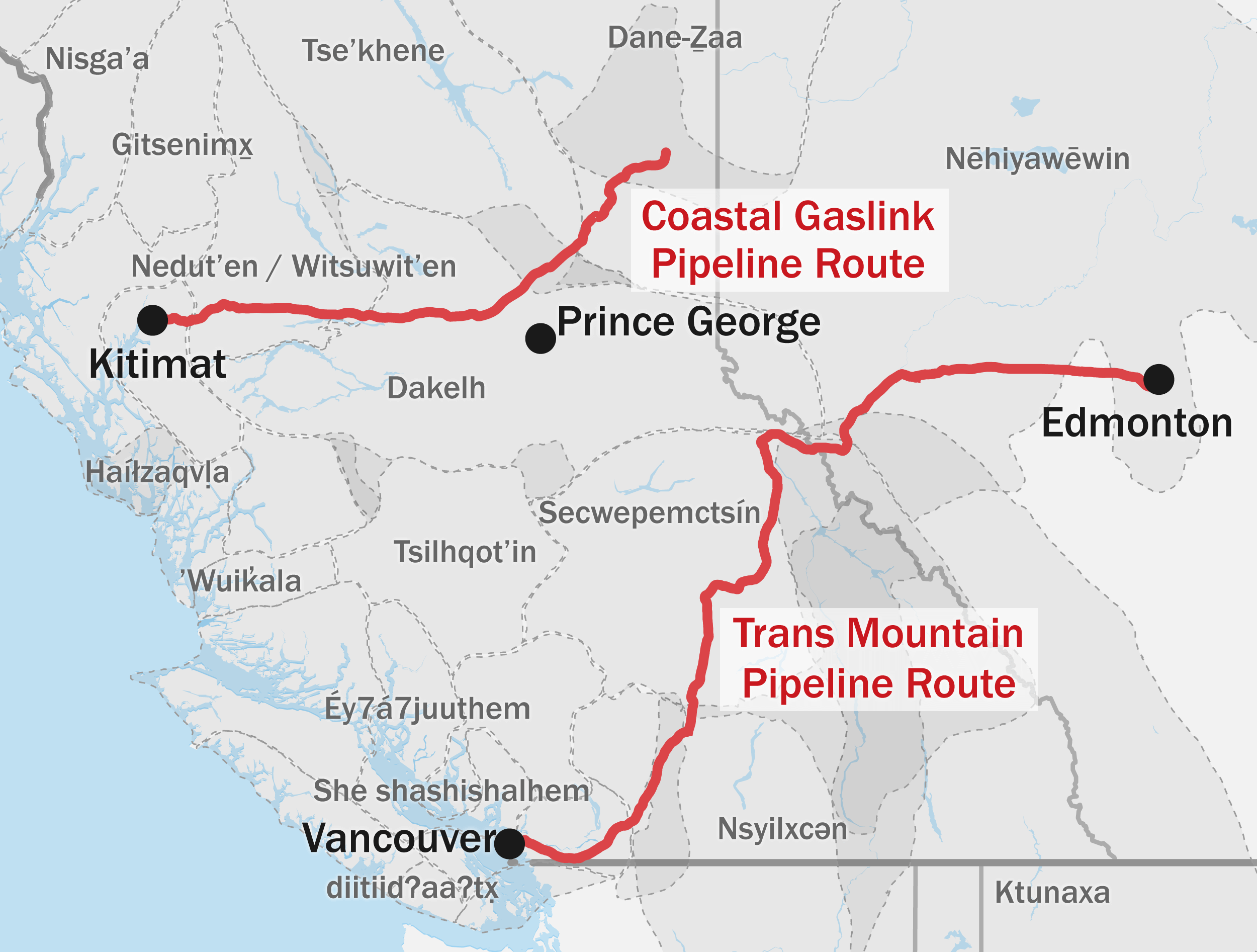

While most protests against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion are happening on the land, the federal government has recognized that some of the project’s greatest risks concern potentially catastrophic spills on the water.

While most protests against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion are happening on the land, the federal government has recognized that some of the project’s greatest risks concern potentially catastrophic spills on the water.

That’s because the expansion is expected to spur at least a sevenfold increase in the number of oil tankers plying the waters of the Salish Sea, the body of saltwater shared by British Columbia and Washington state.

The Trans Mountain project includes three new tanker berths at its terminal in Burrard Inlet, on Burnaby’s northern shore. Charlene Aleck, a spokesperson for Tsleil-Waututh Nation’s Sacred Trust Initiative, which is fighting the Trans Mountain expansion, says the tanker traffic is essentially in her kitchen.

More than 90% of Tsleil-Waututh’s diet came from Burrard Inlet before settlers arrived, yet today community members consume very little from the inlet due to industrial pollution.

The Tsleil-Waututh Nation has recently cleaned and restored a degraded clam garden in the inlet and has since hosted three successful clam harvests.

“We’re able to maintain our Indigenous way of life, to be able to hand those skills down from grandmother to mother to daughter to granddaughter,” said Aleck.

The increased tanker traffic and elevated risk of an oil spill from the Trans Mountain expansion will “decimate” this project, she says. A recent Tsleil-Waututh report found that tugboats and tankers increase wave energy in Burrard Inlet, eroding nearshore ecosystems and “irreplaceable” archaeological sites.

Legal maneuvering over such marine impacts continues, in spite of a crushing defeat last year.

Tsleil-Waututh led a legal challenge that delivered a milestone victory for the anti-pipeline coalition in 2018, when a federal court overturned Trans Mountain’s federal approval. The decision cited the Canada Energy Regulator’s disregard for marine impacts from increased tanker traffic as well as insufficient consultation with Indigenous communities.

But in 2019, the regulator endorsed the project again, subject to more than 150 enhancements in safety, preparedness, environmental regulation and community engagement. And last year federal courts approved the package.

Still, pipeline opponents keep pushing. A recent gambit led by the Squamish Nation, northwest of Vancouver, seeks to exploit a 2019 British Columbia court order that requires Premier Horgan’s NDP government to reevaluate environmental approvals awarded to Trans Mountain by the previous government.

Last month B.C.’s environmental regulatory agency proposed two tweaks for public comment, and the province expects to complete its reconsideration of Trans Mountain’s approvals by early summer. Cities, environmental groups and First Nations are pushing for more.

One tweak would require Trans Mountain to issue reports every five years detailing research that it is mandated to conduct on the behavior and recovery of spilled diluted bitumen. The second would require reporting on how marine spills could harm human health, including various pathways people could be exposed to spilled oil and solvents from Trans Mountain and ways to reduce those exposures.

“It doesn’t go far enough. It doesn’t go deep enough,” is how Andrew Radzik, energy campaigner with the Nanaimo, B.C., and Vancouver-based Georgia Strait Alliance, described the proposal. He said the province should specify objectives for the diluted bitumen spill studies, such as how seasonal conditions will impact what happens during spills, and require public consultation on those reports.

For the health report, he called for explicit inclusion of mental health impacts, and for detailed reporting on how Trans Mountain will cover the cost of efforts to reduce identified health hazards to oil spill responders and coastal communities.

He also called for a shoreline response plan. It could clarify who will battle a spill at the shore and how they will be equipped and trained.

Radzik said that he feared the provincial government would shy away from such strengthened requirements that could increase costs and add delays to the project. “They can’t stop the project, but they can meaningfully impact it. They seem to not want to.”

Feature image credit: Mark Garrison

This story is supported in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.