The Washington State Patrol this month announced a study had found “no systemic agency bias” in its stops and searches. But that’s not the whole story

Two years after InvestigateWest reported the Washington State Patrol was searching some racial and ethnic groups at a rate one researcher called “disturbing,” the agency has released a new analysis of its stop-and-search data. The headline: “No systematic agency bias.”

The State Patrol and Washington State University researchers who released the study this month, however, acknowledge the problem InvestigateWest uncovered in 2019 persists. State troopers are still more likely to search Black, Latino, Native American and Pacific Islander drivers, even though they’re more likely to find contraband like drugs or weapons when they search White drivers.

“The numbers have improved over the years,” said Chris Loftis, a State Patrol spokesman. “But the improvement has been modest in that particular situation, and modest isn’t good enough.”

In a news release announcing the study, WSU said researchers didn’t find “intentional, agency-level racial bias.” Statewide, they found no evidence that members of Black, Indigenous, Latino and other communities of color were being stopped at a rate higher than their populations and noted “minimal” differences between day and night stops, the latter a more widely recognized metric for determining bias. But WSU’s analysis of more than 7 million State Patrol interactions with the public from 2015 to 2019 found that state troopers stop Black drivers at a rate disproportionate to the Black population in King and Pierce counties, and found a similar disparity for Latino drivers in Benton County.

Christina Sanders, the director of WSU’s Division of Governmental Studies and Services and one of the researchers involved, said that “disproportionality” warrants additional study.

“Disproportionality doesn’t make it biased,” Sanders said. “We’re working with the Patrol to figure out who to talk to next, what kind of data to look at next, what is going on in places we have seen disproportionality.”

David B. Owens, a University of Washington law professor who worked with similar police data in Houston, cautioned against drawing conclusions about the presence or lack of intentional bias or discrimination from a statistical analysis. He said the disparities in stop-and-search rates “support a strong inference of biased policing.” It’s not evidence police are consciously targeting certain races, Owens said, but it suggests race is playing a role — consciously or unconsciously — in the decision to stop and search.

“For there to be some assumed criminality of particular communities does not require an individual officer themselves to be racist,” Owens said. “This is part of the fabric that is woven into police training. This is part of the fabric that is woven into our laws.”

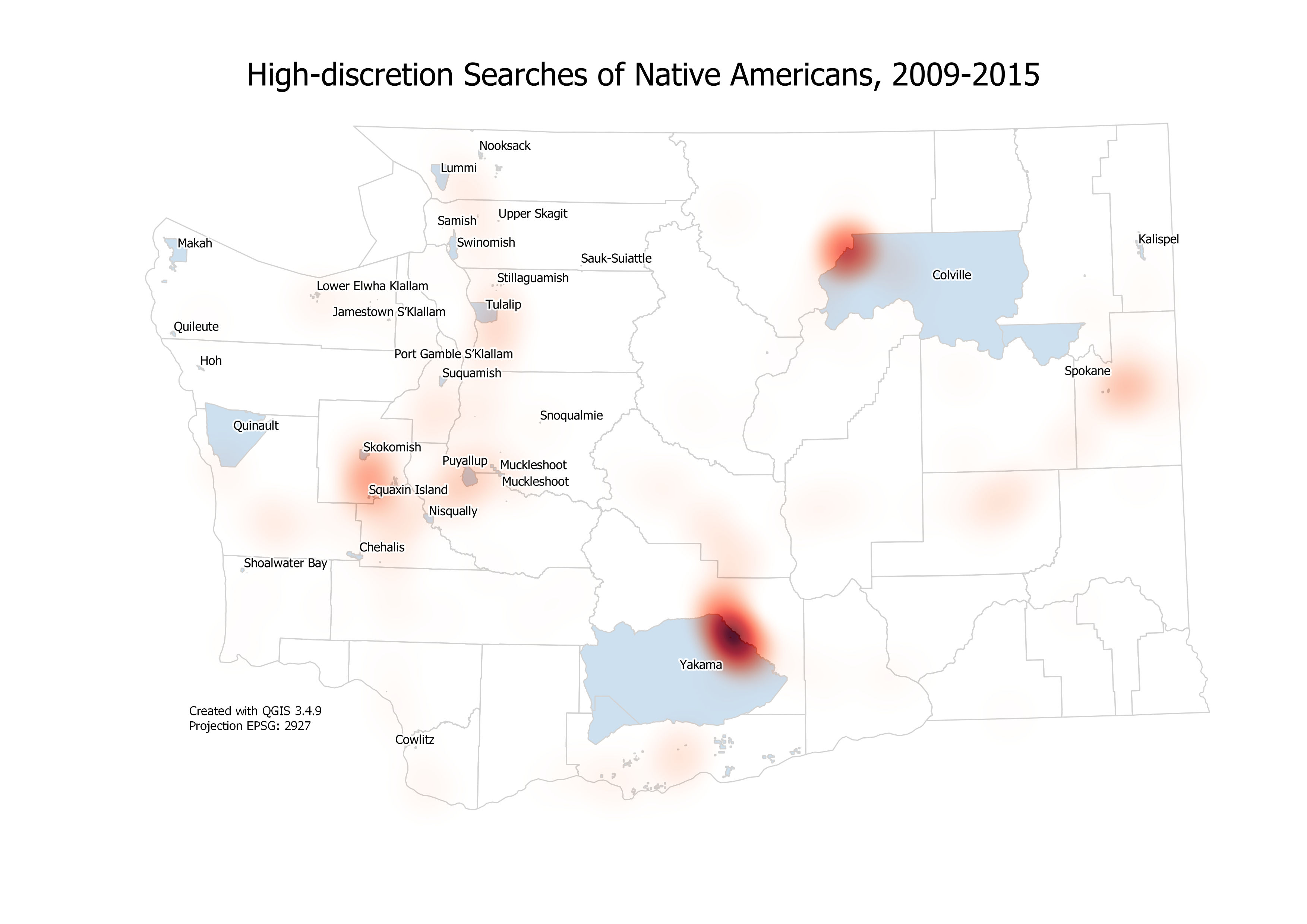

High-discretion searches, such as consent searches or canine searches when policy doesn’t dictate one, are a popular metric for police researchers. There’s a baseline — the demographics of people stopped — against which to compare how often officers search different racial and ethnic groups. When one group is searched at a higher rate than another, but the “hit” rate — the likelihood of finding contraband — is lower, it suggests police are setting a lower bar to justify searching members of that community.

WSU found that troopers were nearly five times as likely to search Native American drivers as they were White drivers, slightly better than InvestigateWest’s findings from 2009 to 2015. When WSU researchers took into account other factors like gender, traffic violations and time of day, the disparity decreased. Taking into account those factors, Black drivers were 1.16 times more likely to be searched than White drivers, Latino drivers were 1.58 times more likely to be searched and Native American drivers were 2.77 times more likely to be searched. The State Patrol isn’t alone. Stanford University researchers, whose data InvestigateWest used for its analysis, have found similar problems across the country.

Experts said those disparities result in an unequal application of the law — White drivers are less likely to face consequences for illegal activity — and drive a wedge between police and the communities they serve. That can spill over into other areas of policing.

“The reason these communities are interacting with police is because they’re being stopped more,” Owens said. “If you can reduce negative police interactions on the front end, you can reduce the chances those negative interactions result in use of force or violence.”

Clay Mosher, a WSU sociology professor who was not involved in the most recent study but conducted similar analyses in the past, said it’s “a good thing” the state is renewing the studies. He agreed with the finding that there’s no evidence of statewide discrimination by troopers. Still, Mosher acknowledged, the State Patrol is more or less where it was almost 15 years ago when he and colleagues recommended investigating the search-rate disparities. Loftis said the agency abandoned those studies in 2007 because of lack of funds.

“The next step is to try to drill down into the data and look at individual troopers,” Mosher said. “Are there troopers within particular counties who are more likely to search than others? And if so, what do they look like and what’s the reason for that? To me that’s the next kind of logical step in this, which we never really got to either.”

Sanders said WSU will conduct focus groups around the state in an effort to better understand the disparities. She said researchers will work with the State Patrol to collect data that is easier to analyze and seek input from its leadership about “how best to follow up.”

Norma Sanchez, a Colville Tribal Council member, points out where she says in 2017 she saw three state troopers stopping cars near where tribal land overlaps with the city of Omak in north central Washington. InvestigateWest’s 2019 analysis found nearly one-third of all high-discretion searches of Native Americans by the Washington State Patrol happened where U.S. 97 entered the Colville and Yakama reservations. (Jason Buch/InvestigateWest)

“I think what we’re going to have to do probably is start looking at different locations and analyze that on a local level,” Sanders said. “The State Patrol collects a lot of data already. I’m not sure they’re going to need to collect more data, but (collect it in) a format easier to convert to analysis.”

State Rep. Gina Mosbrucker, the Goldendale Republican who authored legislation funding WSU’s study, praised the State Patrol’s performance as well.

“Overall I’m really happy with the results, and I do honestly believe they’re willing to train or do whatever they need to,” Mosbrucker said.

Mosbrucker, the ranking member of the House Public Safety Committee, said she supports WSU’s plans to hold focus groups. But she called the continued search-rate disparities “concerning.”

“I do think they need to investigate more,” she said. “I think the answers are with those who are most affected.”

In 2020, the Legislature also gave the State Patrol, whose commissioned officers are nearly 90 percent male and 90 percent White in a state that’s only 61.6 percent White, funds to conduct a diversity study. That report, released in March, criticized a hiring process that doesn’t attract a diverse enough pool of recruits and a psychological evaluation process that resulted in “disproportionally high fail rates for people of color.”

State Rep. Javier Valdez, D-Seattle, said he’ll be working with Gov. Jay Inslee to set benchmarks for the State Patrol to improve its diversity and address disparities in search rates.

“If we’re going to build trust in our communities throughout the state, and especially for people of color to build that trust with law enforcement, the numbers need to show people of color aren’t being targeted at a disproportionate rate,” said Valdez, who authored legislation funding the diversity study.

Loftis, the State Patrol spokesman, said over the last two years the agency has hired a diversity, equity and inclusion director, begun contracting with an outside firm to conduct psychological evaluations, and pledged to have 30 percent female recruiting classes by 2030 — right now about 10 percent of recruits are women.

“One thing the study points out is that disproportionality is not in itself an indicator of racial bias,” Loftis said. “In absence of evidence of bias, we are diligently looking through each possibility, but we have not and will never abandon the idea that we must always search for bias and eliminate it however and wherever it is found.”

Joy Borkholder contributed to this report.