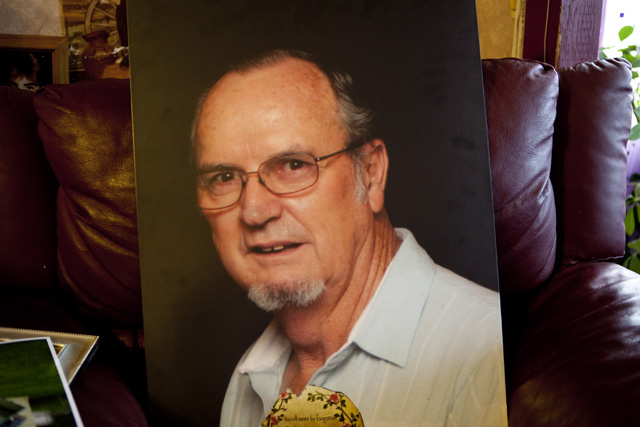

Credit: Christopher Sherlock/KCTS 9

On the afternoon of November 23, 2012, Sam Counts left his home on East Ninth Avenue in Spokane Valley to pick up bread from the grocery store. Simple enough. He had just gotten back from Christmas shopping with his wife of 45 years, now also his full-time caretaker. Counts, 71, had been diagnosed with dementia less than a year earlier. Hanging onto normalcy before the disease progressed further, Sam’s daughter Sue Belote would visit him several times a week, and he would still call her on the phone, she says. Sam’s doctor had said it was OK to drive, as long as someone else was in the car. On this Friday, Sam got into his white 2012 Kia SUV alone.

“It’ll only take me a minute. I won’t be gone long,” he told his wife, Donna Counts. Before Sam’s diagnosis, this would have been routine.

No longer.

After two hours Donna called her daughter, worried. “I don’t know what to do. Dad didn’t come back and he never stays away this long,” she said. Three hours after he left, the family reported Sam Counts missing.

The next morning, Saturday, radio and television outlets reported versions of the same story: a local man missing, trim, six feet tall, last seen in a red-and-black jacket, jeans and white tennis shoes. A description of a car and its license plate number was included.

At 9:28 a.m. KHQ Local News posted an update online:

There was a possible sighting of Sam at a Dollar Store in Argonne Village on Saturday morning. An employee there said a man matching Sam’s description walked in and seemed disoriented. A manager at McDonald’s believes she saw him on Sullivan. Sam’s family thinks it is possible that he got separated from his car.

Over seven frantic days, with the help of the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office, friends and family led a search that spanned parts of three states. They enlisted the help of a family friend who worked for the Spokane transit system to flyer local buses, and former colleagues of Counts in the postal service put up missing person photos in post offices. In the meantime, the family faced public criticism. Why was he allowed to get into the car alone? Why didn’t he have a cell phone?

“He’d been to the bread store a million times,” Donna counts told InvestigateWest in a recent interview. She took a deep breath.

“I shouldn’t have let him go.”

Wandering behavior has become increasingly familiar. Yet Washington is not prepared to deal with this emerging public health threat. Few police departments have policies or training to educate officers on Alzheimer’s or dementia. An Amber Alert-like system set up in 2009 to help find wandering people is underused, its coordinator acknowledges, and bills to create a formal Silver Alert system like those in more than 20 other states foundered in both houses of the state Legislature this year. Washington is also one of just six states that haven’t even started work on a statewide Alzheimer’s plan, even as the population at risk of wandering surges.

The current approach to safeguarding wanderers sometimes falls short, with fatal effect.

Growing numbers at risk

Over the last five years, at least ten people from Washington have died as a direct result of wandering, seven in the last 16 months, according to an analysis of media reports by InvestigateWest and interviews with law enforcement. The exact number is unknown; no public record is routinely created when wandering is a contributing factor to death, and no state agency keeps such a tally.

Most recently:

- Last September, a 79-year-old man with dementia went missing by car from an independent living facility in Seattle. He stopped at a gas station in Oakland, Ore., five hours south of Seattle, and a month later was found deceased on a logging road in the Willamette Valley.

- In October, an 80-year-old man was missing for 45 days before his body was found at the bottom of an embankment less than half a mile from the Sedro-Wooley memory care center he had wandered away from. Search and rescue volunteers from Skagit and Snohomish counties, using horses, dogs, helicopters, thermal cameras, boats and hydroplanes, had not found him before the official search was called off.

- In January, a 76-year-old man in Ronald, Wash., near Cle Elum, was found in a snow bank less than 12 hours after he was reported missing. He was taken by ambulance to the hospital, where he died from exposure.

- Later that month, neighbors in Anacortes reported an elderly man missing after they had not seen him for several days. After days of searching by the local police department, his body was found in a wooded, wetland area not far from where he lived.

Over the same five-year period, at least 33 Washington residents with dementia who wandered have been found safe, according to news media reports. In each of those cases, law enforcement became involved either as a result of a missing persons report filed by family or a caretaker or when alerted to unusual behavior by a member of the public. King County Search and Rescue has responded to 10 cases involving Alzheimer’s or dementia since the start of 2012, all of which ended safely. Countless other cases are not reported to the police, not reported in the media, or both, according to experts.

There is no mandatory waiting period to report endangered adults as missing. That can happen in the first hour that a dementia sufferer is missing, authorities say.

The number of people at risk is increasing. In 2010, 110,000 people aged 65 and older with Alzheimer’s lived in Washington, a 33 percent jump since 2000. By 2025, the Alzheimer’s Association expects there to be 150,000. And six in 10 Alzheimer’s patients will wander.

The question that a growing coalition of search and rescue professionals, caregivers, and policymakers across the nation face is this: How do we stop people with Alzheimer’s or dementia from going missing — and how do we design systems to bring them home safely when they do?

It was more than a year before Sam Counts went missing when his family first started to worry that something might be wrong. They started noticing changes, like how he’d no longer push his grandchildren on the tire swing hung from a tree outside the house when they called for him. He was increasingly forgetful.

“I thought Sam was being kind of silly about things,” his wife Donna says. “I’d laugh at him, and he’d laugh too. Until finally I thought, no, this isn’t right.”

Even so, doctors were slow to make a diagnosis. That didn’t happen until one of Counts’ daughters, a registered nurse, flew out to Washington to stay with her parents for a week, keeping a daily journal of his behavior. Soon after, Counts was put on a drug regimen to try to slow the loss of memory that had been carefully documented in the notebook his daughter gave to the doctor.

“Maybe that’s what changed (the doctor’s) mind, I don’t know,” Sue says. But she remembers clearly her mother’s phone call when the dementia diagnosis was official. “I just was devastated. As soon as you hear the word, like cancer, it’s like everything flashes through your mind what your loved one is going to experience.”

“How can you help them?” she says.

The science behind Alzheimer’s disease and dementia, which is a symptom of Alzheimer’s but can also be caused by a host of other maladies or injuries to the brain, is still emerging. There is no cure for Alzheimer’s; there’s not even a surefire way to slow its progression.

The most common type of the disease appears to start in a part of the brain called the temporal lobe, up above the ear, says Dr. Kristoffer Rhoads, a neuropsychologist and memory specialist at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, as he rotates a plastic model of a human brain in his hands.

He points to the hippocampus. “In here is a critical piece for new learning and memory, especially short-term memory,” he says. “In the early stages of the disease, the structures are still there, but they’re not running well.”

As the disease progresses and more parts of the brain begin to atrophy, patients may lose the ability to perform more complex day-to-day tasks like driving. Medium-term memory can be affected, essentially taking individuals back in time to where their only memories are of homes and workplaces from years and even decades earlier.

This is precisely where medical research has helped spark new ideas about public safety.

“Often they’re going to where they used to live, or perhaps where they used to work,” says Chris Long, the state’s search and rescue coordinator. “They have some destination in mind.”

On foot, wanderers tend to stay in the community, and most are found near where they were last seen. Seventy-five percent are found within 1.2 miles in flat, temperate areas such as Eastern Washington, and half are found within half a mile, according to Robert Koester, author of Lost Person Behavior and a speaker at the most recent state search and rescue conference. If someone with dementia gets stuck while wandering, or encounters an obstacle, he is likely to sit down and end up hidden away. When a vehicle is involved, the search radius immediately grows, but there is still an intended destination in most cases.

“Their characteristics are very predictable, in a bad way,” says Dr. Meredeth Rowe, a professor at the University of South Florida College of Nursing. Wanderers aren’t able to seek out help when they are lost. They won’t answer when their name is called. They can’t tell if they are too cold, too hot, or need a drink of water.

“It makes them a particularly hard group to find,” Rowe says.

The weekend before the shopping trip for Christmas gifts and Sam Counts’ decision to go back out for bread, Sue Belote took her parents out to dinner and a play. Sam knew all the songs and was singing along. By all outward appearances, he was doing well. It would be easy to believe he could drive to a store he’d visited dozens of times just down the road from his house and get back safely.

“I had in mind, we had a great time, Dad’s getting better,” Sue says. “Well that’s ignorance. He wasn’t doing better.”

Search and rescue

Steve Wright is career police. Until he retired last year, he was the operations commander in Vail, Colo., where among other duties he managed search and rescue in one of the toughest spots in the country to do so. And he has come face-to-face with Alzheimer’s. His mother-in-law had the disease before she passed away, and living nearby, he, his wife and his daughter all became caregivers.

“It’s a hard, hard row to hoe,” he says.

In early May of this year he was invited to the Oregon Public Safety Academy in Salem to work with some four dozen police officers and first responders from Oregon and Washington. The goal was to convey just enough information about Alzheimer’s so that when those in the room encounter it on the job — and it’s only a matter of time until they do, he told them — they can react appropriately.

Wright sketched out a timeline of the life of Larry, a hypothetical ex-police chief with Alzheimer’s, from birth through college, kids, a divorce, and retirement. “He starts to not remember his grandkids,” Wright says, erasing their names from the whiteboard. Then retirement gets erased. “He still thinks in his mind he’s a police officer.”

He can still drive. “But he may get in the car, drive 300 miles, and not know where he is when he arrives.”

Wright shared stories of his own mother-in-law, who remembered living with her husband at a military base in Alaska even as she would forget to eat and once ran off the Meals on Wheels driver with a meat fork.

“Laugh, that one’s funny,” Wright urged his audience as he recounted his mother-in-law’s escapade.

Soon Wright ventured into wandering:

“Sixty percent of Alzheimer’s patients who wander, if not found within 24 hours, are going to die. Eighty percent if not found within 72 hours are going to die.”

“I don’t know how to say it any plainer than that.”

Steve Wright travels around the country leading workshops on Alzheimer’s

for law enforcement and first responders.

Credit: Jason Alcorn/InvestigateWest

Remarkably, just half a decade ago little of this was being talked about outside of search and rescue circles. The Alzheimer’s Initiatives program, which organized the recent training in Salem — the first of its kind in the Northwest — launched in 2009 under the International Association of Chiefs of Police with support from the U.S. Department of Justice. Its purpose is to educate police and other first responders in how to protect and serve people with Alzheimer’s and dementia, including wanderers.

“The training and preparedness of law enforcement agencies is all over the map,” says Amanda Burstein, the Alzheimer’s Initiatives project manager. Some of the departments she’s worked with, in states like Florida, Virginia and Indiana where training is available or even mandated, have been aware of the wandering issue for years. Others, she says, will come to her after an “incident,” spurred to learn more after a bad encounter with Alzheimer’s.

“It’s the departments that aren’t reaching out to us that we really need to be more cognizant of and start doing some proactive outreach to,” Burstein says.

The most urgent recommendation by the Alzheimer’s Initiatives is for police departments to develop a written policy on Alzheimer’s and dementia. The group offers a model to police departments and sheriff’s offices that can lead to better and more consistent practices, even if each case remains unique.

“There are characteristics of a wanderer when dementia is in play versus” — Burstein uses air-quotes here — “a typical missing persons incident.”

In interviews with police departments and sheriff’s offices in Washington that have had a wanderer die or go missing in the last two years, InvestigateWest found just a handful are aware of this distinction, and only one — the Anacortes Police Department — reported having formal training on wandering behavior. Others acknowledged the need to do better.

The Yakima County Sheriff’s Office keeps a copy of Lost Person Behavior, Koester’s search and rescue manual. The Sheriff’s Office doesn’t have a specific policy or procedure in place for wandering, said Sgt. George Town, search and rescue coordinator for the county, but informally he follows the book’s guidance: “These are folks that can be in imminent danger, they need to get found and get back pretty soon.”

“To us the diagnosis makes no difference,” Auburn Police Department Commander Mike Hirman told InvestigateWest in April. When asked about the Alzheimer’s Initiatives program, Hirman wasn’t aware of it but invited a patrol briefing or training for his officers. “We’d be open to understanding the characteristics of dementia patients. That would be helpful to know,” he said.

At the training center in Salem, Wright set up a wandering scenario, and the trainees huddled in groups of eight and ten to sketch out a response. Set up a three to four mile perimeter. Start a block search and hit any leads. Check waterways. We can have eight to 12 deputies on scene in 20 minutes. A group asked to brainstorm outreach suggested using radio, TV and especially social media to get the word out.

Only one hand in 40 went up when Wright asked which departments already had a policy specific to dementia. It was an Oregon agency that had a female Alzheimer’s patient go missing in its jurisdiction. She died when she wasn’t found within 24 hours.

Wright repeated the call for a written policy, and added his own twist.

“I encourage you to invoke one of these because there’s a high likelihood if someone’s found 100 yards away after searching the whole county, it kind of makes your organization look a little goofy.”

The search in Spokane

By Sunday, three days after he disappeared, Sam Counts had still not been found, and the police had no leads. The handful of calls from the public about a white SUV had turned up nothing.

“We were devoting every resource that we possibly could with the information that we had to try to locate Mr. Counts,” says Chamberlin, the Spokane sheriff’s deputy.

Chamberlin and other officers had talked with Sam’s wife, Donna, and daughter, Sue, several times since the initial report was taken on Friday night. They knew he had dementia. They knew he got disoriented on occasion but also that he’d never disappeared like this before. They knew Sam had spent most of his adult life in a town called Elk, almost an hour’s drive north.

The license plate and registration number of Sam’s Kia were put into a police database. When a wanderer is driving, the first and often best hope is that some law enforcement agency, somewhere, comes across the vehicle. The sheriff’s office also issued what’s known as a “be on the lookout,” or BOLO, alert.

“Our patrol units, they’re the ones out and about beating the street,” Chamberlin says. Officers cased parking garages, apartment buildings and other locations when they weren’t responding to calls, in hopes of stumbling across Sam or his white SUV.

This is standard law enforcement response to a missing endangered adult in Spokane, according to Chamberlin. Officers in the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office don’t have formal training in missing persons cases involving dementia, nor is there a formal policy, he says, and against the Alzheimer’s Initiatives recommendation, he’s not sure there should be one.

“I don’t think it would be wise to say, ‘Ok, if they have this type of health issue, this is what they’re going to do, this is where you should look,’” Chamberlin says.

The Spokane County Sheriff’s Department receives calls fairly frequently about missing persons with dementia, usually from assisted-living or memory-care facilities, he says. And like most law enforcement agencies in Washington and nationwide, they do have a very good record in nearly all those cases.

That ordinariness may have been what made Sam’s case all the more difficult.

The training gap and possible solutions

Washington is a national leader in search and rescue. It is home to the longest-running annual search and rescue conference in the country. Koester, the author, visits regularly to present the latest research on wandering to search and rescue volunteers and coordinators.

In recent years, however, government belt-tightening has hindered efforts to better equip local law enforcement to handle missing person cases involving dementia, according to interviews by InvestigateWest.

The system appears to have broken down in the face of limited training opportunities for local law enforcement to learn about dementia and, at times, reluctance at the local level to utilize the tools available to law enforcement agencies. Moreover, wandering remains a relatively new concern and hard data on which to design policy are hard to come by, even for top officials. Outside of law enforcement, few systems are in place to help families and communities learn about, prepare for and respond to the growing number of individuals with Alzheimer’s and dementia and prone to wander.

As president of the state’s Search and Rescue Volunteer Advisory Council, Bill Gillespie helps to coordinate the numerous county-level volunteer search and rescue organizations. He also tracks what kind of search and rescue missions that take place around Washington.

The types of searches “are changing,” he says. “We are seeing a significant number of what we call walkaways.”

Even so, Gillespie guesses that as many as a third of all wandering cases that get reported to authorities never cross his desk. By state statute, the local law enforcement chief and local emergency manager have sole responsibility to initiate search and rescue missions. It’s one significant difference between Washington and other states. Local police are sometimes reluctant to call for search and rescue volunteers, and incur the related costs of doing so, when so many cases are wrapped up so quickly, Gillespie and other experts told InvestigateWest. He’d prefer to hear about every one.

“We’ve made it very clear to law enforcement,” he says.

The volunteer council is currently working with the state’s Emergency Management Division to get a more accurate count of missing person cases involving dementia. But it’s slow work corralling rules and regulations across of 39 different counties, Gillespie says.

In 2009, the state gave local law enforcement another potentially helpful tool, but it’s been underused. The Endangered Missing Person Advisory, an analog to the better-known Amber Alert system for missing children, is designed to let the public know when an at-risk individual goes missing, a classification that includes not only Alzheimer’s and dementia but also mental illness. When one of these emergency notifications is activated, all law enforcement agencies in the state are notified, along with ports of entry, media partners and members of the public who have voluntarily subscribed.

Only in the last 12 months have law enforcement officers have been able to issue EMPA advisories through a Washington State Patrol web portal, an option available for Amber Alerts since 2004. No alerts were issued through the portal in 2012, according to Carri Gordon, Washington’s EMPA coordinator; no one had yet received training on how to do so.

“It’s been used not as often as it should be,” Gordon acknowledges.

“The reluctance with law enforcement to use the portal is that it’s statewide,” she says, when most wanderers are found close to home. But she hasn’t seen it create any confusion, and, like Bill Gillespie, she would like to see more police departments take advantage of state resources. “If you believe you have information about the person’s location, you should use” the EMPA system, she says.

It might be that police departments need to know what they don’t know about dementia and wandering. The state patrol offers four trainings per year but, “It’s kind of on them to request refresher training,” Gordon says.

Two bills to create a more comprehensive companion to EMPA called Silver Alert were proposed in the Washington House and Senate in 2013, but neither made it out of committee. Since 2006, more than 20 other states have passed Silver Alert legislation, most recently New Mexico and California, where the program contributed to the safe return of an elderly California man less than 48 hours after it went into effect.

Washington is also one of six states that haven’t even started work on an Alzheimer’s state plan.

“This is really ironic when you consider Washington’s historical willingness to be out in front,” says Bob Le Roy, president and chief executive officer for the Western and Central Washington chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

His group began to lay the groundwork for just such a plan five or six years ago, but a moratorium on new programs under Gov. Christine Gregoire ended its prospects. The 2013-2014 state budget includes $100,000 to establish a committee on aging and disability, but its recommendations are not expected for another 18 months.

Eyes in the sky

Six days after Sam Counts was reported missing, with no leads and the search stretching almost a week, the Spokane County Sheriff’s office put up a helicopter on Thursday, Nov. 29.

Until then the family had just trusted that the sheriff’s office was doing all it could to find Sam. Sue Belote and Deputy Chamberlin had spoken by phone every day, sharing any news or information that might prove helpful to patrol officers or the many friends and family who had volunteered their time to help look. The helicopter, though, came as a surprise to Sue.

“If you could do this, why did it take so long?” Sue says.

At the time, the sheriff’s department couldn’t give her an answer.

For the department, the helicopter is “an absolutely fabulous tool,” says Chamberlin, but it also was a last resort. Spokane County spreads across more than 1,700 square miles, roughly the size of Rhode Island. Much of it is remote, mountainous terrain. The county’s highest point, Mt. Spokane, gains more than 4,300 feet from the public safety building downtown.

“To be quite honest with you it was like finding a needle in a haystack,” Chamberlin says. “They were looking for a white SUV in a community of 700,000 people.”

The first day’s air search in Spokane was fruitless. On Friday, exactly a week after Sam left his driveway in Spokane Valley, and toward the end of their time in the air, searchers flew toward Sam’s old home.

This time Air-1 did locate Sam’s car in Elk, “in the area of 29303 N. Blanchard,” at the edge of Mt. Spokane State Park, according to a KHQ news report. Sam was not inside. After an on-the-ground search by officers and a team of bloodhounds, his body was found, roughly a half-mile away.

Sue Belote and her mother, Donna Counts, at Donna’s home in Spokane Valley.

Credit: Christopher Sherlock/KCTS 9

Looking back, Sam’s family focuses on Elk as the obvious destination that Sam had in mind when he pulled away from the bread store, which had closed early.

“I think he went back in time and he thought he was going home,” says Donna, his wife.

The autopsy report from the medical examiner’s office would lay out in blunt, detailed terms the tragedy that had unfolded: “The jeans are heavily mud-caked,” “The right-coin pocket contains miscellaneous change totaling $2.05,” “a flashlight was in the vicinity of the decedent,” “The decedent had removed his jacket, hat, eyeglasses, T-shirt, and sport-shirt.”

It’s possible that Sam took North Argonne Road north across the Spokane River. He might have turned left on Route 206 and driven past a baseball field. He almost certainly ended up on Route 2 and took the exit for North Elk Chattaroy Road, followings its twists and turns up into the mountains toward Mt. Spokane.

Just over thirty miles from home, the car got stuck in the mud on a logging road switchback. Disoriented, Sam got out of his car. On the night of Saturday, November 24, a fog settled over Elk, Wash., and a 5 mph wind blew from the southwest.

The temperature dropped to 27 degrees.

“We were really keeping our fingers crossed that this was not going to happen,” Chamberlin says. The deputy himself says he had a personal interest in the case, after talking with the family daily and investing so much of his own time into the search.

“I wanted to contact them with different news. I wanted to contact them with good news. And unfortunately it didn’t turn out that way.”

Gillespie, the president of the search and rescue council, doesn’t want to second-guess the decision in Spokane to not send up a helicopter earlier. He says there are all kinds of factors that come into play, and law enforcement personnel make decisions in earnest.

But in general, he encourages a timely response when an adult with dementia is reported missing and at risk.

“Anything that goes on for four or five hours, I better start looking at all the resources I have available to me,” Gillespie says. “That’s when we start pulling out all the stops.”

And helicopters?

“We immediately start looking at that,” he says. “We look at the criticality of the whole situation. If we have an elderly person who has certain medical issues who is gone for over an hour, we need to heighten resource availability immediately.”

The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that there are 323,000 caregivers in Washington who look after people with Alzheimer’s and dementia. Most people with Alzheimer’s disease are not in a memory care facility, and most will wander.

“There’s no stigma attached to a family calling for help,” Gillespie says.

The Counts saga shows how family and caregivers of people with dementia need more information.

“What I miss the most now is he always kissed me goodnight and when he got up in the morning, he always kissed me good morning,” Donna says.

“It’s very, very hard not to have him here,” she says. “People don’t understand.”

“Well I didn’t understand dementia either until it happened to me.”

There is information for caregivers available from Area Agencies on Aging and from local chapters of the Alzheimer’s Association. Radio and GPS-based technologies are available to track the location of people at risk, and they are increasingly sophisticated about when and how they alert caregivers of wandering behavior. With Washington’s rapidly aging population, local law enforcement needs be a bigger part of the solution by educating families and caregivers about these available resources and others, experts say. Law enforcement is on the front line.

“There’s a lot of folks in a lot of areas that don’t know where else to turn,” says Wright, the police trainer. “The police are getting called.”

Sue Belote reflects on what she learned.

“I wish there was more in place to help families going through this,” she says. “You want to see normalcy in them. You hang on to that.”

“He worked his entire life to take care of us ten kids.”

“We didn’t know about the wandering.”

Additional reporting by Daniel Kopec/KCTS 9.

Here’s another one: Two years ago, a 77-year-old Chehalis-area woman wandered away from home on foot and onto the freeway at night. … http://www.lewiscountysirens.com/?p=6563