This story is produced in partnership with Columbia Journalism Investigations, the Center for Public Integrity, and InvestigateWest

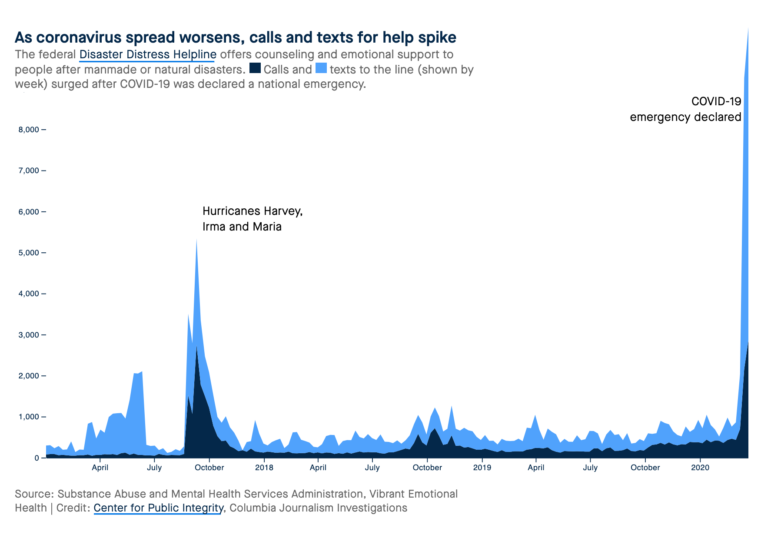

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, calls and texts to helplines are surging to levels that might be unprecedented, certainly in recent memory.

The number of Washingtonians who reached out to the federal Disaster Distress Helpline in March jumped almost sevenfold – nearly matching the entire years of 2018 and 2019 combined, according to data obtained by the Center for Public Integrity and Columbia Journalism Investigations. The helpline (1-800-985-5990) fielded 718 calls and text messages from Washington State and more than 26,000 nationally, more than an eightfold increase.

The surge was felt by other helplines as well. Allie Franklin of Seattle-area Crisis Connections says a 73 percent jump in calls to the King County 211 community resource line in March was fueled in part by hourly workers who lost hours following government restrictions, asking: How will I pay my rent? How am I going to feed my family?

“We have a lot of first-time callers to 211 who are saying, ‘I’ve never used a food bank before. I don’t know what I need to bring with me. I don’t even know how to access that. What do I do?” Franklin says, adding that some express remorse, saying, “I’m sad that I have to do this. I take a lot of pride in being able to support my family.”

In March, after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency, calls and texts to the federal Disaster Distress Helpline jumped nearly sevenfold, fielding 718 calls and text messages from Washington State and more than 26,000 nationally, more than an eightfold increase.

Franklin says she has noticed what she calls “the Gov. Inslee effect:” Each time Washington Gov. Jay Inslee announced a new round of restrictions, the 211 line lit up with an uptick in anxious callers. First, school closures prompted concerns from parents over how to work when the kids are home. Then the ban on dining in restaurants, and then bar closures, put countless employees out of work before stay-at-home orders hit the entire state. Helpline staff in March worked overtime to handle 35,000 calls, up from the typical 20,000, to tell callers how to access help with housing, food, legal aid, social support and other basic needs.

“This is affecting ALL people, right? All people are needing extra support right now,” Franklin says. “Not only is it okay to reach out and to get support, but the support is there specifically to help people who are in these kinds of situations.”

Signs of distress abound. Calls to the 24-hour Crisis Line in King County (1-866-427-4747), also handled by Crisis Connections, rose in March by about 25% over normal, to 19,165 calls. A bigger deal, says Franklin, is these calls now tend to last longer – turning a 15-minute conversation into 30 minutes, a 45-minute call into an hour. That’s partly because the hotline works collaboratively with callers until reaching a safe resolution, which nowadays can entail explaining what may be new ideas such as trying telemedicine instead of in-person doctor visits or Zooming with friends instead of outings.

“We’re getting folks calling with a higher degree of distress,” says Franklin. She adds that “some of these folks, they’re feeling really isolated.”

What may be the initial reason for the crisis call – “I’m feeling hopeless” or maybe “I’m feeling suicidal” – can evolve as the call continues, leading to specific worries about eviction, feeding the family or maybe domestic violence, Franklin says. The National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233) reportedly has nationally fielded at least 2,345 calls related to the new coronavirus. Locally, the Seattle Police Department in March saw a 21% year-over-year rise in domestic violence calls, to 1,010 total, the vast majority of them arguments instead of actual crimes, said Detective Patrick Michaud.

“The message to ‘stay home’ will, of course, be terrifying for victims of domestic violence,” Michaud said via email. “Resources will be harder to access, and existing anxiety and fear will be compounded by this new global crisis. “Social distancing can magnify the feelings of isolation that domestic violence survivors may already be experiencing,” Michaud said.

“This is an important time to encourage friends, family and community members to reach out and support each other in new and creative ways. Reaching out to let someone know they are not alone can be incredibly helpful to break isolation.”

‘THIS FEELS DIFFERENT’

“This feels different, and it is,” said Roxane Cohen Silver, a professor of psychological science, medicine and public health at the University of California, Irvine. “This is an invisible threat: We don’t know who is infected, and anyone could infect us. This is an ambiguous threat: We don’t know how bad it will get … we don’t know how long it will last. And this is a global threat: No community is safe.”

Dozens of studies link psychological burdens with isolation and crises, including epidemics. In one study of the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Hong Kong in 2003, nearly half of surveyed residents said the experience weighed on their mental health. Sixteen percent showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, six months after the outbreak ended.

Sarah Lowe, a psychologist and assistant professor at Yale School of Public Health, calls the coronavirus a “slow-motion disaster” with potentially widespread and persistent mental-health fallout. Lowe, who studies the effects of disasters, said she worries that some people will be disproportionately affected, particularly medical workers, the sick, those with pre-existing mental illness and anyone facing economic challenges.

“We know from previous disasters that long-term financial strain tends to be associated with depression and PTSD,” she said.

Laila Brown fields calls at Crisis Connections headquarters. Staff are working overtime and more volunteers are sought to deal with an unprecedented number of callers.

More hopeful is Peter Rosencrans, a therapist and doctoral student at University of Washington Department of Psychology’s Center for Anxiety & Traumatic Stress.

It’s normal to be anxious during a pandemic, he assures, and feel like your mood is more variable than usual. Anxiety is a response to a perceived threat to our safety. Feeling sad or anxious in and of itself is not dangerous. They’re temporary reactions. Just remind yourself: It’s normal to feel this way. That reminder can be comforting in itself. “We cope with these extremely difficult stressors, generally speaking, much more effectively than we might expect,” Rosencrans says.

When the pandemic is over, research suggests the most common response we’re likely to have by far is resilience, Rosencrans says, as opposed to, say, PTSD. Improving the odds with strong social support – via virtual social gatherings or calls with people you care about – helps. So does finding safe things you can do to bring you joy, such as going for a walk or run, or finding new ways to have fun with friends online. Or making a positive difference in other people’s lives by donating time or money to the many organizations in need, for instance. Resilience is his watchword. “I think that is extremely reassuring,” he says, “personally.”

Still, like the federal hotline, the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ HelpLine is seeing a surge in calls. Before COVID-19, the illness the new coronavirus causes, 150 calls would be a big day, said Dawn Brown, the HelpLine director. Now, the daily average surpasses 200 calls and 50 emails, with nearly half of callers mentioning the virus. Relatively few come from Washington state; Brown’s figures show the volume nearly tripled after March 1 to nearly three calls a day.

Callers to NAMI’s line (1-800-950-6264) are sharing feelings of anxiety and depression as well as asking for advice about how to continue mental-health treatment and get medicine refilled during stay-at-home orders.

“People with mental illness require a great support system,” Brown said. “They don’t do well with uncertainty and ambiguity, which this has certainly caused. Just when you think you’ve got a handle on it, something else happens, whether it be a shelter-in-place order or more news coverage talking about death and shortages.”

And the number of people taking a free screening test for anxiety offered online by the advocacy organization Mental Health America grew more than 20 percent from mid-February through mid-March, compared with the early part of the year. That’s the COVID-19 effect, said Paul Gionfriddo, the group’s president and CEO.

He’s worried the country may be underreacting to the mental-health toll. “And it’s only going to get worse as we have to bring widespread grieving into the equation as more people die,” he said. “Because people will be grieving alone.”

Some federal and state health authorities are rushing to maintain psychological support. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has expanded access to teletherapy, including for Medicare, and some states are waiving telemedicine restrictions for Medicaid. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration is now allowing doctors to prescribe medications virtually without having to first meet a patient face-to-face.

What officials say in this fraught period also can help, or harm, mental health.

“Not every message from public health leaders will be comforting,” said Brian Hepburn, who leads the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. But consistent messaging will build trust, he said, and as a result “you are going to see a decrease in fear, in those spikes.”

The first uptick in calls to the Disaster Distress Helpline, both from Washingtonians and nationally, happened on March 16, the same day President Donald Trump announced recommendations such as closing schools and avoiding gathering in groups of more than 10 people. Six days earlier, he assured Americans that the administration’s response was “really working out” and downplayed the threat by saying deaths were minuscule compared with the flu.

Lowe said she was upset to see the president’s March 20 press conference, in which he criticized a reporter who asked, “What do you say to Americans who are scared?” Trump rebuffed the question, calling the reporter “terrible.”

“I found that invalidating of people’s fears and worry,” Lowe said. “People are afraid. Denying that will only make those feelings intensify.”

Helplines and crisis hotlines are only an initial support system for people in emotional distress. Gionfriddo, of Mental Health America, is urging people — and elected officials — not to assume the anxiety and other corrosive effects will disappear on their own when the pandemic is over. The amounts of mental-health funding in Congress’ coronavirus package, he said, “are rounding errors,” money that in his view will not be enough to address the surge in needs.

“If we make them an afterthought — if we don’t address them aggressively — they’ll still be there,” he said.

Dean Russell is a reporting fellow for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School. Funding for CJI is provided by the school’s Investigative Reporting Resource and the Energy Foundation. Jamie Smith Hopkins is a reporter and editor at the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative newsroom in Washington, D.C. Sally Deneen, an independent journalist on assignment for InvestigateWest in Seattle, localized the data and story.