family Trauma Response Center in Spokane, which sees students from Washington State University, Eastern Washington University, and Gonzaga University. Many are away from home and in dating relationships for the first time. They are experimenting with new, sometimes risky behavior, such as drinking and drugs, as they test their independence.

That activity, combined with lack of understanding about definitions of consent, makes them vulnerable to non-consensual sex, he said. “It’s more common than we like to think.”

Culture of Denial

Emily Lorenzen was from a small town in Oregon and a member of a University of California athletic club, going away for a training weekend early in her first year at college. Here’s what she remembers: A persistent upperclassman whose sexual advances she had earlier spurned, joined by other members of the club, pressured her into drinking too much alcohol and taking off her clothes. She did.

Her father thinks it’s fortunate that Emily doesn’t remember what happened next. She does remember waking up the following morning in a bed next to the man she previously rejected. She was naked except for her bra. And her vagina hurt. Her worst suspicion was confirmed the following day, when the party-minded club, turned the sexual assault into another drinking game, she recalls.

“I knew when I woke up. But I knew for sure when somebody said I had to take a shot because I had sex,” she said. It would be four months before she told her parents what happened. It would be four months before she could admit it, even to herself.

Part of the ongoing issue with sexual assault and date rape is the frequent delay in reporting, and part of that is the lack of training for students to recognize and be aware of the crime. The shock that overtook Emily Lorenzen, for example, is typical, and such delays complicate investigations when allegations are made. There is also a persistent cultural denial about college rape.

Jessica Mindlin  is the National Director of Training and Technical Assistance for the Victim Rights Law Center (VRLC), a non-profit organization dedicated to transforming the nation’s legal response to sexual assault. She is based in the center’s satellite office in Portland, where she monitors outcomes in sexual assault cases at colleges and policies surrounding campus assault. “What we see happening at the university level is kind of a microcosm of what we encounter in larger society, which is that it makes everybody uncomfortable to talk about nonconsensual sexual contact, about sexual assault,” she said. “So what we find is that they would rather characterize it as a ‘misunderstanding.’”

is the National Director of Training and Technical Assistance for the Victim Rights Law Center (VRLC), a non-profit organization dedicated to transforming the nation’s legal response to sexual assault. She is based in the center’s satellite office in Portland, where she monitors outcomes in sexual assault cases at colleges and policies surrounding campus assault. “What we see happening at the university level is kind of a microcosm of what we encounter in larger society, which is that it makes everybody uncomfortable to talk about nonconsensual sexual contact, about sexual assault,” she said. “So what we find is that they would rather characterize it as a ‘misunderstanding.’”

Young men, in particular, are ill-informed about what constitutes consensual sex. They are steeped in a “Girls Gone Wild” and “Spring break” culture that glorifies the drunken sexual bacchanal. Getting drunk and having sex are pretty standard plot fare in movies aimed at young men, said Shipman. “It’s a standard way young men are socialized.”

Alcohol is a factor in at least half of date rapes, said experts who handle sexual assault cases. Many college-age men simply don’t understand that if they have sex with a woman who is too drunk to consent, they are committing a rape. And many college-age women may not understand they have a right to report it, or they’re afraid.

Stephanie S., who didn’t want to use her last name, said she was assaulted as a freshman by an athlete at the University of Washington. She says she initially didn’t report the assault because she was unsure and in shock. Stephanie eventually became trained as a peer counselor for other college rape victims. Surveys show that many women answer, “no” when asked if they’ve been raped, she said. But they will answer in the affirmative if asked a different way, using “lesser language,” such as, “Have you ever been coerced, forced or done something against your will?”

Other students don’t come forward because they know it will invite an attack on their own reputations, or credibility. Stephanie said she was urged to “not make a scene” and avoid “behavior that would put a bad light on the football team or athletic department.”

Her apartment was vandalized the day she filed a lawsuit against the university for its handling of her case.

Perhaps the biggest deterrent to reporting, however, is self-blame. “They think that if they went out to a party, and were drinking, they were somehow to blame for what happened,” said Shipman. “They need to understand they are the victim of a crime.”

A Greater Injustic

After Lorenzen told her family about her experience, they all thought the worst of the ordeal was behind them. They now believe that the injustice she suffered when she reported that she was raped to a campus safety officer at Berkeley was greater than the actual assault.

The officer told her that she should not have been drinking, and then launched a cursory investigation by sending letters to the club members, asking them to come to his office for an interview. They got their stories straight, she said. “I just wanted something to happen… Either the guy getting punished or Berkeley having to change its ways,” Lorenzen said. But no consequence came.

Following pressure from the Lorenzen family, Berkeley stopped recognizing the club as an official student organization, but the student Lorenzen accused of raping her was not disciplined, nor were students who concealed the truth. Those students’ lives moved on. And for a long while Emily’s did not.

Berkeley officials declined to comment on Lorenzen’s case, citing student privacy laws. Janet Gilmore, a spokesperson for the university, said Berkeley has a trained team of professionals that reviews sexual assault cases and provides support services to victims. She added that Berkeley is “always looking at ways to strengthen and improve the experience for students that report to us” and would review the Oregon University System’s new policies.

In Lorenzen’s case, however, Berkeley’s professional committee declined to consider student conduct charges or hold a full student conduct hearing in her case, citing lack of evidence. Though Lorenzen repeatedly requested to attend the meeting, she was not invited, she said.

Henry Lorenzen, a lawyer and former assistant U.S. attorney, says he knows the difference between a quality process and a legal defense. He felt Berkeley offered only empty process to his daughter. “They wanted to protect the university more than have a process that worked well both for the victim and the accused,” he said.

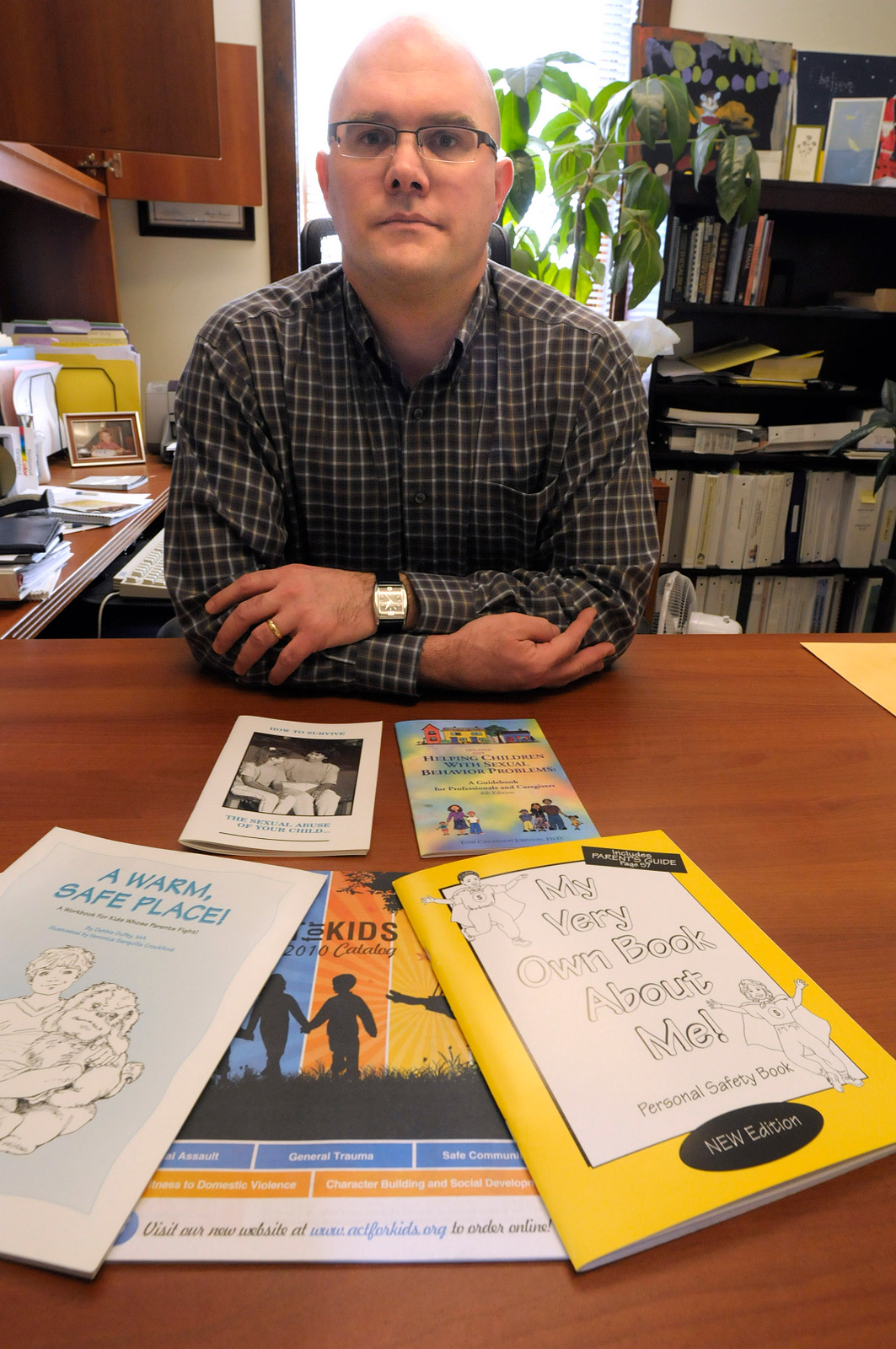

Henry Lorenzen was president of the Oregon State Board of Higher Education at the time. His last order of business, shortly after the rape, was to create a Subcommittee on Sexual Assault to retool the Oregon University System’s policies into a model of best practices. He appointed himself to the subcommittee, and now is its chair. The subcommittee represents the seven schools that make up the Oregon University System. It includes members who are particularly familiar with sexual assault policy, including Jonathan Eldridge from Southern Oregon University, whose work while at Lewis & Clark College has been nationally recognized. Eldridge was instrumental in galvanizing this effort to reshape public universities’ policies.

With Henry Lorenzen as its chair, the subcommittee first created an enforceable definition of the crime, which was approved by the Oregon Board of Education Dec. 22 after two years of work. The definition was retooled to fit more with life on campus than the Oregon criminal code, which lessens penalties for sex crimes that don’t involve male penetration. For example, stalking a victim is not okay by state law or on campus in Oregon, but the campus definition goes further and includes hanging out in places where the perpetrator knows the victim is likely to be as within the definition of stalking, for example. Videotaping and audiotaping sex without consent is included in the definition of sexual misconduct.

The upshot – the university system is trying to find ways to discipline students for behavior that is clearly threatening but in a gray area of the law. Lorenzen now wants to make it harder for perpetrators of sexual assault to hide behind federal laws that protect student privacy. And he doesn’t want administrators to lessen penalties for perpetrators to avoid lawsuits. He believes stiffer penalties will create a culture in which male students will understand that sex crimes are “not only not appropriate, but deeply reprehensible.”

He wants the university system to go even further – taking jurisdiction of students who commit crimes off campus, investigating sexual assaults using law enforcement techniques and retired police officers, and creating a centralized student conduct board that can hold off-campus conduct hearings and appeals for sexual assault cases, if a victim chooses to pursue discipline for an attacker but wants more privacy than an on-campus proceeding would allow.

New Solutions

Universities are beginning to tackle the issue of sexual assault in a number of ways, including surveying students to get a better handle on numbers, and increasing their emphasis on prevention. In particular, a growing number of schools have begun addressing the underlying cultural issues through training and “bystander involvement” campaigns.

Washington, for example, is among the first to implement a program called “Green Dot” at campuses across the state, said Melissa Tumas, director of the Sexual Assault and Relationship Violence Information Center at the University of Washington. The Green Dot campaign, modeled on one started in Kentucky, is a way to promote positive behavior that stops sexual violence from occurring. In addition to mounting training programs to raise awareness, schools post maps with red dots marking spots where there have been reports of assaults, and green dots marking spots where someone intervened to prevent a potentially dangerous situation.

“It’s a shift in the way of thinking,” said Barbara Maxwell, associate dean of students at Whitman College, one of the first schools to launch the program. “It tries to be as gender-neutral as possible,” she said. “A lot of programs used to make male students feel defensive, like we were pointing the finger at them. This program pulls in anybody to be a proactive bystander.”

“It’s a shift in the way of thinking,” said Barbara Maxwell, associate dean of students at Whitman College, one of the first schools to launch the program. “It tries to be as gender-neutral as possible,” she said. “A lot of programs used to make male students feel defensive, like we were pointing the finger at them. This program pulls in anybody to be a proactive bystander.”

Whitman College and Central Washington University were the first to launch campaigns in this state. Eastern Washington, University of Washington, Pacific Lutheran University are also nearing launch, and Gonzaga University and the University of Puget Sound are interested as well, said Maxwell, who is also co-chair of the Washington Sexual Violence Prevention College Coalition.

Bystander campaigns can be effective because they don’t necessarily require confrontational behavior, said Shipman of the Spokane sexual assault center. For example, a person who observes a guy hitting on a woman who has had too much to drink can “intervene” by telling the guy his truck is being towed – something to disrupt the moment, as opposed to confronting him, said Shipman. “Sometimes the window to intervene is just 30 seconds to a minute, but that can make all the difference.”

Eldridge, vice president for student affairs at Southern Oregon University believes sexual assault education should not only target women – telling them the ways to avoid assault – but also target men. “We have to be speaking a lot more of the time with men, talking about responsibility and consequences to actions, and appropriate behavior,” Eldridge said.

Shipman agrees. He is one of only two male, professional sexual assault counselors in Washington. “Men don’t see this as our issue,” he said. “But it is.”

Attitude Adjustment

To really reduce the incidence of campus sexual assault, however, will take an attitude adjustment. There needs to be a cultural shift to be more supportive of victims, said Shipman. “Rather than asking her what she was doing, what she was wearing and why she was out late at night, we should be asking why we have a culture where so many sexual assaults still occur.”

Schools need a better process for students who pursue their attackers through school disciplinary hearings, advocates say. The Washington Sexual Violence Prevention College Coalition got together because they wanted to focus on prevention first, said co-chair Maxwell. But she added the group will likely look at developing “best practices” guidelines for school hearings in the future.

“I think one of the things we consistently find is that no matter how good it looks on paper, all too often it’s at best an unproductive process and at worst a devastating process for victims,” said Mindlin of the Victim Rights Center. Effective conduct proceedings can have a very real impact not only on the healing process, but on a victim’s ability to achieve lifetime personal and financial goals. “When victims drop out of school and don’t achieve the level of education that they would have because of sexual assault, it has a very real impact on their life,” she said.

Roe, the Seattle attorney who has represented a number of campus sexual assault victims, said the most effective thing a school can do is dedicate and train a team to handle all sexual assault allegations brought by students. “In a perfect system you’d have sexual assault allegations all handled by a specific organization on campus,” she said. “And everybody’s case should be required to go to that particular group so all cases are considered and processed by competent people in a consistent way.”

Advocates also say that training is key for students – especially incoming freshman — to better understand their rights, and know where to go if they are assaulted. “It’s very rare that someone in a situation like mine would even know that a resource existed,” said Stephanie, who didn’t know where to turn for many months and now uses her experience to counsel other women.

‘It Happened to My Daughter’

In the meantime, the Lorenzens continue to share their story. “Being able to relay it personally has given me more credibility,” Henry Lorenzen said. And as he tells people about his daughter, “It seems like 50 percent say it happened to my daughter, it happened to my friend’s daughter, it happened to a friend of mine.”

Emily Lorenzen believes that if people hear her story, they will be comfortable confronting the issue of sexual assault on campus. She wants more conversation, so that men get a clearer definition of rape, face stiffer penalties if they ignore it and administrators learn to reach out to women like her and show compassion. She especially wants bystanders to step up and protect people who are vulnerable.

On a more personal level, however, she has moved on, transferring to a private college in Portland to finish her degree. She knows that there are still good guys in the world. And she counts her father as one of them. “It makes me feel good,” she said about his efforts to change the Oregon system. “It may not be justice for this particular guy, but hopefully it will translate into another girl having a better experience.”

InvestigateWest is a non-profit investigative news organization covering the environment, health and social justice.