Labeled “Firmageddon,” by researchers, the drought-driven “mortality event” is the largest ever recorded in the region

By Nathan Gilles / Columbia Insight

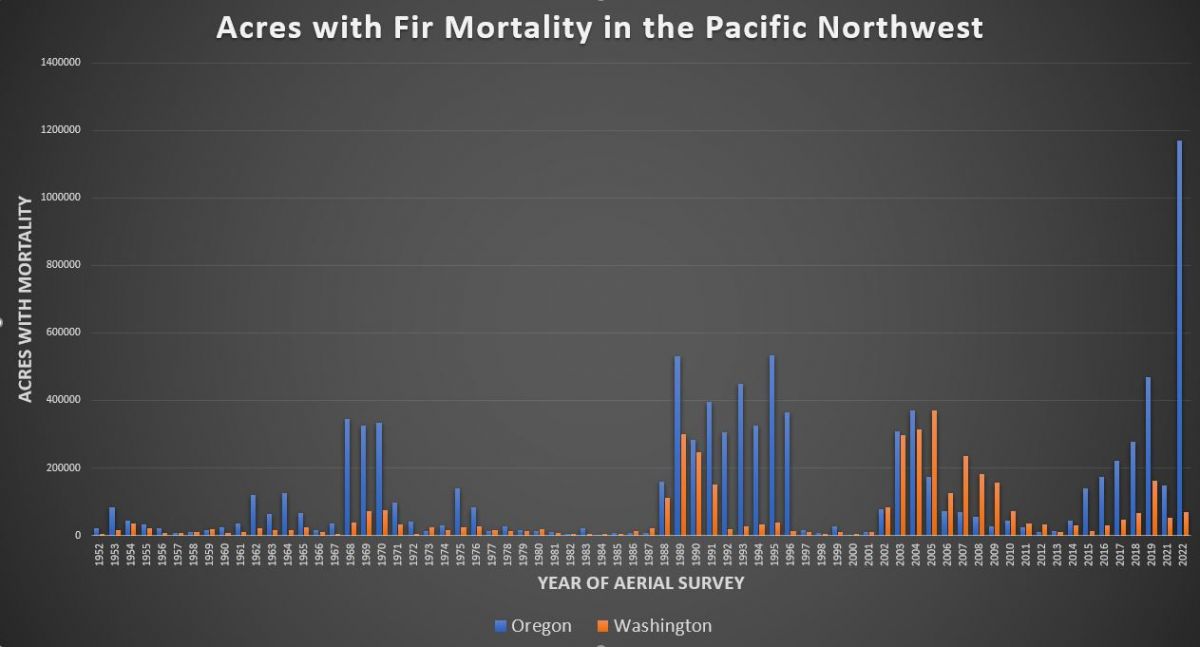

Fir trees in Oregon and Washington died in record-breaking numbers in 2022, according to as-yet unpublished research conducted by the U.S. Forest Service.

Called “Firmageddon” by researchers, the “significant and disturbing” mortality event is the largest die-off ever recorded for fir trees in the two states.

In total, the Forest Service observed fir die-offs occurring on more than 1.23 million acres (over 1,900 square miles) in Oregon and Washington.

Oregon, however, was the hardest hit. The Forest Service observed dead firs on roughly 1.1 million acres (over 1,700 square miles) of forest in Oregon alone. This year’s numbers for the state are nearly double the acres recorded during previous die-offs.

Heavily affected areas include the Fremont, Winema, Ochoco and Malheur National Forests.

The most southerly of the forests, the Fremont National Forest, was the hardest hit, according to survey data.

“We’re calling it ‘Firmageddon,’” Daniel DePinte, who led the survey for the USFS Pacific Northwest Region Aerial Survey, told a gathering of colleagues in October. “It is unprecedented, the number of acres we have seen impacted. It’s definitely significant and it’s disturbing.”

Fatal factors

In an interview with Columbia Insight, DePinte says although his team’s results are preliminary and further analysis is needed, the 2022 Firmageddon appears to be due to a combination of drought coupled with insects and fungal diseases working together to weaken and kill trees.

Extreme heat, including last year’s record-breaking “heat dome,” is also being investigated as a possible cause.

“When a drought event comes around it basically weakens the entire forest to a point where the insects and the diseases start to work in tandem and this pushes a tree over the edge and it succumbs to mortality,” says DePinte.

What’s noteworthy about Firmageddon isn’t just the total area impacted. It’s the number of dead trees within that space.

In some areas as much as 50% or more of fir trees are estimated to have died.

These “severe” die-off’s occurred in central Oregon in forests running from the Oregon/California border northward, according to survey data.

Survey method

Surveys of forests were conducted using a combination of fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, drones and satellite imagery.

The surveys were primarily conducted, as they have been for decades, using an airplane flying 1,000 feet over forested land.

DePinte and his team surveyed forests on federal, state and private lands, adding up to a total of roughly 69 million acres (over 100,000 square miles) in Oregon and Washington.

Small sections of California and Idaho, where national forests spill over the state borders, were also surveyed.

The Oregon Department of Forestry and Washington Department of Natural Resources also participated in the effort.

Although fir die-offs have been recorded as far back as 1952, when surveys began, this year’s Firmageddon dwarfs all previous records.

The USFS did not conduct aerial surveys in 2020 due to social-distancing rules around Covid-19.

Which fir species impacted?

Firmageddon, as the researchers define it, appears to be limited to so-called “true fir” trees; trees in the genus Abies.

The Pacific Northwest’s leading timber crop, Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), is not in the genus Abies and is not considered to be a true fir.

Die-offs were recorded for grand fir, white fir, red fir, noble fir and the hybrid Shasta red fir.

The largest mortality was observed at lower elevations where grand fir and white fir are plentiful.

White fir was the hardest hit species, according to survey data.

Doug fir die-off

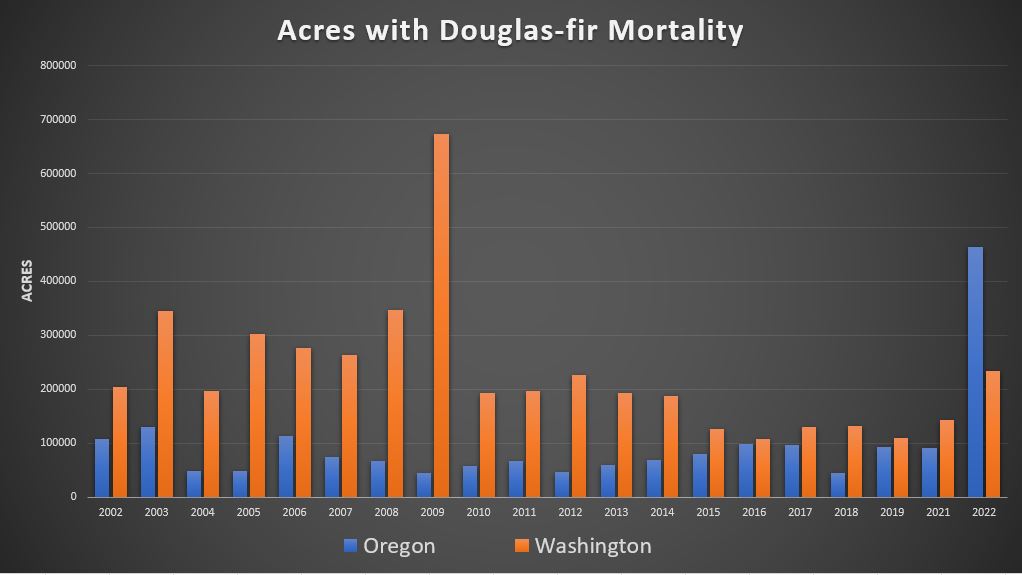

Although true firs are experiencing their worst die-off on record, Douglas fir is having a die-off of its own, though on a comparatively smaller scale.

The USFS survey estimates that 450,000 acres (over 700 square miles) of Douglas fir have experienced some level of mortality in Oregon with the majority of this occurring in southwestern Oregon.

Washington is also seeing a die-off of Douglas fir with roughly 230,000 acres (nearly 360 square miles) impacted.

The level of Douglas fir die-off within the areas affected isn’t considered “severe.” The USFS defines “severe” as 50% or more of the trees within an area having died.

However, the extent of the die-off in terms of total area is concerning, according to DePinte.

“It [the Douglas fir die-off] is on the lighter side,” says DePinte. “The problem is the extent. When you’re up in a plane flying over and you see that it goes on for the entire mountain side, then it’s like, ‘Whoa! That’s a huge amount of dead trees.’”

What’s really unusual, according to DePinte, is the insects that are believed to be causing the Douglas fir die-off are considered to be “secondary agendas.”

The insects have the ability to kill trees that are already weakened by drought or extreme heat events, but generally can’t kill the trees on their own.

“They can kill trees, but they’re not ‘tree killers,’” says DePinte.

The USFS will continue monitoring the Douglas fir die-off and will meet with researchers at Oregon State University in the coming weeks to study the issue further.

Although more analysis is required, drought appears to be weakening Douglas fir trees, making them susceptible to insect and possibly also fungal attack.

This also appears to be the mechanism affecting true firs.

Wide spread: The dead trees in this piece of the Fremont-Winema National Forests are all true firs, a mixture of white, red and Shasta fir. (Daniel DePinte/USFS)

Insects, fungi compound problems

“I think it’s sort of a ‘death by a thousand cuts’ kind of thing,” says Robbie Flowers, a USFS entomologist, about the likely cause of the fir die-off.

Firmageddon has not one cause but multiple compounding causes, according to Flowers.

Flowers, who conducted on-the-ground surveys of tree mortality to, in effect, “ground truth” the aerial survey data, says a clear relationship between drought and fir die-offs has been observed historically—droughts tend to lead to fir die-offs.

When drought occurs, says Flowers, fir trees become susceptible to pests.

The pests implicated in Firmageddon are the fir engraver beetle (Scolytus ventralis), a type of bark beetle; and multiple fungal root diseases.

Various parasitic fungi can make fir roots less able to absorb water. This makes the trees more susceptible to drought conditions.

Firs with root disease are also more susceptible to insect attacks, especially from the fir engraver beetle, which gets its name because it burrows and carves up the water-rich cambium layer of a tree just under the bark.

The fir tree’s only defense against this attack in its cambium layer is to flush the insects out with pitch. But if drought and root diseases make water less available, the trees can’t mount a defense.

As a consequence, says Flowers, a large enough fir engraver infestation can effectively “girdle” an already water-stressed fir tree.

“The trees have a limited amount of resources they can put into defense and their defenses go down then they get into these stressful situations,” says Flowers.

Drought’s fingerprint

That drought is very likely weakening fir trees and making them susceptible to infections isn’t surprising.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, Oregon and Washington have been in some form of drought since the early 2000s.

The recent dieback of western red cedars has also been linked to drought by area researchers. (A dieback occurs when a tree or other plant begins to die from the tip of its leaves or roots inward. Unlike die-offs, which count dead trees, diebacks count dead, dying and sick trees.)

While observed on redcedars experiencing dieback, biotic factors like insects and fungi were estimated by researchers to be secondary to drought as the leading cause of tree illness and death.

The spread of fir die-off and the spread of drought in Oregon match closely.

In fact, DePinte notes, those areas of Oregon that have been especially hard hit with “extreme” and “exceptional drought” (as defined by the Drought Monitor) are the same areas where his team observed the largest die-offs of firs.

Increased risk of wildfire

Unsurprisingly, having more than half the fir trees dead in some of these forests poses a major fire risk.

A dangerous fire period can occur within the first two years following a major die-off, says DePinte.

During these critical first two years, dead trees continue to hold onto their dried-out needles in the canopy of the forest.

This makes severe crown fires far more likely should a fire start.

When this happens fire can jump from treetop to treetop, leading to large scale destruction.

“It [wildfire] can just go from tree to tree, not even touching the ground hardly, and just burn the entire canopy,” says DePinte. “That is the worst fire there is. It’s the most dangerous and hardest to control.”

FEATURED IMAGE: Green going: The Pacific Northwest Region Aerial Survey is cataloging tree decline. (Daniel DePinte/USFS)

This story first appeared at Columbia Insight. Nathan Gilles is a freelance science writer based in Vancouver, Washington.