With summer still weeks away, Washington’s fire season is shaping up as onerous — and in this pandemic year, especially dangerous.

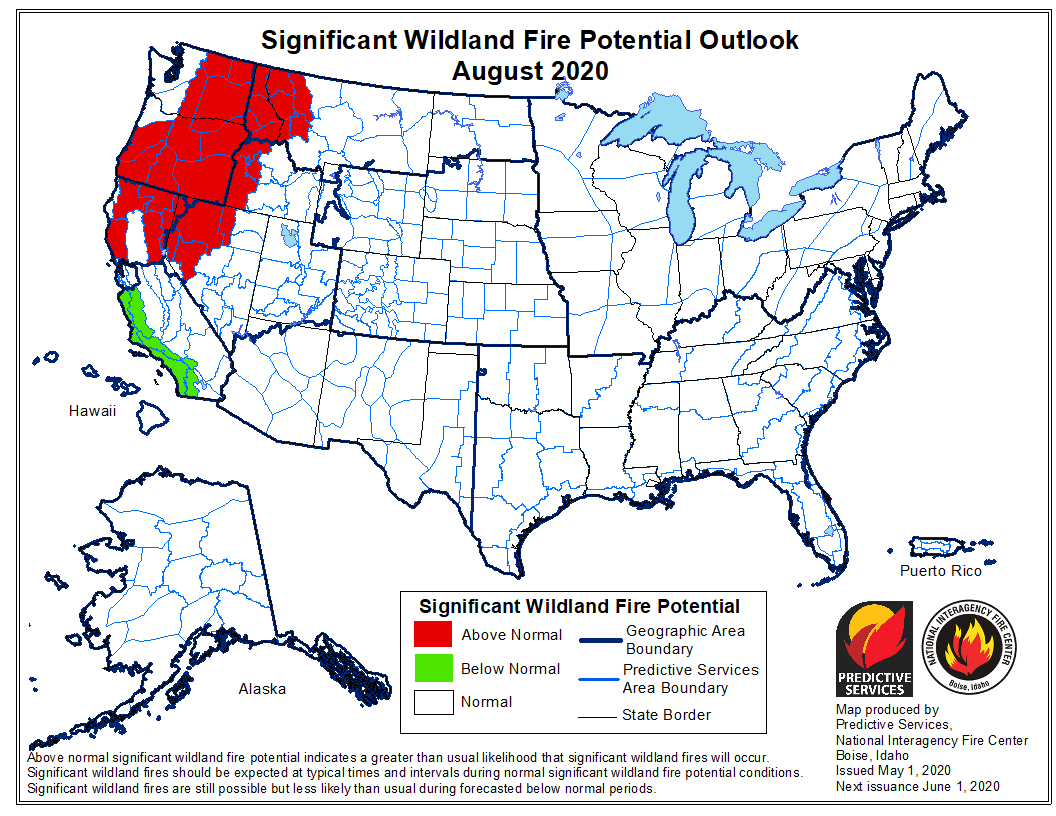

Hotter than usual temperatures are forecast and more than half of the state is in or near drought. Summer fire forecasts for Washington and Oregon are the worst in the nation. And 2019 was a light fire year, leaving a particularly heavy buildup of underbrush that can fuel backcountry blazes this summer.

Already this year, Washington has seen nearly triple the usual number of wildfires, said Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz, who, as head of the Department of Natural Resources, leads the state’s wildfire response. While some of that uptick can be attributed to homebound residents’ enthusiasm for burning away brush in the countryside, the increase is worrisome.

Already this year, Washington has seen nearly triple the usual number of wildfires, said Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz, who, as head of the Department of Natural Resources, leads the state’s wildfire response. While some of that uptick can be attributed to homebound residents’ enthusiasm for burning away brush in the countryside, the increase is worrisome.

“This year is looking like it’s going to be a tough one,” Franz said in a recent phone interview.

And then there’s coronavirus.

As with grocery shopping, dating and so many aspects of American life, the pandemic has injected a new complexity into firefighting and made business as usual unreasonably risky.

In America, large fires are fought from fire camps. Those camps amount to sprawling tent cities thrown up at county fairgrounds, empty fields, shuttered campgrounds and the like. Crews mix at chow tents and showers, swapping trucks as needed and rotating out after 14-day stints near the fire line. Fire managers, bookkeepers and IT workers mingle among them.

Cold Springs Fire at dusk on July 13, 2008, with firefighters’ tents in foreground and Mount Adams in background. Because camps like these make it easy for disease to spread, agencies are planning to have firefighters camp in small groups for the 2020 summer fire season, but this could cost them basic amenities like hot food and showers.

It’s an environment primed for disease to spread, and one that can’t safely exist until coronavirus has been contained.

The plan instead, put forward by state and federal land managers, would have firefighters segregated by units or vehicles and directed to camp in small groups, creating physical separation that, it is hoped, coronavirus cannot cross.

Already in Washington, state firefighters have been put up in hotels instead of tents, Franz said.

The U.S. Forest Service and state land managers also say their focus will be extinguishing fires early, before they grow large enough to necessitate hundreds of firefighters. The practice, known in fire circles as “initial attack,” has long been a staple of American wildland firefighting, and some longtime firefighters don’t see much room to expand it.

Firefighter recruiting is down due to coronavirus and preventative burning to clear out underbrush was widely curtailed this spring for the same reason. That left land managers with a smaller, less effective firefighting force and forests unusually vulnerable to fire. Will the virus mean fires that would otherwise be fought are left to burn?

“It is possible that we will choose to put out all fires. It’s also possible that we will choose certain fires to not put out, because the risk of exposure is too high,” said Tom Zimmerman, a retired federal firefighter and former president of the International Association of Wildland Fire. “There’s not a simple answer.”

Recent incident reports following fires across the West illustrate the difficulties expected to intensify as fires spread.

Firefighters in New Mexico and Colorado described workers from various agencies mixing freely at the fire scene, heedless of social distancing directives. A review following an April 23 fire in a coronavirus hotspot in Idaho estimated staffing levels at 75% of normal, as career firefighters opted to stay home. At the time, Blaine County, where the fire was located, had the fifth-highest rate of COVID-19 in the country, surpassing rates recorded in New York City and Italy.

Firefighter Steven Thime hops onto a tree stump to survey the progress of a prescribed burn in 2019 in Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest near Liberty, Wash. Preventative clearing of brush by so-called “prescribed burns” like this was widely curtailed ahead of this pandemic year’s fire season due in part to social distancing challenges.

“I also have two kids that frequently visit grandparents who are in the high-risk category for the illness,” one firefighter told reviewers. “My personal risk seemed to be more of a factor for me in my decision.”

Coronavirus presents a particular danger to firefighters exhausted from the fire lines, their lungs routinely dusted with the combination of smoke and ash known as “camp crud.” It also injects new complexities into what was already a challenging calculus. The priorities — protect lives and homes, then timber and property — remain the same, and state and federal officials say fires that threaten communities will be fought.

Managers may find themselves resource-limited if the fire season proves intense. The Forest Service has committed, nonetheless, to fighting all fires on lands it manages.

“Firefighters will respond to every wildfire, but to prevent the spread of COVID-19, how they are mobilized and supported will be different this year,” said Lisa Bryant, a spokesperson for the Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station at Fort Collins, Colorado.

Like their federal counterparts, state fire managers in Washington and Oregon aim to attack fires early in the hope that they can limit the number of sprawling burns that consume tens of thousands of acres and draw in thousands of firefighters. Franz said Washington has upped its “air game,” fielding 12 helicopters that empty large water tanks over fires and contracting for planes equipped to dump fire retardant.

Facing fire, coronavirus with imperfect fixes

Since the pandemic set in, a search has been underway to find safe-enough firefighting schemes. Land managers and longtime firefighters have joined with modelers and researchers in the effort, the first fruits of which have been incorporated into region-specific plans.

It is not at all clear how damaging coronavirus can be for firefighters, but it’s been shown that smoke inhalation eases the transmission of viruses. Research indicates that small increases in air pollution drive an outsized increase in COVID-19’s fatality rate.

A draft version of a Forest Service brief made waves in Washington, D.C., after a group of senators noted in a letter to the agency that the paper considered fatality rates as high as 6% among infected firefighters. The Forest Service and researchers involved in the study say that hypothetical fatality rate, used to develop a worst-case model, was misconstrued as a finding.

“It is important to understand that the figures in this report are not predictions, but rather … possible scenarios,” Olivia Walker, a Forest Service spokesperson based in Washington, D.C., told InvestigateWest. The Forest Service expects to release a final version of the brief soon.

Jude Bayham, a Colorado State University environmental economist involved in the modeling work, said the effort aimed to determine which changes make fire camps less vulnerable to the pandemic.

“We have potentially thousands of people in close proximity, stressed emotionally and physically, under conditions of relatively poor hygiene,” Bayham said. “That mixed with what we understand about this disease right now is concerning. …

“I don’t have any faith that we can exactly predict the number of cases or infections or anything like that, but what I hope is we can highlight big differences” in the impact various precautions will have.

The nature of any given fire dictates which steps are best suited to stemming the disease’s spread, Bayham said. In short, in cases of intense fires lasting a day or two, the models showed that screening firefighters for fever or, if possible, testing them for coronavirus is key. Doing so keeps the virus from jumping between fire agencies, and prevents firefighters taking coronavirus home.

Longer fires draw dozens or hundreds of firefighters who cycle through on 14-day rotations. In those situations, Bayham said, creating physical distance between people and isolating units from one another can stop the disease from spreading through the whole firefighting force.

To slow the spread, firefighting units — an engine crew of two, a backcountry firefighting team of 20 — will segregate like households have since the pandemic arrived, Oregon Department of Forestry spokesperson Jim Gersbach said. They’ll eat together, bunk together, and mix with others as little as possible.

“You stay in your tent, or you stay in your vehicle,” Gersbach said.

Spreading fire crews around will likely cost firefighters basic amenities that on a fire line feel like luxuries. Hot food and showers may not be available, and some crews may have to subsist on self-heating military rations.

Dispersal also complicates the work of organizing a safe fire response. Zimmerman, the retired federal firefighter, said those challenges will intensify as fires grow.

“You can break up smaller camps and do that, until we get into the very worst part of fire season,” said Zimmerman, who currently works with the Association for Fire Ecology, a leading fire science organization. “Then I think the difficulty increases significantly because you need a lot more logistical support to support more camps at the same time.”

It’s envisioned that firefighters will be screened daily for fever, and tested for the virus if tests are available. The degree to which firefighters will be able to shift state-to-state or country-to-country — Australians were on Washington fire lines in 2018 — will be curtailed. Training has been cut back at the state and federal levels.

Across the West, fire services aim to focus on fast, low-headcount efforts to extinguish fires right away before they spread.

Firefighters battled to contain the 90-acre Rogers Fire on Mount Rogers in the Colville National Forest, five miles west of Aladdin, Wash,. in August 2011. Mop-up crews ensured that no flare-ups occurred.

Federal and state land managers have long relied on quick, decisive responses to knock out most fires, said Michael Liu, a longtime Forest Service firefighter who retired as the Methow Valley District ranger in 2018. Liu questioned how much more could be done. While firefighting has been restricted in protected areas like the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in the Central Cascades, fast firefighting already is the norm in most forests.

For decades, “the Forest Service and other agencies already have pretty good protocols in terms of initial attack,” Liu said, “so I don’t know that an aggressive initial attack strategy is going to make much difference.”

The style of response will be fire-specific, and shaped by forces far from the fire line, said Bethany Hannah, a former Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management firefighter involved in an international survey of firefighters, land managers and others aimed at identifying disease-control practices.

“It’s going to be a very fluid situation, and they aren’t going to apply a single approach to all areas,” Hannah said.

Hannah said her concern is first for the firefighters. While she has retired from firefighting, her husband will be on the West’s fire lines this summer. Beyond that, though, she worries that a return to aggressive firefighting may outlast the coronavirus, that fire management will return to the practices that set the stage for the extremely large fires that have become increasingly common.

“We need to keep progressing in how we approach fire and live with fire, and that can’t be done if we suppress all fires,” Hannah said. “There’s a classic saying, we’re not putting fires out, we’re putting fires off.

“Fires are going to burn.”

This story was funded in part by the Sustainable Path Foundation.