Robert McClure contributed reporting to this article.

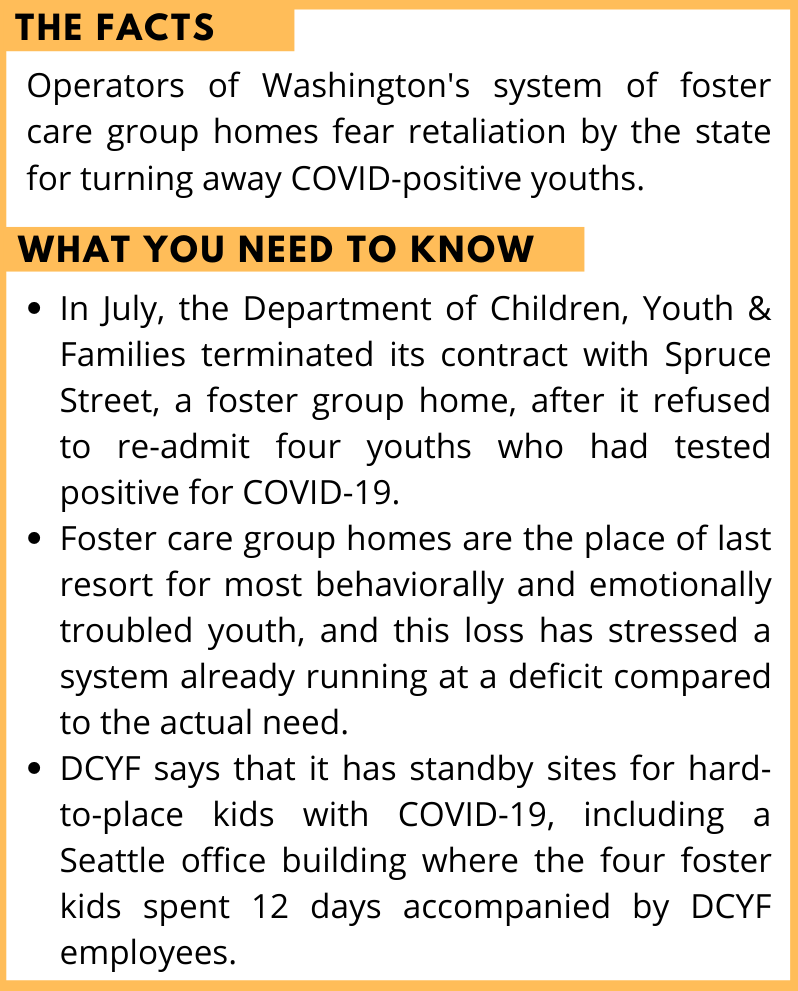

With COVID-19 spreading into Washington’s system of group homes for foster kids, operators of the homes say they are in a precarious position and fear “retaliation” by state child-welfare officials who ended state funding to a home that turned away COVID-positive youths.

Foster care group homes are the place of last resort for the most behaviorally and emotionally troubled youth, those whose problems are so severe that they cannot be housed with regular foster families. A shortage of such slots at in-state group homes has led state officials to send some of the youths to out-of-state homes. Washington’s group homes also house youth without severe problems but who are hard to place for other reasons.

The state Department of Children, Youth & Families in July terminated its contract with the Spruce Street Inn foster group home in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood, which housed 18 of the hardest-to-place youth in the state’s care. Although the state agency has refused to spell out why it made that decision, advocates for foster youth and group homes note that it came after Spruce Street, operated by Pioneer Human Services, refused to re-admit four youths who had gone to the hospital and tested positive for the illness.

The state Department of Children, Youth & Families in July terminated its contract with the Spruce Street Inn foster group home in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood, which housed 18 of the hardest-to-place youth in the state’s care. Although the state agency has refused to spell out why it made that decision, advocates for foster youth and group homes note that it came after Spruce Street, operated by Pioneer Human Services, refused to re-admit four youths who had gone to the hospital and tested positive for the illness.

Brian Carroll, CEO of group-home operator Secret Harbor, said the Spruce Street situation “has got everybody really worried.” Said Carroll, “The contract termination of Pioneer [Spruce Street] … still makes everybody scared if you don’t do exactly as you’ve been told.”

So with a pandemic raging, the state has lost 18 slots that have long been at a deficit compared to the actual need. And it remains unclear what will be done to stop the spread of the disease in these facilities, with the Department of Children, Youth & Families struggling to coordinate a statewide strategy to a virus that affects different group homes in different ways.

“DCYF did not seem to recognize the unique challenges our agencies would face in the event of an outbreak,” wrote Jill May, executive director of the Washington Association for Children & Families, which advocates on behalf of group homes and other child-welfare organizations, in a letter to DCYF in July. “It is imperative the concerns are understood. … Our concerns have been shared repeatedly.”

May also pleaded with state officials not to expect staffers at the homes to work while sick with the virus. In at least one case, with local health officials’ blessing, a home near Spokane allowed COVID-positive staffers to supervise COVID-positive youth.

In an Aug. 6 response to May, Hunter wrote that DCYF never told group homes to keep staffers sick with COVID-19 working at the homes — which May maintains a DCYF official said on a conference call this summer. Hunter also said DCYF is doing its best, and local public health departments would give group homes guidance, according to May, who declined to provide a copy of Hunter’s response, fearing it would anger him.

The Spruce Street incident

Located on a leafy corner a block from King County’s controversial new juvenile jail, Spruce Street Inn was until July where a lot of unfortunate young people ended up, “one of the few select programs in Seattle that provides services to ‘street youth,’ chronic runaways and commercially sexually exploited children,” as the home’s website still said as of Thursday, Aug. 13.

The coronavirus situation at Spruce Street developed fast. On May 13, three foster children at Spruce Street came down with fevers. They went to Seattle Children’s hospital on May 14, where they tested positive for coronavirus. The rest of the foster children at Spruce Street then underwent testing at Seattle Children’s hospital on May 15, with one child getting a positive result but not showing any symptoms. Pioneer spokeswoman Nanette Sorich said that 11 employees of Spruce Street also eventually tested positive for coronavirus.

According to Pioneer, after employees tested positive and went back to their homes, Spruce Street didn’t have enough workers to care for the four children who tested positive and the youth who weren’t. As a result, Spruce Street refused to re-admit those four kids after their coronavirus tests at Seattle Children’s hospital.

“Since some staff tested positive now, the program could not accept the youth coming back from the hospital as Spruce was not appropriately staffed,” Sorich said by email.

Sorich said Pioneer made “every effort” to re-staff Spruce Street using a pool of temporary staffers offered by DCYF. However, only two people from that pool accepted work with Spruce Street.

In addition, Pioneer re-deployed staffers from its other youth programs to Spruce Street and used a staffing agency to fill positions with temporary employees, Sorich said. However, “even with all these efforts, immediately re-staffing the program to full staffing level was not possible,” Sorich said.

Ultimately, the COVID-19 infection that took hold at Spruce Street in Seattle turned the program upside-down and ended the operations of the home by July. That was when DCYF terminated the contract for emergency placement of foster youth at the facility, Sorich said.

When asked whether the Spruce Street program termination was retaliation by DCYF for Spruce Street’s refusal to house coronavirus-positive foster youth, DCYF spokeswoman Debra Johnson said in a phone interview that DCYF “does not act in any type of retaliatory way.”

The Seattle Times first reported the agency’s decision to stop placement of foster youth at Spruce Street in June, following earlier reports by the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform and The Imprint of the COVID turnaways. Was DCYF opposed to Spruce Street’s decision not to re-admit the youths? Johnson, the state agency’s spokeswoman, said only by email that “the termination of a contract is always in accordance with the terms of the agreement.” In a follow-up phone call, she said she didn’t know whether Spruce Street had broken its DCYF contract by refusing to re-admit the four youth. Sorich said in a phone interview that Pioneer has no knowledge of any violation of any part of its contract with DCYF due to its refusal.

Fear spreads among home operators

It’s difficult to know exactly how many group homes have been affected by the virus since it struck Spruce Street in the spring, but it’s clear several more homes have had to deal with outbreaks. If what is happening outside the facilities is any guide, more such outbreaks seem likely, given that there are 88 foster-care group homes in Washington State.

“It’s a very precarious time for us. In order to keep providing for these youth, we have to keep them safe from COVID and keep COVID out of our facilities.” ~ Amy Woodward, program manager of Cedar Creek, a group home north of Spokane

In response to an inquiry by InvestigateWest, Johnson provided a list of four foster-care facilities she said had experienced COVID-19 cases: Spruce Street; Morning Star Boys’ Ranch in Spokane; the James Matthew Commission (JMC) Kid’s Place in Yelm; and Evangeline’s House in Spokane. Johnson did not specify whether the positive tests pertained to staffers, foster children or both.

May, head of the advocacy group for the child-welfare providers, provided a different list of five homes affected with at least one coronavirus infection. They are:

- Spruce Street, Seattle

- Morning Star Boys’ Ranch, Spokane County

- PNW (Pacific Northwest) Helping Hands, Spokane

- Friends of Youth, Western Washington

- Breakthrough, Kennewick

Helping Hands had one staffer test positive, “but there was no infection in the program,” said Blake McFrederick, a vice president at Helping Hands. He refused to give more details, including whether Helping Hands tested its youth for coronavirus. May said the infection occurred in a Helping Hands facility in Spokane; McFrederick didn’t return a second call requesting confirmation.

The CEO of Breakthrough, Nathan Cooper, said that its coronavirus infection — two staffers testing positive — didn’t happen in a foster-care facility, but rather at its one-bed developmental disability facility in Kennewick.

The chief program officer at Friends of Youth, DeAnn Adams, said staffers at two of its facilities in Western Washington — she declined to disclose the locations — tested positive for coronavirus. However, no foster youth had positive results even after days of testing conducted by Public Health – Seattle & King County, she said.

Even where COVID-19 has not yet been detected, operators of other homes are wary after the Spruce Street shutdown.

In her July letter to DCYF Secretary Ross Hunter, May wrote that “many agencies perceived this to be retaliation for an agency’s inability to quarantine youth in place and have expressed concern and worry about their own programs.”

That closure has had a chilling effect on other group homes, with some wondering if they will run afoul of the department and calling the closure retaliation by DCYF. Meanwhile, for a group home, a coronavirus infection could threaten its financial security and scare staffers into staying home or press them into home quarantine — undercutting the group home’s ability to maintain the high staff-to-child ratios that high-needs foster kids need.

“It’s a very precarious time for us,” said Amy Woodward, program manager of Cedar Creek, a group home north of Spokane with six beds for girls and young women in foster care ages 10 to 21. Woodward is nervous about the effects of a potential coronavirus outbreak on staffing, finances and foster kids at Cedar Creek.

“In order to keep providing for these youth, we have to keep them safe from COVID and keep COVID out of our facilities,” she said. To that end, Cedar Creek is allowing its foster girls to leave the home for appointments on an as-needed, case-by-case basis. It also has put its employees on seven-day rotations to minimize their potential exposure to coronavirus in the community. Since March, employees report for work to Cedar Creek and don’t leave the home for the next seven days, sleeping in a converted garage attached to the group home. Staffers also can sleep in a trailer on site, if they prefer. Cedar Creek has both day and night staff for its foster girls.

Woodward is hopeful about getting support from DCYF if coronavirus infections should occur at Cedar Creek. “I don’t believe that they [DCYF] want to lose providers” of behavior-treatment programs like hers, she said.

Kids with COVID kept in office building

DCYF’s Johnson said that, for foster children in a group home that can’t or won’t house them after they test positive for coronavirus or exhibit COVID-19 symptoms, DCYF has sites on standby that can accept them.

Johnson said those sites are Bethel Church in the Tri-Cities, which is a Christian church campus, and an office building in Seattle, a DCYF visitation center on Delridge Way Southwest in West Seattle normally used for foster children to meet with their birth families. The four coronavirus-positive children from Spruce Street recovered in the office building after Spruce Street declined to take them back from the hospital, Johnson said. In follow-up emails, she said the site has a full kitchen and showers. Its six rooms lack windows, she acknowledged, but there are windows in the common areas. Each room is set up for one child and has a bed, TV, DVD player and couch, according to Johnson.

At least four foster youths spent 12 days living in this office building on Delridge Way in West Seattle after they were turned away from a group home when they tested positive for COVID-19, according to the Washington Department of Children, Youth & Families. The agency rents space in the building.

DCYF placed the four foster kids from Spruce Street at the office for a total of 12 days. They were accompanied by DCYF employees who volunteered to work at the site and who received personal protective equipment and training from Public Health – Seattle & King County, Johnson said.

Thus far, “no other facilities have been needed aside from the Delridge site,” Johnson said Tuesday.

The head of a child ministry at Bethel Church in Richland, Windy Hancock, confirmed to InvestigateWest that no foster children, with or without COVID-19, have been housed at the church so far.

Hancock said Bethel Church doesn’t have a written contract with DCYF. “We have agreed to allow them [DCYF] to use our space should they need it,” she said. Saying her region has a lot of foster families, including ones she personally knows who are housing foster children with COVID-19, she doubts the site will be needed.

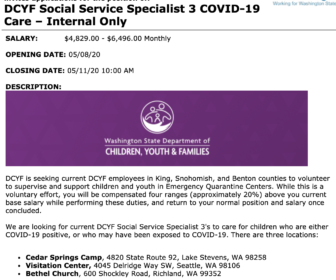

Folks in the Tri-Cities became concerned, though, when they saw the site mentioned in a DCYF job posting that asked agency employees to staff three emergency quarantine centers. The job posting offered a 20 percent pay boost.

When the job ad was spotted by people in the Tri-Cities, it set off alarm bells among confused parents who thought kids not in foster care might be taken there, although that was never the plan.

Screenshot of DCYF job posting for qualified employees to earn 20% bonuses by volunteering to mind foster youth.

The agency’s ad for workers named the Tri-Cities church, the West Seattle office building and the Cedar Springs Camp near Lake Stevens in Snohomish County.

But shortly thereafter, the Snohomish County facility wrote on Facebook that its selection as a site to house infected youth was “a surprise to us and incorrect.”

DCYF eliminated mention of that facility in the job posting, but it remains in numerous versions of the ad still on the web.

Ways to make it work

Comforting 23 troubled foster children, the animals at Morning Star Boys’ Ranch in Spokane County include horses, goats, chickens and lambs. They help the boys soothe the extreme behaviors and emotions that landed the children at the ranch. On the last weekend of June, however, this foster-care group home added a new and disturbing creature: Coronavirus.

As at Spruce Street, the virus posed a test that has challenged foster-care facilities across Washington since the spring: how to treat foster children who test positive for coronavirus or show COVID-19 symptoms in small group settings without sickening employees or even more children.

At Morning Star, the solution was simple and elegant: relocate the coronavirus-positive boys to a yet-unused but fully operational wing of the home, complete with air conditioning and new bedding. Guided by the local public health department, Morning Star succeeded in getting the children to isolate and recover in the wing. The Department of Children, Youth & Families, the state foster-care agency, didn’t make any changes to Morning Star’s state contract during the outbreak, Morning Star said.

Talking about the coronavirus-induced financial strain and staffing issues for group homes, Carroll, of Secret Harbor in Snohomish County, noted, “The pressures are enormous.”

“All of these decisions about whether your program stays open … the business impact of these things is enormous,” Carroll said.

Secret Harbor, which runs a six-bed group home for 10- to 14-year-old foster boys in Sedro-Woolley and a six-bed group home for 14- to 21-year-old foster boys and young men in Burlington, has shelled out $4,000 for 1,000 N95 masks as part of its coronavirus preparedness, Carroll said. He said he doesn’t plan to ask DCYF to compensate Secret Harbor for even part of the outlay.

“We wouldn’t ask for that,” Carroll said. “It’s just part of the price of doing business right now.”

Inside Secret Harbor’s Lillian Johnson Home in Burlington, Wash. Secret Harbor has spent $4,000 for 1,000 N95 masks as part of its coronavirus preparedness at its group homes, said CEO Brian Carroll. “The pressures are enormous,” he said of the coronavirus-induced financial strain and staffing issues for group homes.

Secret Harbor also has been adding hazard-duty pay to its workers’ salaries to attract them to keep coming to work amid the coronavirus pandemic. Any worker who has direct contact with the boys has gotten a $3 per hour pay increase, which has translated into an additional $11,000 per month in staff salaries, Carroll said.

“It all boils down to workforce,” he explained. “You can have people well enough to come to work, but they have to be willing to come to work.”

Like Cedar Creek, “we’re trying to protect the home environment as much as we can,” Carroll said. Before guests enter the group homes — whether DCYF caseworkers or Carroll himself — a staffer checks their temperatures, asks about COVID-19 symptoms and discusses recent community activities. If a foster child leaves the home, he is accompanied by a staffer, who can keep tabs on his activities.

Any group home that finds itself with a foster child who has COVID-19 symptoms or “a known exposure” to coronavirus should “immediately contact” its local health department for guidance, according to a memo issued by the Washington State Department of Health.

DCYF is “supporting licensed-by-DCYF group care foster care providers to comply with DOH guidance,” DCYF spokeswoman Johnson said by email.

In Washington, local health departments have primary responsibility for handling coronavirus cases in their jurisdictions, since the Washington Administrative Code gives them primary responsibility for “notifiable conditions,” according to Department of Health spokeswoman Amy Reynolds. Local health departments typically cover a county.

Morning Star notified the Spokane Regional Health District on June 29, the day that Morning Star learned that it had a coronavirus problem, said Kim Morin, a spokeswoman for the group home.

After working that weekend with the foster boys, an employee had developed a migraine on June 28 and a fever the next day, then alerted Morning Star. Rapid coronavirus testing yielded the news that every boy whom the employee had worked with was positive for the virus.

In all, nine boys at the home tested positive, seven of them asymptomatic and two of them with low-grade fevers, nausea, vomiting and severe headaches. Among employees, 11 had positive virus test results, and all of them had symptoms, though mild, according to Morin.

All of the positive tests and symptoms belonged to foster children and employees at Morning Star’s Murphy House Therapeutic Residential program, which has 23 beds for boys ages 6 through 13 1/2. Morning Star’s other services, such as its foster-care licensing, weren’t touched by the outbreak, Morin said.

Guided by the Spokane health department, Morning Star moved all of the coronavirus-positive boys into an empty, newly built wing that has an additional eight beds. In dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, “our greatest asset was having that separate wing,” Morin said.

A calendar with August appointments hangs on the wall at Secret Harbor’s Lillian Johnson Home in Burlington, Wash., with the current date of Aug. 12, 2020 reflecting the House Manager Frank Hasenbalg’s birthday.

Morin also said “having a really great relationship with whoever your regional health district is” will be a plus for any other group home experiencing a COVID-19 outbreak. “Our health district here … has been a dream” to work with, she said.

Mark Springer, an epidemiologist with the Spokane Regional Health District who was one of the consultants on the Morning Star situation, said his health department gave its approval to “cohorting,” in which two Morning Star staffers who had tested positive for coronavirus but recovered from their symptoms worked in the wing with the foster boys.

“That was a perfect opportunity for cohorting,” Springer said, and it helped Morning Star at a moment when it was short-staffed, he added.

Each foster-care group home is supposed to review and update its “infection control preparedness plan” in order to ready itself for a COVID-19 outbreak, according to the memo from the Washington State Department of Health.

Group homes already had developed disease control plans prior to the coronavirus epidemic as part of their accreditation process, according to DCYF. In March, acting on Department of Health guidance, DCYF requested that all foster-care group homes come up with COVID-19 prevention and intervention plans specific to their programs and facilities, including quarantine and isolation plans, Johnson said.

The Department of Health memo calls for group homes to “work with DCYF and local public health to fill staffing gaps.” It notes that DCYF has a “temporary youth worker staffing pool” and that “most local public health agencies maintain volunteer registries.”

In the latest iteration of its memo, dated July 9, the Department of Health advises foster-care group homes to tell symptomatic children and their coronavirus-exposed roommates to stay in their rooms. When that isn’t possible, the home should group symptomatic children together in one part of the facility “or use the facility as a group quarantine space.”

The memo also outlines contingencies for when a foster child can’t be isolated in the home, instructing it to “work with local public health to plan for an alternate strategy” such as a stand-alone cottage, a hotel room staffed by a nurse or, in the case of severe symptoms, a hospital room.

Also pointed out in the memo is the fact that “because residents [foster children] often have a significant history of trauma, it will be important to work with local public health to develop the best trauma-informed strategies for quarantine and isolation, which may require alternate strategies to retaining youth in a room for isolation and quarantine.”

Program manager Woodward at Cedar Creek, which serves disturbed foster youth, is keenly aware of the difficulty of trying to get emotionally traumatized foster children to comply with strict coronavirus measures. The foster girls who land in Cedar Creek’s special behavioral rehabilitation beds are ones whose behavior has made it impossible for DCYF to place them in a regular foster home, Woodward said. The girls’ problems are so extreme that, should Cedar Creek not work for them, the next placement for them could be a bed in CLIP, or Children’s Long-Term Inpatient Program, an intensive inpatient psychiatric treatment program.

“Trying to keep those youth in quarantine or to keep their masks on or not spit on or assault staff is a task in and of itself,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the nature of the jobs in an internal Department of Children, Youth and Families job posting.