A new program is helping developers and landowners clean up former orchard lands once doused with dangerous lead arsenate

By Andrew Engelson / Columbia Insight

On a patch of land overlooking north-central Washington’s Lake Chelan and the arid foothills of the Cascade Range, what was once a productive apple orchard is being developed into 20 residential lots. Each lot features a new home.

But before the bulldozers arrived, tests found the soil in this five-acre parcel in the small community of Manson contained high levels of lead and arsenic.

It’s a common problem on former orchard lands in Central Washington.

Apple crops were once drenched in lead arsenate, a pesticide used extensively between 1900 and 1950 to prevent damage from codling moths.

“Building growth in Chelan County is just off the charts,” says Jeff Newschwander, a contamination project manager with Washington Department of Ecology (DOE). “And much of it is on former orchard land.”

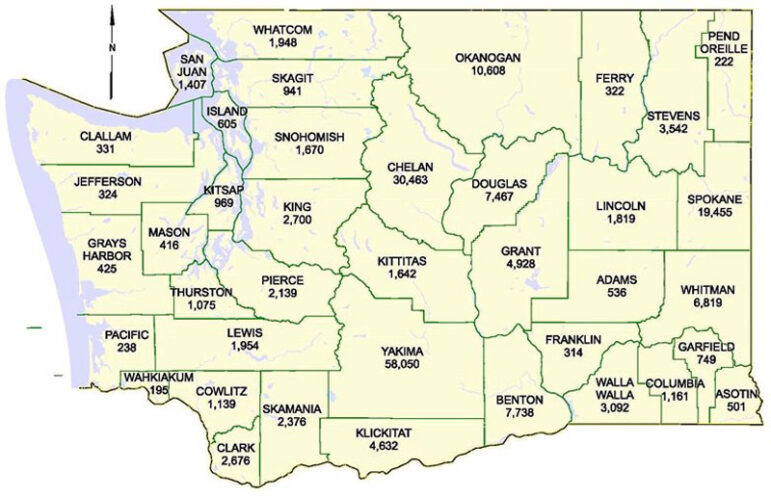

DOE estimates that more than 110,000 acres of former orchard land in Central Washington are contaminated with significant quantities of lead and arsenic, which binds with the soil and remains for decades.

That’s unlike DDT, the dangerous pesticide that succeeded lead arsenate, and which tends to break down and wash away into surface water much more quickly.

To help landowners and real estate developers clean up these persistent poisons, DOE developed a series of “model remedies” to simplify and standardize the cleanup process.

Getting underway in January 2020, the program is one of several to come out of the Legacy Pesticides Working Group, a two-year statewide effort to involve the public in creating solutions to the problem.

The model remedies and an interactive map of former orchard sites were two end results of the working group.

“A model remedy provides assurance that, if you follow the recommended steps, Ecology will buy off on the project,” says Newschwander.

Importing clean dirt

Thanks to the state’s 1989 Model Toxics Control Act, any land that changes use, such as from agricultural to residential, must meet certain standards.

Cleanup has to occur on properties with more than 20 parts per million of arsenic or 250 parts per million of lead.

The five-acre housing development in Manson was remediated late last year as part of a pilot project launched by Chelan County with the help of a $225,000 grant from DOE.

Local developer Telos Construction was able to clean up its Cameo residential development using 2,650 cubic yards of clean topsoil at a cost of about $5,000 for each home lot.

Newschwander says the most common and least expensive restoration strategy to address lead and arsenic is to cap existing soils with clean soil.

That’s sometimes difficult to find in Central Washington. The grant helped Chelan County bring in clean soils for developers at a reasonable cost.

“In places like Manson, there aren’t great commercial topsoil sources,” says Newschwander. “So much of the land there is former orchard that much of the topsoil for sale locally also came from there. And obviously you don’t want to use that.”

Monitoring groundwater

The highest health risks from lead and arsenic in legacy pesticides come from direct exposure to the soil, either by ingestion (such as from home gardens) or from inhaling dust.

Newschwander says DOE hasn’t seen evidence of lead or arsenic leaching into surface or groundwater in significant quantities.

However, a study published in November 2021 in the Journal of Environmental Quality found some wells near former orchard sites in Connecticut showed evidence of increased lead and arsenic levels.

“Groundwater is something we absolutely consider,” Newschwander says in response to a question about that study. “Fortunately, I’ve sampled hundreds of properties, and with most of these properties we’re able to go down and find out where we encounter clean soil.”

Almost without exception, he says, DOE has found the contamination is confined to the top two to three feet of soil.

“I’ve never come across a property where the concentrations in these soils is leachable to the point that poses a threat to groundwater,” he says.

Widespread, persistent, dangerous

Washington’s apple industry grew into the state’s most profitable agricultural crop during the first half of the 20th century thanks to widespread, cheap irrigation and extensive use of lead arsenate as a pesticide. The U.S. Department of Agriculture heavily promoted its use.

Lead arsenate was also used in less intense quantities on cherry and pear orchards, golf courses and home gardens.

As the moths it was meant to control became more resistant to lead arsenate, application on apple trees became even more intense.

For a time, lead arsenate was the most widely used pesticide in the country.

It was phased out of use on most Washington apple crops by 1947, replaced by DDT.

The United States outlawed the application of lead arsenate on all food crops in 1991.

The heavy metals, however, persist across Central Washington and the Columbia River drainage, on former orchards ranging from Yakima to Ellensburg, Wenatchee, Chelan and the Okanogan Valley.

Lead arsenate in Oregon

Lead arsenate was also used on fruit crops in Oregon’s Hood River Valley.

But according to Laura Gleim, a spokesperson for Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), the scale of the problem is much smaller than in Washington.

“Oregon currently has about 5,000 acres of apple orchards, whereas Washington has about 175,000 acres,” Gleim stated in an email.

Unlike Washington, Oregon doesn’t have a mandatory cleanup level for lead or arsenic, so its guidelines are recommendations only. That is unless, Gleim says, “contaminant concentrations are so high that they pose an imminent health threat to people nearby,” and trigger DEQ or EPA investigations.

“Generally, the proposed use of a site is one of the factors DEQ uses when determining cleanup needs and approach,” says Gleim. “For a proposed school, we may request additional data and information about the site if it’s in our program, and we’d default to a more conservative risk value when determining appropriate cleanup.”

In Washington, school properties on former orchards were the first targets for cleanup, with 26 schools eventually being remediated by capping with clean soils, paving over or taking other measures to reduce lead and arsenic concentrations.

“In early 2000 we got funding from the legislature for sampling,” says Newschwander. “We were focused on schools because of longer term exposures, and because young people are more vulnerable.”

Lead and arsenic tend to have adverse health effects when exposure occurs over long periods of time. Children are especially prone to risk, because they often play in dirt and put their fingers in their mouths.

Exposure precautions

According to the CDC, people with prolonged exposure to lead are at higher risk of high blood pressure, heart and kidney disease and various forms of cancer. Chronic arsenic exposure, according to the CDC, can adversely affect the function of nearly all human organs, and is strongly associated with heart disease, diabetes and cancers of the skin, lung and bladder.

Though cleanup isn’t required on Washington lands that aren’t changing use, DOE recommends landowners on former orchards take precautions, including using gloves while gardening, wiping shoes before entering the home, rinsing fruits and vegetables, frequently washing toys used outside and utilizing raised beds for home gardens.

Washington DOE launched an interactive map of former orchard sites in 2021. The maps show sites that were likely used as orchards prior to 1950.

The interactive “Dirt Alert” map also includes extensive records of the results of all lead and arsenic tests on properties in the affected areas, which can better inform landowners of the risks on their properties based on results nearby.

DOE also offers free soil testing to all landowners in potentially affected areas.

Rural resistance

DOE is only beginning to implement its model remedies on a larger scale.

Newschwander says it will take time to get buy-in from local governments and developers.

That will be more challenging in rural communities in Central Washington where citizens tend to be resistant to public initiatives.

“There’s definitely a learning curve for our partners in this process, such as city and county planning authorities and their understanding of what we’re trying to accomplish,” says Newschwander. “We’re doing our best not to put the burden of this process on those local agencies.”

He believes more developers will buy into the program when they realize it’s in their interest to act early on and clean up their properties.

“Ultimately what’s going to be a big driver is when the public becomes more aware,” Newshwander says, “and someone who goes out to buy a new home starts asking questions: Has this been tested? Has this been cleaned up?”

FEATURED IMAGE: Misty mountain crop: Former orchard acres in Washington are being transformed into residential and commercial developments. That means looking at the soil beneath. (Andy Simonds/Creative Commons photo)

This story first appeared in Columbia Insight. Andrew Engelson is a freelance journalist based in Seattle. His writing has appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, Crosscut, InvestigateWest, High Country News, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle Times and Washington Trails. He’s on Twitter at @andyengelson.