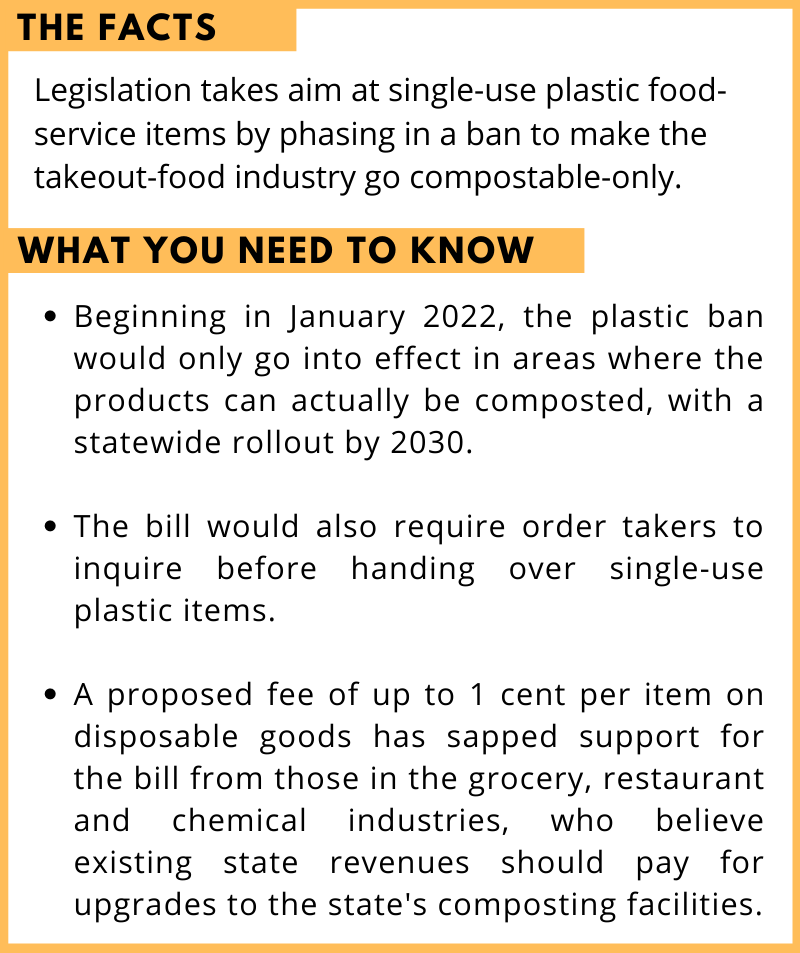

OLYMPIA — Amid worries about mounting environmental and public-health costs of cheap, disposable plastic, Washington lawmakers are proposing a prohibition that would see the state’s takeout industry go compostable-only.

Legislation under consideration would create a phased-in ban on plastic “food-service products” accompanying ready-to-eat food — a lengthy list of items that includes containers, bowls, bottles, meat trays, produce sacks, utensils, tea bags and sandwich wrap. It would also impose a penny-per-item fee on disposable goods to fund a multi-million-dollar upgrade to composting facilities in the state, most of which can’t process compostable utensils and containers.

Legislation under consideration would create a phased-in ban on plastic “food-service products” accompanying ready-to-eat food — a lengthy list of items that includes containers, bowls, bottles, meat trays, produce sacks, utensils, tea bags and sandwich wrap. It would also impose a penny-per-item fee on disposable goods to fund a multi-million-dollar upgrade to composting facilities in the state, most of which can’t process compostable utensils and containers.

The ban’s impact would first be felt in King and Snohomish counties, the only counties in the state with facilities capable of handling compostable food-service items. The plastics ban, slated to begin in January 2022, would only go into effect in areas where those products can actually be composted. By 2030, the restrictions would apply statewide.

The grocery, restaurant and chemical industries have opposed aspects of the bill, and are particularly dissatisfied with the fee. They contend existing state revenues, including a tax on takeout containers, should pay for modernization.

Public concern over plastic waste has already prompted action by local governments in Washington, similar legislation in other states and broad bans in Canada, the European Union, Taiwan and China. In an interview, Rep. Mia Gregerson, lead sponsor of House Bill 2656, said the fact that whole nations have stepped back from disposable plastic shows that a state like Washington can manage it.

“We can’t recycle our way out of this crisis,” the SeaTac Democrat said. “We can’t organize each individual city one at a time and work our way out of this. We have to be the adults in the room.”

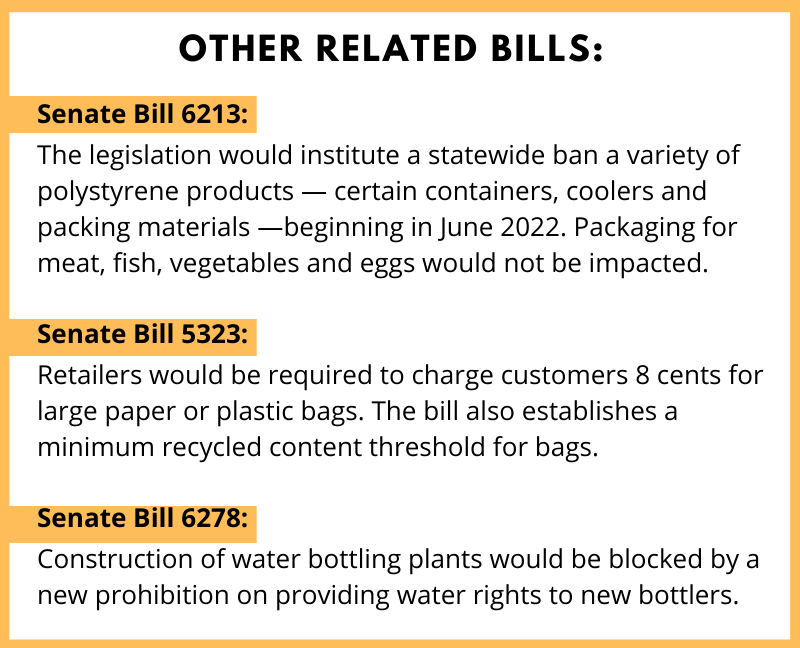

Democrats in Congress, including Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Seattle, are sponsoring legislation that would partially ban disposable plastic while upgrading America’s solid waste infrastructure. The federal legislation, which has not drawn any Republican co-sponsors, would phase out many single-use items while creating a national bottle and can refund program, establishing a fee for carryout bags and pausing construction of new plastic manufacturing plants.

“Plastic production is a major driver of pollution accelerating the climate crisis,” Sen. Jeff Merkley, an Oregon Democrat, said in a prepared statement announcing the legislation, called the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act of 2020 earlier in February. “An America innovative enough to create a million uses for plastic is innovative enough to create better alternatives.”

Only about 8% of the 35 million tons of plastic produced annually in the United States is recycled, and about 303,600 tons of America’s plastic waste winds up as litter just in the zone within about 30 miles from the coast. Plastic may also pose a public health threat; high levels of “microplastics” released as plastic degrades are almost always found in American drinking water. And the situation has become a bit gross — a recent study at University of Newcastle, Australia, commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature, found most people consume a credit card’s weight in plastic each week.

Having encountered opposition over the fees, Gregerson’s bill may not reach the House floor. Its next test is a possible vote Thursday in the House Appropriations Committee.

Having encountered opposition over the fees, Gregerson’s bill may not reach the House floor. Its next test is a possible vote Thursday in the House Appropriations Committee.

The most noticeable change put forward in Gregerson’s bill is also its least controversial. The legislation requires order takers to inquire before handing diners straws, utensils or condiment packs. The idea is that, if asked, some Washingtonians will decline in order to reduce waste.

Less obvious to consumers would be the new fees, up to a penny depending on whether the item is recyclable or compostable. Fees would be paid by the company that buys the item; customers wouldn’t see a new charge on their receipts.

That penny-per-item fee has sapped support for the legislation, said Rep. Mary Dye, a Pomeroy Republican deeply involved in negotiations on the bill.

In an interview, Dye lauded aspects of the legislation but said she could not support the fee. As she described it, the fee would have an “egregious impact” on farmers preparing ready-to-eat food like hard-boiled eggs.

“People don’t recognize how the money flows in the food industry, but the farmers themselves don’t have a lot of ability to negotiate the price for their products,” Dye said. “It costs money to process their product and prepare it for sale, and that cost is borne by the grower.”

Lobbyists for the grocery and restaurant industries are asking that the fees be cut from the legislation. To-go containers are already taxed to fund a state anti-litter program, and industry representatives note that per-item fees grow rapidly when levied on boxes of forks and stacks of cups.

“It may seem like it’s just a penny, but it gets [big] in a hurry,” said Holly Chisa of the Northwest Grocery Association.

All those pennies add up to revenue for the state; the fee is predicted to generate about $18 million in 2023, the first full year it is collected, and that sum is expected to rise steadily each year through 2030. Significant operating costs of more than $1 million in the program’s first year are expected to shrink as the program rolls forward.

The Washington Legislature is considering requiring the state’s takeout industry to use only compostable cutlery such as these. Initially, in 2022, it would go into effect in King and Snohomish counties, where there are facilities to compost the material.

That revenue would fund improvements to composting facilities in the state, facilities that proponents note have ample room for improvement.

At present, nine of the state’s 13 compost facilities don’t process compostable food packaging and utensils. Plant operators have been reluctant to take on food waste because it takes more heat and time to convert into compost than yard waste. Trash also tends to be thrown into the mix, complicating composting and recycling.

“We need to start removing items from the system so we can better get at the things we can recycle,” Neil Beaver, a lobbyist for solid waste handler Recology, told a House committee in January.

Speaking at the same public hearing, Zero Waste Washington Executive Director Heather Trim noted that most consumers underestimate how finicky recycling systems can be.

“When you have a clamshell [plastic container] … and it has food waste on it, it is not recyclable,” said Trim, whose waste-reduction organization supports of the legislation. “That is contamination in the recycling stream.”

By Trim’s count, 10 local governments in Washington have already enacted prohibitions on single-use plastics. Seattle has restricted non-recyclable food-service items for more than a decade, and banned plastic straws and utensils in 2018.

Dye and others advocate using the existing tax on takeout containers to fund improvements to composting facilities, while Gregerson sees the fee as crucial to funding Washington’s movement away from disposables.

“I know the fee is always going to be controversial,” the representative said. “But we have to resource the entire system to make sure we are … supporting industry to provide products that we actually can be responsible with, so we can shift the way we live.”

Under the legislation, local governments would, with financial help from the state, begin to make single-use-item composting available. Once it is, restaurants and grocers in those communities would be prohibited from using non-recyclable, non-compostable items.

A lengthy list of items that would be affected by the plastic ban includes disposable containers, bowls, cups, bottles, meat trays, produce sacks, utensils, tea bags and sandwich wrap.

The goal is to take all single-use plastic utensils, plastic wrap and plastic packaging out of take-out dining. But there is a caveat — the Department of Ecology could waive restrictions on items for which no good alternative exists and for businesses that demonstrate a special need.

At present, there are no widely available alternatives to plastic wrap or many plastic containers used to handle hot foods, particularly hot meats. The legislation leaves it to the Department of Ecology to determine when those items would be banned in the state.

Regulators expect the new rules to be complex and controversial, and Department of Ecology leaders warned the legislation may trip up efforts launched last year by the agency at the Legislature’s direction.

“We concur that getting single-use plastics out of the environment is crucial,” said Laurie Davies, manager of the Department of Ecology’s solid waste program.

“We’re working on it,” continued Davies, speaking to the House Appropriations Committee earlier this month, “so I think this legislation might be a little premature.”

One 2019 law requires cities and counties to develop solid waste plans that reduce contamination of compostable or recyclable materials, while another directed the Department of Ecology to put together a report by October 2020 to guide efforts aimed at reducing plastic waste in Washington.

While the legislation won’t remove plastics from grocery shelves or ban plastic grocery bags, it has stirred concern among food processors and others who make extensive use of plastic packaging. Dan Coyne, a lobbyist for the processors’ trade association Food Northwest, told legislators his clients worry their industry will face regulation next.

“We look at this as simply being a tax on food that we produce,” Coyne said during a House hearing in February.

“This could be the proverbial camel’s nose into the tent,” he continued. “The next thing could be to go after the food processor as well.”

Dye said she believes market pressures may make legislation unnecessary. Consumer interest, in her view, is already pushing retailers toward compostable products.

“That’s the wonderful thing about living in our country — we’re able to do these changes through market forces,” Dye said. “We already have a great deal of momentum in the industry to provide products that please customers … in a positive way for our environment.”

Gregerson said the bill may receive a vote during a House Appropriations Committee hearing Thursday. If passed, it could then proceed to the House floor for a vote. To become law it would then have to pass the Senate and be signed by Gov. Jay Inslee.