With auto emissions of planet-warming gases rising faster in Washington than almost anywhere else on the West Coast – including even car-centric Los Angeles – Gov. Jay Inslee and conservation groups plan a major push this legislative session to aggressively reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

And while they’re still calling last year’s climate legislation victories momentous, Inslee and the greens say the 2020 session will be a chance to complete 2019’s unfinished business.

Inslee and environmental groups want cleaner fuels to power cars and trucks, and new money to help cut the risk of wildfires – which themselves have become some of the worst sources of state air pollution in certain years. Other issues likely to surface include an effort to crack down on cities that illegally dump sewage into Puget Sound, and a debate about the ecological soundness of increasing production of salmon through hatcheries to meet endangered orcas’ critical food needs.

The 2020 session lasts just 60 days, but environmentalists believe their four highest-priority bills – two of which passed either the House or Senate last year – have a good chance of making it to the governor’s desk.

One of their top priorities is a measure encouraging the production and use of cleaner transportation fuels. If it plays out as it has in California and Oregon, consumers would likely be encouraged with additional rebates to buy electric cars, and would find more charging stations around town to juice them up. Biofuels would be blended into gas and diesel to make them cleaner-burning. The price at the pump would likely rise. Builders, the oil industry and other business interests are opposed.

A bill that is expected to make its debut this session aims to reduce wildfire risks by encouraging the thinning of small trees in dense forests, and controlled burns to clear out underbrush. To fund the forest work, households would pay a $5 surcharge on every property and casualty insurance policy (which includes auto insurance)– about $15 a year for a homeowner in a two-car household, and considerably more for businesses.

Business leaders are lining up against the clean-fuels and wildfire-funding bills, saying this year’s proposals would do little to cut greenhouse gas emissions. One state lawmaker calls the clean fuel standard a ploy that would simply tax gas-fueled cars to help wealthy urbanites pay for electric vehicles.

And opponents say the bills would raise the cost of housing, increase taxes and slow the economy.

Concerns about the economy cut both ways, though. Inslee and other state officials argue that even if temperatures rise by just 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) compared to pre-Industrial levels – far below current projections for this century – Washington would see a 38% decline in snowpack. The state also would face a 23% drop in summer stream flows and a 1.4-foot rise in sea level – impacts that would have ripple effects across the economy.

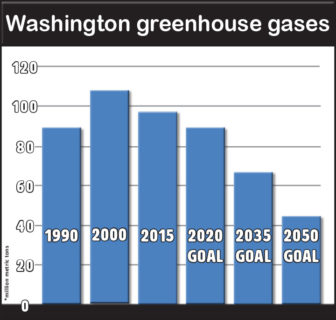

To help slow climate change, Washington’s Legislature pledged to return to 1990 levels of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020.

Twelve years ago, lawmakers pledged to reduce overall emissions of greenhouse gases to 1990 levels by the end of 2020. The state is falling well short of that goal; greenhouse gas emissions are up more than 8% percent in Washington since 1990, after hitting a peak in 2000. In every year measured, transportation has been the biggest source – even though lawmakers so far have failed to address the issue head-on.

Emissions of planet-warming gases are the downside of a booming economy that’s driving housing costs up – forcing many people to live farther away from their jobs, and commute more miles.

Even though environmentalists are coming off a victorious session in 2019 – when the Democratic-controlled Legislature passed new state laws that require all electricity to come from non-greenhouse-gas-emitting sources by 2045, and which phase out coal power by 2025 – the work needs to accelerate, they say.

“Last year’s work was momentous…but we should have passed bills like that 20 years ago,” said Vlad Gutman-Britten, Washington director for the environmental group Climate Solutions. “We need to decarbonize. We need to eliminate our reliance on fossil fuels in every part of the economy.”

The low-carbon fuel standard

Despite Seattle’s green image, a 2019 New York Times analysis showed auto emissions up 14% per capita in the Seattle metro area between 1990 and 2017 – one of the worst per-capita jumps among West Coast cities. (By comparison, Portland was down 22% per capita, San Francisco was down 9%, and even Los Angeles managed to cut its per-capita emissions by 2%.)

Oregon, California and British Columbia have tackled the issue by adopting a clean fuel standard, and Inslee wants Washington to do the same, making for a solid block of west-coast governments working toward less-polluting fuels.

Legislation to carry out that work, HB 1110, squeaked by the House last year but stalled in the Senate, where it ran into opposition in the Senate transportation committee, said its sponsor, state Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon, D-Burien. Last year’s progress means the bill, which retains the same language, will have a head start in this year’s session. Fitzgibbon, chairman of the House Environment Committee, called it the Democrats’ “one big climate priority” for this year.

If the legislation passed, companies that produce transportation fuels consumed in Washington would be required to reduce the greenhouse-gas intensity of their fuels gradually, reaching a 20 percent reduction by 2035; that would cut about 6 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year, which is akin to taking nearly 1.3 million cars off the road. (Mainly due to transportation, the state released 97.4 million metric tons in 2015. That’s equivalent to nearly 20.7 million passenger vehicles driven for one year, according to an EPA calculator. Forty-two percent of emissions came from transportation.)

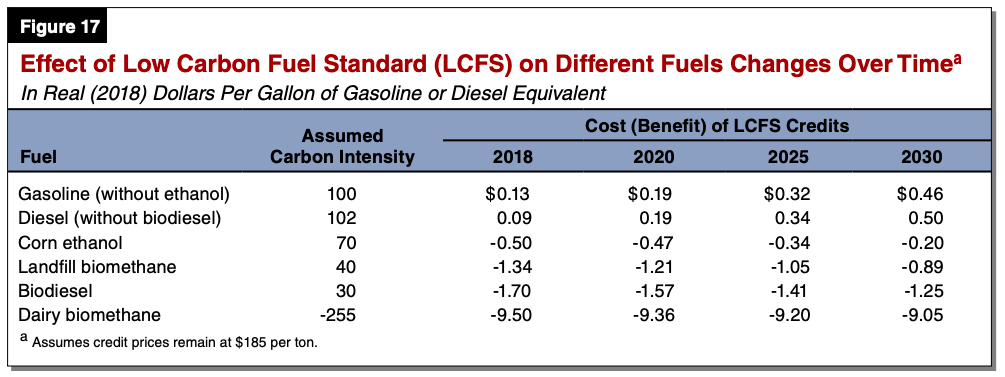

Oil companies have three ways to do it: make efficiency improvements at refineries, blend a cleaner-burning biofuel product into their fuel, or purchase credits from another producer of clean fuel, said Gutman-Britten, of Climate Solutions. The cost would be folded into the price of gasoline and other fuels.

Fitzgibbon emphasized that the bill is technology-neutral, allowing the market to find the most efficient way to reduce fuel intensity.

In Oregon, similar legislation caused gas prices to rise by less than a penny a gallon, Fitzgibbon said, and in California, the total increase has been in the low double-digits. But Fitzgibbon believes it’s almost impossible to say precisely how much the price has gone up at the pump because, he believes, the oil industry is absorbing some of the costs. “That’s one of the reasons they’re so opposed,” he said.

The industry group Western States Petroleum Association opposes the low-carbon fuel standard, calling it “an expensive and unproven experiment for Washington” that would create what the petroleum lobby describes as a “hidden gas tax.”

However, Fitzgibbon said he’s learned that BP – which runs the state’s largest petroleum refinery, at Cherry Point – is neutral on the bill.

One way fossil-fuel companies could comply is by purchasing credits from utilities that generate electricity from hydropower. The utilities, in turn, could use that money to offer rebates to customers who bought electric (EV) vehicles, bringing the price of EV cars down. Or the fossil-fuel company could buy credits from a company that installs EV charging stations, making those more widely available. The industry has chosen both of those routes in California and Oregon.

Another way to satisfy the measure: purchasing credits from a transit agency to buy electric buses. Gutman-Britten says an electric bus might generate $15,000 a year in credits, and costs less to operate, making those buses a source of ongoing revenue for transit agencies. An electric bus typically costs about $777,000 or roughly $125,000 more than a traditional bus, and operates for at least 12 years, he said.

The legislation encourages “good” biofuels – biofuels that burn more cleanly than their fossil fuel-derived counterparts. That includes biodiesel refined from canola oil, renewable natural gas harvested from manure lagoons at dairy farms, biomethane produced at landfills, and biofuel from used cooking oil. The law would create new or expanded business opportunities for companies to produce those fuels here.

SeQuential collection driver and driver supervisor Chad Peters vacuums used cooking oil into his truck outside Din Tai Fung in Tukwila. The cooking oil he is collecting into his 1,500-gallon vacuum truck will taste a second life as biodiesel, just one of the “good” biofuels that HB1110 encourages.

“We produce some biofuels in Washington, and that’s great, but all of the health benefits go to other states” like Oregon and California, which offer an incentive for companies to produce them, Gutman-Britten said. “We should be benefitting.”

Meanwhile, in a hedge-your-bets strategy, the regional Puget Sound Clean Air Agency (PSCAA) is working on a similar measure to adopt an even more aggressive low-carbon fuel standard rule. The standard would reduce the carbon intensity of fuels sold in a four-county area (King, Kitsap, Pierce and Snohomish) by 25 percent over 10 years.

Fitzgibbon thinks PSCAA’s effort improves the chances that the Legislature will want to adopt statewide measure, since lawmakers will prefer a statewide standard.

State Sen. Doug Ericksen, R-Ferndale, says both measures amount to “virtue signaling” and would have little effect on greenhouse gas emissions. He believes PSCAA doesn’t have the authority to impose such a rule, and if adopted, it would be thrown out in court.

“They’re crazy, and you can quote me on that,” Ericksen said. “They’re crazy zealots.”

Ericksen, who’s the ranking member of the Senate Environment, Energy & Technology Committee, says EVs come with environmental problems of their own, such as battery disposal. He says the clean-fuel standard would amount to taxing gas-powered cars driven by the middle class to subsidize electric vehicles driven by the wealthy.

But Gutman-Britten says new electric cars are getting cheaper, and cost about a third of a gas-powered car to fuel up and maintain. As an example, a new Nissan Leaf, which retails for $30,000, is eligible for state and federal tax incentives totaling $7,500. Used EVs can be had for about $10,000, he said. Washington has the second-largest market share of EVs in the country, after California.

Both the Association of Washington Business (AWB) and the Building Industry Association of Washington are urging legislators and PSCAA to reject the measures.

BIAW spokeswoman Jennifer Spall said business leaders are alarmed by a 2019 PSCAA analysis on the standard’s impact which found that in the 4-county area, the fuel standard could cost consumers and employers up to $2 billion for new vehicles, fuel supplies and infrastructure.

Spall said increased transportation costs would hit builders and suppliers, who use trucks to move items around during construction. BIAW won’t support proposals if they could increase housing costs at a time when the state is in the midst of a housing affordability crisis. “The Legislature needs to start controlling the costs of housing, not further add to them,” Spall said in an email.

In California, where the standard went into effect in 2010, one study showed the rule hasn’t done much to decrease greenhouse gas emissions and will cause prices at the pump to rise by about 19 cents in 2020, said Mike Ennis, a government affairs director for AWB, the state’s oldest and largest business association. He says PSCAA’s analysis suggested prices here could rise as much as 57 cents per gallon by 2030. “That raised a lot of concerns for the business community,” he said.

A study in California shows how prices at the pump will rise as a result of the new fuel standard. (Photo: California Legislative Analyst’s Office)

Ennis was critical of the PSCAA’s report for not showing the measure’s cumulative effects on the economy, or adjusting for inflation. He says it would reduce the gross regional product across Washington state by $1.4 billion between the time of its adoption and 2030.

AWB prefers an incentive-based approach, rather than a mandate. “We think creating incentives for private companies to accelerate the movement toward cleaner fuels is much more effective,” Ennis said, and noted that the auto industry is continuing to produce cleaner-running cars.

“I think the technology is working – I think it will solve this issue,” Ennis said. “It’s just a matter of time.”

The Washington State Medical Association and Washington Academy of Family Physicians have both endorsed the clean fuel legislation, saying it benefits communities most impacted by air pollution and climate change. Low-income residents are among the hardest-hit by exhaust from cars and trucks, since many affordable homes are located next to freeways.

But business lobbyist Ennis points out that the Clean Air Agency’s study shows that the standard would only slightly decrease air pollution as measured by fine particulate matter, and that it has decreased California’s greenhouse gas emissions by an insignificant amount. “We don’t think the cost justifies the benefit,” Ennis said.

Setting new greenhouse gas limits

Washington is likely to fall well short of the greenhouse gas emission cuts required by year’s end, as dictated by legislation passed in 2008. Now, Inslee has requested new legislation that would double down on emission cuts, saying even bolder action is needed.

Instead of the current goal of reducing human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases 50% below 1990 levels by mid-century, new legislation would be expected to, in effect, achieve net zero emissions, with more-aggressive interim targets as well.

The legislation (HB 2311) “sets the stage for all the work we need to do together in the future,” said Mo McBroom, director of government relations for the Washington chapter of the Nature Conservancy.

A part of the decrease would come from so-called natural climate solutions – recognizing the role forests, agricultural lands and wetlands play in sequestering carbon in the soil and in living plants. The bill will help set the policy needed to pass future legislation encouraging those practices, said Rebecca Ponzio, the climate and fossil fuel program director for Washington Environmental Council and Washington Conservation Voters.

That’s likely to include new programs to pay landowners incentives for growing trees longer before harvest, and for agricultural practices that sequester soil carbon, McBroom said.

Improving forest health

Thinning young trees in dense forests and burning underbrush: That’s the prescription for more fire-resistant forests, says the state Department of Natural Resources in its 20-year forest health plan. Fitzgibbon is sponsoring a bill, endorsed by environmental groups, that would help raise money to pursue that work.

The bill would put a $5 surcharge on every property and casualty insurance policy issued in Washington. (Casualty insurance includes auto insurance.) It’s expected to cost the average homeowner with two cars $15 a year; businesses, which often hold a number of different policies, would pay more. It would generate about $60 million a year for forest maintenance.

That money would be used to train people how to safely set prescribed burns – a type of controlled burn that clears underbrush in forests and makes them more resistant to wildfires – and to pay for cutting and clearing away small trees, including field work by foresters to identify those trees. That thinning work reduces the fire risk; state money is needed because those young trees have little market value, Fitzgibbon said.

Firefighter Steven Thime hops onto a tree stump to survey the progress of a prescribed burn in Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest near Liberty, Wash. (Photo by Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest)

Passing the plan in its current form will be tough, and the Environmental Priorities Coalition, a legislative alliance of more than 20 green groups, did not make this one of its top four priorities.

Ericksen, the Republican legislator, says a tax increase to do this work is “absolutely unnecessary.” He says the state would be better served by loosening regulations that constrain private landowners from managing their forest lands.

Both controlled burns and thinning may rub some people the wrong way. Controlled burns cause air pollution during the short periods in which they take place, and there’s a risk they can get out of control. And some environmental groups fear timber companies will take advantage of thinning to remove more trees, or bigger trees, than necessary.

McBroom acknowledged there’s been mistrust between environmentalists and timber companies in the past, but says both sides understand each other better now, and agree on what works. “There is a lot of agreement about the need to actively manage forests, and leave certain parts of the forest alone,” she said. “We can do these things while putting people to work.”

The new money would also purchase more firefighting equipment such as helicopters, and pay for fire prevention activities.

The $5 insurance surcharge is opposed by the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, an industry group, because its benefits “accrue mostly to people who live in wildfire prone areas and those who suffer from smoke related ailments,” said Mark Sektnan, vice president of state government relations for APCIA, in an email. “Reducing these ailments, while a benefit to society, is not related to driving a car or owning a home or business in other parts of the state.”

Boosting salmon populations

The state has long had a goal of no net loss of habitat for salmon, yet each year in the Puget Sound area, 800 acres of forest are lost to development, and about 2,000 acres of ecologically important land are lost statewide, said Mindy Roberts, the Puget Sound director for the Washington Environmental Council and Washington Conservation Voters, who served on the governor’s Orca Recovery Task Force. That’s 4.34 square miles lost each year, akin to the land size of North Bend. Chinook salmon, the orcas’ preferred food, have declined to a fraction of their historic abundance.

Chinook salmon, killer whales’ main food source, are key to heading off the extinction of Puget Sound’s beloved orcas.

The bill called “Healthy Habitat, Healthy Orcas” would create a policy of a net ecological gain of habitat for salmon, with the aim of improving fish stocks to help the endangered southern resident orcas, now down to 73 animals.

The bill is still being drafted, but one example of a policy that would improve habitat is cleaning up toxic waste sites to improve water quality, Roberts said. Scientists say that one of the major threats to orcas – especially the three endangered family groups that frequent Puget Sound – is toxic chemicals that interfere with the killer whales’ reproductive, immune and nervous systems and can cause cancer.

“We need to leave this place better than when we found it,” Roberts said.

Getting rid of thin plastic bags

Thin plastic bags, sometimes called t-shirt bags, would have been banned statewide under a bill that passed in the Senate last year, but failed to pass the House and is coming back this year. The bags already are illegal in many Washington cities because they snarl recycling machinery and end up in waterways. Scientists say they are increasingly found in the stomachs of whales that are dying around the world. One example was recorded in 2010 in West Seattle.

This bill wouldn’t do away with plastic bags entirely; merchants could replace them with either thicker plastic bags – which tend to get reused – or paper bags. But the real goal is to encourage people to bring their own when they go shopping, said Heather Trim, executive director for Zero Waste Washington.

Consumers would be charged 8 cents for every paper or thick plastic bag they purchased.

Washington role as a national leader

Environmentalists say Washington has a national role to play, helping to lead the country toward progressive climate solutions. The growing youth movement for climate solutions and the attention now trained on climate change makes it a pivotal year. “We have no time to lose,” McBroom said. “We have to seize this opportunity now, and we have a chance in Washington to lead.”

Lobbyist Clifford Traisman, who represents a number of environmental groups, is upbeat about making this the second year in a row for environmental progress. Last year, in addition to committing to clean energy and the end of coal, lawmakers passed bills to increase energy efficiency in large office buildings, cut the use of certain types of refrigerants which contribute significantly to climate change, and provide additional incentives for electric cars and charging stations.

“We look at the agenda, we look at the political landscape of the Legislature and the low cost of these proposals, and we expect all four to pass,” Traisman said.

Levi Pulkkinen contributed to this report.

This story has been corrected. It originally say the Oregon legislation passed last year. It passed in 2015 and went into effect in 2016.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at http://www.invw.org/newsletters/.