In Oregon and Louisiana, hundreds remain behind bars two years after U.S. Supreme Court outlawed split-jury verdicts

By Kaylee Tornay / InvestigateWest

Published in partnership with The Washington Post

SALEM, Ore. — Among the 24,000 people incarcerated in Oregon, Eric Russell, Brandon Gillespie and Jacob Watkins are three members of an odd fraternity.

There’s nothing immediately obvious to group the men together. Russell, originally from Portland, is serving the 10th year of a nearly 17-year sentence related to a string of armed robberies. Gillespie, who’s from Jackson County on the California border, has 10 years left on a 27-year sentence for armed robbery. And Watkins, from the middle of the state, is in the final year of a 12-year sentence for sex crimes with a minor.

The common thread is that each was convicted by a divided jury — a situation that, throughout the history of the United States, has only ever been allowed in Oregon and Louisiana. In federal court or in any other state court, a jury that can’t come to a unanimous decision would produce a mistrial.

The U.S. Supreme Court declared split-jury verdicts unconstitutional in 2020, in a ruling known as Ramos v. Louisiana.

Oregon had been allowing split-jury verdicts since 1934, after a Jewish man accused of murder was convicted of a lesser charge because of a single juror holdout. Louisiana enshrined non-unanimous juries in its constitution in 1898, during a convention where the stated purpose was “to establish the supremacy of the white race in the state.”

The Supreme Court ruling left it up to Oregon and Louisiana to figure out what to do with the hundreds of people already in prison for such convictions. On Oct. 21, Louisiana’s Supreme Court ruled against vacating those convictions, leaving the door open for the state legislature to take action. Oregon’s Supreme Court is similarly poised to rule on the issue, in an appeal of Watkins’s conviction that could impact an estimated 250 to 300 other inmates in the state.

If the state Supreme Court sides with Watkins, it would provide the path forward that prisoners and their advocates have fought for — an opportunity to seek new outcomes through the appeals process. Crime victims and their supporters, however, say such defendants should not always get another chance.

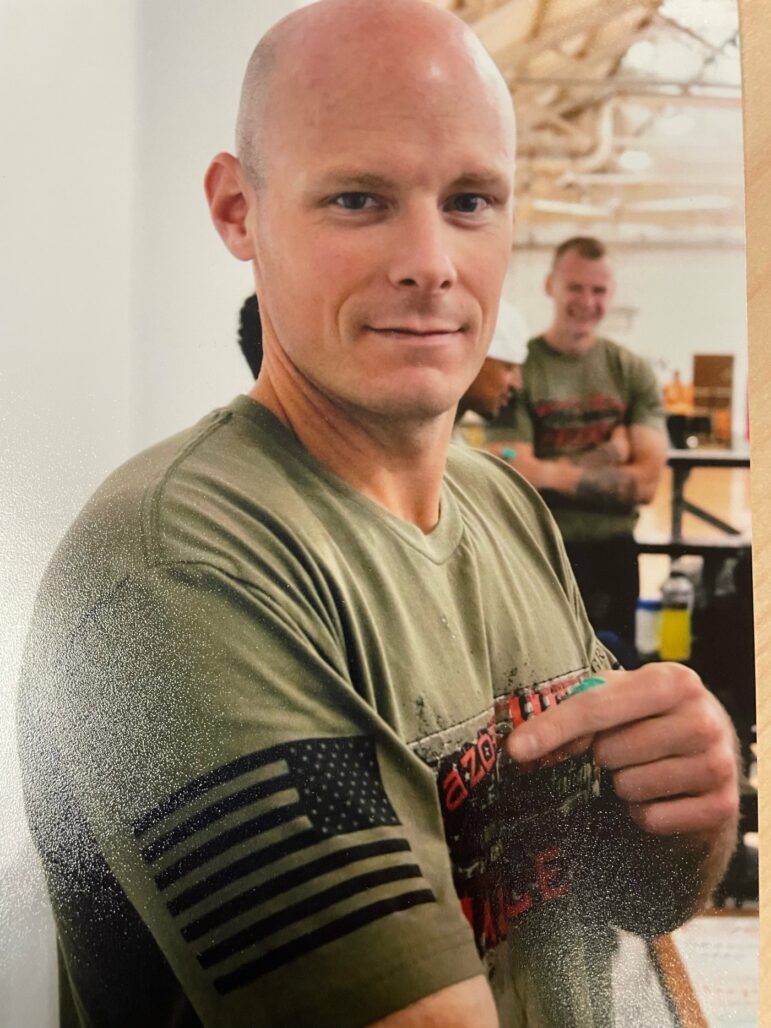

Eric Russell, 38, is incarcerated at the Oregon State Penitentiary. Out of the seven charges he was convicted of in court, five were on non-unanimous verdicts. “They have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt,” he said. “If only 10 or 11 jurors find me guilty, there still is reasonable doubt.” (Photo courtesy of Aliza Kaplan)

The court could kick the issue back to the state legislature, where a bill that would have allowed prisoners to appeal their non-unanimous convictions died in committee this year. Advocates have also asked Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum (D) to address the situation, but she has said she does not have that option under the law.

If no branch of the government takes action, hundreds of people will remain behind bars for crimes that at least one juror did not believe they committed.

“I have a constitutional right and when that constitutional right was violated, I feel I was treated unfairly,” said Russell, 38, who is incarcerated at the Oregon State Penitentiary and was convicted of seven charges, five on non-unanimous verdicts.

“They have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt,” he said. “If only 10 or 11 jurors find me guilty, there still is reasonable doubt that this wasn’t the crime that was committed.”

Racist roots

When defense attorney Aliza Kaplan moved to Portland from Brooklyn in 2011, she was stunned to learn that Oregon allowed non-unanimous jury convictions.

“I was like, ‘This is the most ridiculous thing I ever heard,’” said Kaplan, who directs the Criminal Justice Reform Clinic at the Lewis & Clark Law School. “Because how could there not be reasonable doubt? So I kind of made a mental note to myself, ‘Oh, that’s something I want to learn more about.’”

By digging through old newspaper clips and other research, she learned Oregon voters passed a constitutional amendment allowing split convictions after the 1933 trial of Jake Silverman, a Jewish man accused of a murder near Scappoose, Ore.

Silverman was convicted of manslaughter as a compromise, after a single juror disagreed with the initial charge of second-degree murder. Many reactions to the situation were racist and ethnocentric. An editorial in the Morning Oregonian newspaper faulted “the increased urbanization of American life” and immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, people it said were “untrained in the jury system.”

The next year, 58 percent of Oregon voters approved a constitutional amendment allowing convictions on 10-2 jury verdicts.

Louisiana was and would remain the only other state to allow people to be convicted on split verdicts. It first embraced the practice in 1880 as a repudiation of constitutional amendments that guaranteed Black people the right to vote and, by extension, serve on a jury. Initially, Louisiana allowed convictions with up to three no votes. In 1973, the requirement shifted to at least 10 jurors for a conviction. Louisiana stopped the practice in 2018.

Kaplan’s research has shown that split verdicts disproportionately affect racial minorities in Oregon, where the practice continued until 2020. Black people make up 18 percent of applicants for a new appeal since the Ramos decision, despite making up only 8.7 percent of Oregon’s prison population. Latino people are also overrepresented.

Both the history and the data have fueled Kaplan’s drive to end the practice and address the harm she says it has done.

“As a Jewish person with immigrant grandparents, to read the history, it’s personal,” she said. “The reason behind passing this law, it’s reactionary to what was going on in society, the immigration of Catholics and Jews from Northern and Eastern Europe. Those are my family.”

No action from executive branch

Much of the criticism about Oregon’s failure to address split-verdict convictions since they were ruled unconstitutional has been directed at the state attorney general.

Rosenblum filed a brief with the U.S. Supreme Court in the Ramos case that defended the use of non-unanimous convictions, even as Gov. Kate Brown (D) and former Gov. John Kitzhaber (D) joined Kaplan in a brief taking the opposite position. In 2021, her office asked the Supreme Court not to retroactively apply the new unanimity standard.

Rosenblum, through a spokesperson, declined to respond directly to criticism about her stance on the issue. In a 2021 guest opinion published by the Oregonian/Oregonlive, she reiterated her view that Oregon law provides no way for her office to grant new reviews of non-unanimous convictions in cases when all appeals have already been exhausted.

“When I was sworn into this job … I took an oath to uphold and enforce the law as it stands — not as I would prefer it to be,” Rosenblum wrote. “No Oregonian should want to vest the state attorney general with the power to disregard state law — or to substitute her judgment for that of the Legislature or the courts.”

Rosenblum pointed to actions she has taken to resolve the issue, such as telling her solicitor general to expedite appeals so the issue could reach the Oregon Supreme Court sooner.

But Kaplan and other advocates contend Rosenblum has made it harder for cases to move forward by opposing many of the split-verdict appeals.

“Our attorney general could have not fought these cases to start with,” Kaplan said. “From the beginning, she has said, ‘I’m all for it personally, but it’s my job to follow the law.’ But that’s what people say all the time, even when it’s an unjust law.”

Brown, the governor, has not responded to appeals for clemency for several people convicted by split juries, including Russell and Gillespie. Her office didn’t respond to questions about the status of those applications.

Prosecutors and victims

In Louisiana, where about 1,500 people convicted by non-unanimous juries are still in prison, one local prosecutor was taking action even while the state Supreme Court deliberated.

District Attorney Jason Williams has reviewed about 70 cases, according to Hardell Ward, managing attorney for the Jim Crow Juries project run by the Promise of Justice Initiative, which helped spur the successful effort to get Louisiana to abandon the use of non-unanimous jury convictions in 2018.

Some people were offered plea deals that resulted in lessened sentences. One person was exonerated, Ward said: “That’s another one of the reasons why these cases deserve another look.”

An Oregon law that took effect in January would also allow local prosecutors to similarly review past non-unanimous convictions in their jurisdictions. So far, it doesn’t appear that any prosecutors have opted to pursue that option, Kaplan said.

Multiple voicemails left with the executive director of the Oregon District Attorneys Association went unreturned, and three district attorneys declined an interview or did not respond.

Some crime victims and their advocates have opposed new appeals for people convicted in split verdicts, testifying against legislation that would have allowed them. Lynae Wever said the man who sexually abused her and her sister was convicted on an 11-1 verdict. She begged lawmakers not to allow a way for him to appeal his case.

“I speak on behalf of all the victims going through what I am forced to go through when I say that sexual abuse in any degree should not be given any opportunity for a retrial,” Wever said.

Rosemary Brewer, executive director of the Oregon Crime Victims Law Center, objected to the bill on the grounds it made no provision for additional services for victims.

“This is going to raise a lot of trauma for victims,” she said in a recent interview.

Legislators tried to fine-tune the bill, including narrowing who would be eligible to petition for their cases to be vacated. The bill also included a budget request for $6 million for victims services, a cost that at least one lawmaker believed contributed to its demise.

The bill never made it out of the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Ways and Means.

“It was too tough of an issue to try and get through [in] a relatively short time period,” Brewer said.

The fight was bitter enough that Kaplan said she does not think she would want to lead any future efforts to get a similar bill passed.

“In the last round it got really personal,” she said. “The usual pitting victims against defendants, and I didn’t expect it. That’s just politics, I guess.”

Before the court

Portland attorney Ryan O’Connor argued Jacob Watkins’ case before Oregon’s seven Supreme Court justices in May.

His arguments centered on the idea that split-jury convictions were never valid under the U.S. Constitution. The issue is “so significant and fundamental to the fairness of an outcome of a criminal trial,” he said, that Oregon law inherently allows for new appeals in that case.

“The U.S. Supreme Court said a non-unanimous verdict is not a verdict,” O’Connor said. “It should have been a mistrial.”

The antisemitic and anti-immigrant roots of the practice, he said, also “weighs really heavily in favor of invalidating” split-verdict convictions.

The attorney general’s office declined to comment ahead of the court’s ruling. In its brief and oral arguments, though, the department contended that the impacts of non-unanimous verdicts do not meet Oregon’s legal criteria for reopening those cases.

Both parties said they expect the supreme court to issue its ruling this fall.

Brewer, the crime victims advocate, said she anticipates a number of plea deals if the Oregon Supreme Court rules in Watkins’s favor and the cases of people convicted by split juries go back under review.

“My worry is a deluge of cases coming back and decisions are going to have to be made rapidly,” she said. “We have to make sure there is consideration for victims and their myriad of views.”

For Gillespie and Russell, the stakes are equally personal. Both describe growth they’ve experienced while incarcerated and ambitions they now have to work and provide for their families.

“There were months I wanted to give up and not do anything at all,” Gillespie said. “It’s been a long road.”

Russell said he doesn’t resent the time he served for the wrongs he did. To be cleared of his unconstitutional verdict would impact not only him, he said, but also his family, including his three children.

“I have a better outlook on life. I have more of a determination and focus in life,” Russell said. Being able to appeal his split-verdict conviction, he added, “would allow for the opportunity to give back to my community and have a second chance to be a father to my kids.”

FEATURED IMAGE: Aliza Kaplan, a criminal defense attorney, has been advocating on behalf of prisoners languishing in Oregon prisons for years after their convictions were ruled unconstitutional. “As a criminal lawyer, I was like, ‘This is the most ridiculous thing I ever heard,’” Kaplan said. (Leah Nash/InvestigateWest)

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Reporter Kaylee Tornay can be reached at kaylee@invw.org.