As electricity markets evolve, a noted economist says several proposed renewable-energy projects could cost more than they’ll ever make

By Steven Hawley / Columbia Insight

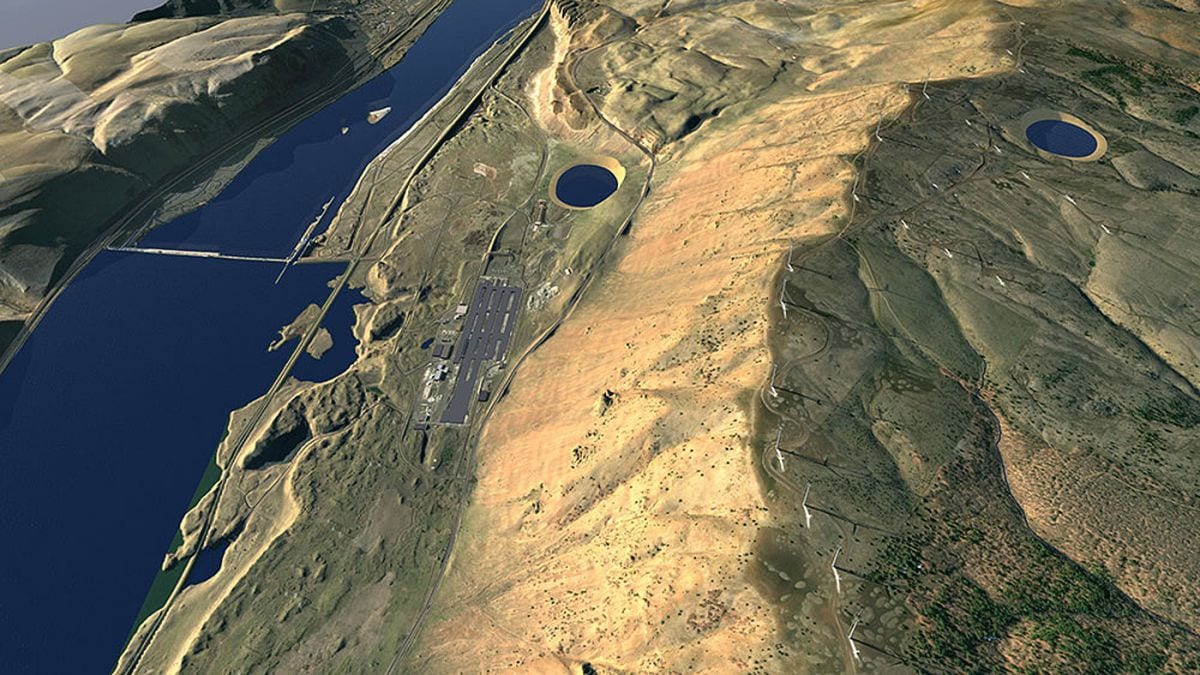

Two proposed hydropower projects in southern Oregon, and a third just across the Columbia River near Goldendale, Wash., have so far generated no electricity, but plenty of controversy.

Environmental concerns have put the brakes on pumped hydropower storage in the region, with opponents citing the effect of high-voltage power lines on migrating birds, and the havoc construction of dams and reservoirs would wreak on sites of cultural significance to Klamath and Yakama Nations.

Boston-based Rye Development, the company managing two of the projects, has promised to work with stakeholders to address their concerns. A third project, on the Owyhee, is a project of rPlus Hydro.

But a more complicated problem awaits each of these energy projects should any of them be completed: will they generate enough revenue to keep their doors open?

According to one veteran energy consultant, it’s unlikely that any pumped-storage project in the region will turn a profit, and it will be a challenge for the proposed operations to simply to meet debt payments and operating costs.

Earnings report

Tony Jones lives outside of Boise. He’s worked for Idaho governors Phil Batt and Dirk Kempthorne, each of who were impressed with Jones’ accurate prediction of Idaho’s energy picture on the heels of deregulation in the late 1990s.

A push on the part of staunchly conservative legislators in the state to deregulate energy markets was unsuccessful, and despite forecasts that Idaho would be left behind in a market-driven low-price revolution, Jones accurately predicted nothing of the sort would happen. He was right.

Since then, Jones has founded Rocky Mountain Econometrics, which specializes in environmental issues with particular emphasis on energy and the impact of hydroelectric dams on salmon and the environment. In addition to those Idaho governors, past clients include Idaho Rivers United and the National Wildlife Foundation.

In 2019, he was commissioned by the conservation NGO American Rivers to assess the economic viability of the proposed Goldendale project. His conclusion: the $2.5 billion price tag would cost more than the project would ever likely earn.

One of the few ways it could ever make money, wrote Jones, would be if the owners stiffed their investors by declaring bankruptcy, and different owners were able to acquire the infrastructure for pennies on the dollar.

“They said I’m wrong, that I don’t understand how the plant will operate,” says Jones. “As an economist, I’ve always been open-minded. I say, ‘Okay, make me smarter. Tell me where the money comes from, because I’m just not seeing it.’ They got kind of pissed at me when that report came out, but they didn’t prove me wrong.”

Jones was hired to analyze another proposed pumped-storage project in Idaho, on a fork of the Boise River, and drew similar conclusions to the Goldendale site.

At the request of Columbia Insight, he took a brief look at the two Oregon projects: the $850 million, 400-megawatt Swan Lake project near Klamath Falls; and a $1.5 billion, 600-megawatt proposal that would be built near the Owyhee River.

“The Klamath project doesn’t look as troubled [as Goldendale],” says Jones. “But that doesn’t mean it’s not troubled.”

Jones was unimpressed with the Owyhee project, as well.

“That proposal comes with some numbers I was able to access, and it looks to me like it’s projected efficiency is only going to hit about 36 percent,” says Jones. “That means that most of the time, it will just be sitting out there, the reservoirs evaporating in the desert.”

Tricky timing

The challenge for pumped-storage hydro lies in its claim to be a reliable, cost-effective backup “battery” for renewable, but intermittent sources of energy like solar and wind power.

When the wind stops blowing or the sun doesn’t shine, some other source of generation, driven by batteries, fossil fuel or conventional hydropower, is needed.

The question for pumped storage is how it stacks up against these other options.

Prohibitive up-front capital costs are a significant drawback, says Jones, but not the biggest problem.

Closed-loop systems like the ones proposed in Oregon by Rye Development will rely on pumping water uphill from a lower reservoir to an upper reservoir via a subterranean pipe when the price of electricity is low, and moving the same water back down the pipe to spin a turbine when the price of energy is high.

According to Jones’s analysis, the timing, duration and distances in daily price swings in western energy markets don’t translate to profitability for pumped storage. Jones predicts that the Goldendale pumped-storage project will require a $102 per-megawatt-hour price to turn a profit.

In April 2022, during an unusual cold snap, electricity prices in the region averaged around $45.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council, which has provided the Pacific Northwest with detailed energy supply-and-demand forecasts every five years since 1980, says in its latest draft plan that prices for power in 2021 ranged from $18 to $30 per megawatt hour. By 2026, the projected range is $12 to $17 per megawatt hour; by 2041 around $10 per megawatt hour; and by 2041 “significant levels of low or no-cost power will be available most daylight hours throughout the year.”

Power surge

Dramatic changes in both supply and demand for energy are fundamentally reshaping western energy markets. Primarily because of the 14,000 megawatts of solar power installed in California over the past 20 years—an astonishing accomplishment, exceeding the capacity of the federal hydropower system on the Columbia River—the timing of peak demand, which used to be midday, has been flattened and then some.

On many days, the midday price for power goes negative—producers are actually paying consumers to take it off the grid.

In addition, peak demand has been pushed to late afternoon and early evening, when solar panel production wanes as the sun goes down, but energy demand rises.

Energy wonks have taken to calling this re-shaped daily demand a “duck curve,” as the hours of energy use plotted over a day now resembles the shape of a duck’s back and neck.

“For these projects to be profitable they [pumped storage producers] will need eight to 10 hours of the high prices that go along with high demand,” says Jones. “But instead, they’re getting one to two hours.”

Even if pumped storage wants to compete for those one to two hours of peak price, says Jones, other sources have a natural advantage.

Tesla, for example, is back-ordered for a year on its utility-scale Megapack battery array. Each unit can store and then deliver on demand up to three megawatt hours of electricity. For $850 million, Tesla will sell you a hundred of these at a time—and utilities are lining up to get them.

The California utility Pacific Gas and Electric, for example, announced on April 18 that its 233 Megapack array with 750 megawatts of backup power was fully operational.

Crunch the numbers: for under $2 billion, PG&E got 350 megawatts more of what Swan Lake has promised, but with a smaller footprint, and with other, more nuanced advantages. For a variety of technical reasons, batteries will be able to meet shorter, steeper spikes of demand better than pumped storage.

“By the time a pumped storage system is ready to respond, the battery guys will have taken the price spike off the table,” says Jones.

Hold up a sec

Adam Schultz is the Oregon Department of Energy’s Electricity & Markets Policy Group lead.

He points out that the market forces at play in California and the West may not affect Oregon’s pumped-storage projects as directly as Tony Jones prognosticates.

“In Oregon, we still have vertically integrated utilities that are looking at an energy portfolio to meet their needs,” says Shultz. “They’re not having to get power off that open spot market in California. So, conceivably, pumped storage might contract with one or more of these utilities as part of that portfolio.”

But that larger and more volatile market, says Schultz, does affect Oregon’s utilities.

The Bonneville Power Administration, he notes, is the most influential player in the state’s energy concern. For most of its existence, the BPA has operated on a business model based upon selling hydropower outside the region, mostly to California, on that more lucrative open market.

It’s used the windfall from those sales to keep electricity rates within the Pacific Northwest low.

But that model won’t be valid much longer if prevailing energy forecasts hold true.

The shifting sands point to the need for the state to engage in planning to figure out which kinds of new energy projects might fit best with Oregon’s future needs.

So is any kind of coordinated plan in the works?

“No,” says Schultz, with apparent frustration. “There’s a lot of buzz around that topic right now. But nothing definitive.”

Uphill battle

In late 2020, Rye sold its Goldendale and Swan Lake pumped-storage projects to Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, a Denmark-based investment firm. Rye has continued to manage the projects.

Erik Steimle is the company’s vice president of development. In a September 2021, podcast hosted by the Oregon Department of Energy, Steimle described pumped storage as “the cornerstone of a Pacific Northwest clean energy economy.” “Pumped storage relies on proven technology, domestic resources and offers a long-term solution to achieve our clean energy future. Our region will not be able to add more solar, wind and other renewable energy onto the grid and maintain grid reliability without a massive amount of additional storage capacity,” Steimle tells Columbia Insight via email. “The integration of intermittent renewables to the grid in lieu of fossil fuel-burning resources will rely on highly flexible, economical bulk energy storage that can respond to swings in demand and help ensure uninterrupted power to homes and businesses. “In today’s economy, pumped storage is the only asset that provides large-scale, cost-effective renewable energy storage capacity and a range of essential grid reliability services. The value of pumped storage will only increase as more intermittent renewable resources are added to the grid in our efforts to meet 100% carbon-free mandates.

“A dearth of evidence, including research used by Pacific Northwest utilities in their Integrated Resource Planning (IRP), clearly prove the economic value of pumped storage.”

Steimle refers to PacifiCorp’s 2021 filing of preliminary FERC permits for 11 pumped storage projects throughout the West as evidence that utilities understand the need for this technology in addition to batteries.

Yet the rest of the country seems to be hitting the pause button on such developments. Around the United States since 2014, 67 new pumped-storage projects have been proposed. Only three have been permitted and none have begun construction.

For Jones, the troubles for pumped storage are beyond purely economic.

“These projects have the potential to be highly disruptive,” he says.

The Goldendale project, when pumping water to the upper reservoir, would consume the same amount of electricity as 770,000 homes, more households than in all of Idaho.

In Jones’s calculations, Goldendale will be a net consumer of energy.

“It’s kind of insane,” he says.

FEATURED IMAGE: Up grade? Proposed pumped-storage project near Goldendale, Wash. The blue circles represent reservoir locations. (Photo: Wash. Dept. of Ecology)

This story first appeared at Columbia Insight. Steven Hawley is a journalist and filmmaker from Hood River, Oregon. He’s covered Columbia Basin power and fish politics for the better part of two decades. The Fred W. Fields Fund of Oregon Community Foundation supported this story.