Youths entrusted to Washington’s foster-care system have endured “abusive” practices in a jail-like Iowa group home that inappropriately used painful physical restraints on children, according to a new report by a government-designated watchdog group.

The report, released today by the nonprofit Disability Rights Washington, documents numerous instances in which youths between the ages of 14 and 16 were held down by three or more workers. One child’s glasses were broken when staffers pushed the youth to the floor, and another was restrained for 45 minutes.

Washington social workers knew of the practices — some of which would not be allowed under Washington regulations — but failed to “ensure the rights and safety” of the teens, the report says. It focuses on the cases of three teens who were among about 20 Washington youths confined at the for-profit Clarinda Academy, which also houses juvenile delinquents, and a sister Iowa facility, Woodward Academy.

“It hurt, I had bruises,” Kathie, 16, said of the restraint holds she says Clarinda staffers used on her a few times a week throughout her recent six-month stay at the facility. She spoke to InvestigateWest from a phone in her new group home in South Carolina and on the condition that this story use only her first name.

The report points out that the state places young people in the custody of out-of-state group homes like Clarinda “without consent or due process,” circumventing protections against involuntary commitment.

Youths’ case files obtained by Disability Rights show that Clarinda workers “use physical restraint for questionable reasons at best, and in some cases without justification,” the report says.

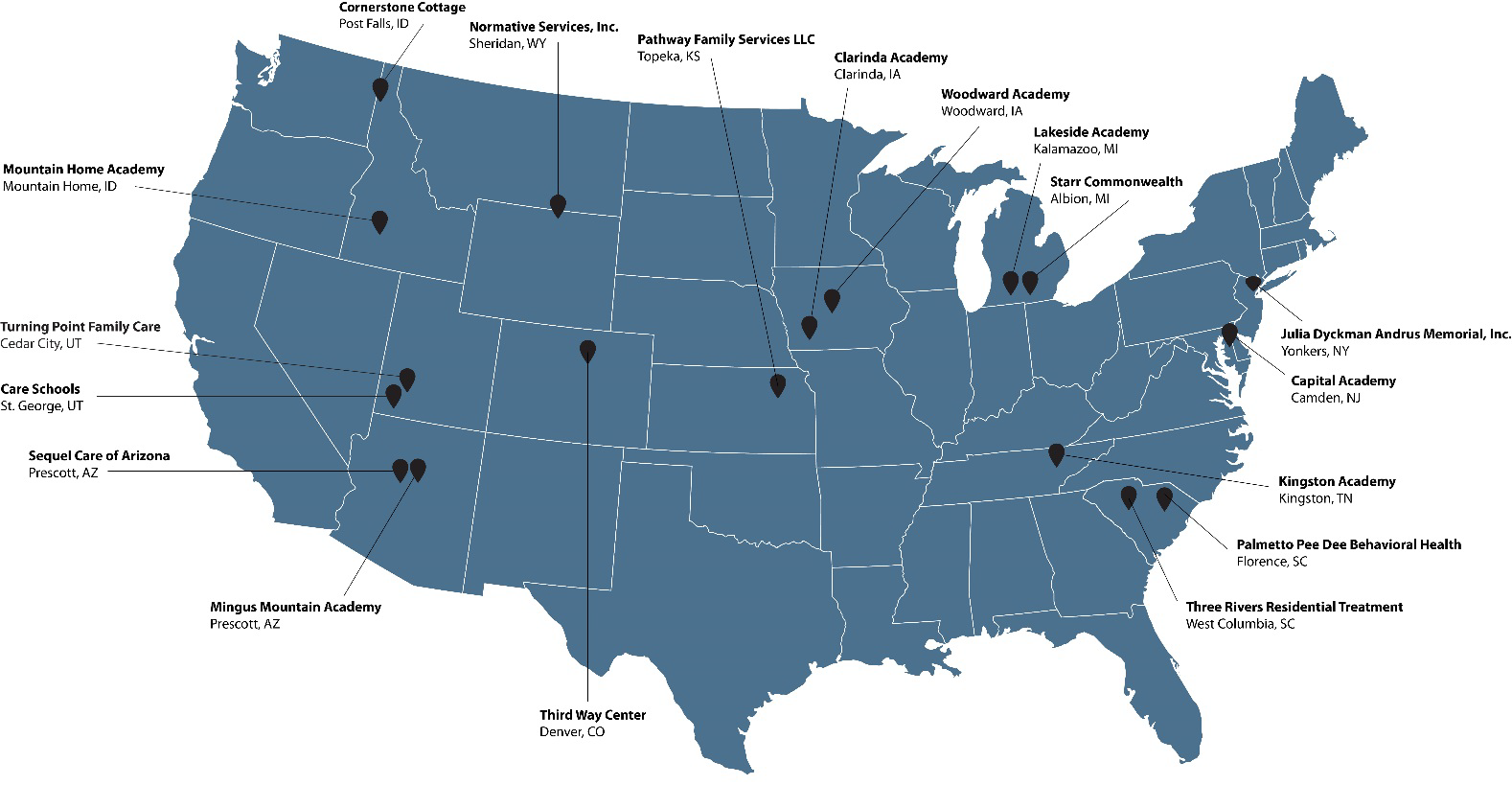

Many of the youths in question would not have to be sent out of state if not for Washington’s long-festering and desperate shortage of foster homes and group homes for youth with behavioral and mental health challenges. Washington increasingly relies on facilities spread across a dozen states to house neglected and abused children removed from their parents.

Between 80 and 100 Washington children are now in out-of-state facilities. As those numbers have risen in recent years, attorneys and advocates for foster youth have sounded the alarm about the state’s ability to adequately monitor children in distant states, as InvestigateWest reported last month.

Map shows locations of group homes where foster youths have been sent by Washington State Department Children, Youth and Families, according to new report.

The investigation released today by Disability Rights Washington, a group appointed under federal law to monitor the care of people with disabilities and mental illness, suggests those concerns are well-founded.

In interviews with a dozen youths at Clarinda and Woodward in early 2018, the organization heard consistent allegations of verbal and physical abuse. That prompted Disability Rights to launch an in-depth examination of three youths’ case files and internal Clarinda documents. Those records, it concludes, “demonstrate that Washington and Clarinda Academy are both failing to protect against the use of restraints for coercion and punishment for not following expectations.”

Clarinda Academy management and a lawyer for the company did not respond to multiple phone calls and emails requesting comment.

Washington sends dozens of foster youths to some of the other 29 similar group homes owned by Clarinda’s parent company, Sequel Youth and Family Services. As of 2017, about three-quarters of Washington youths in out-of-state group homes were in Sequel facilities, and the company had plans to begin operating in Washington, according to Disability Rights.

State officials said they took the report seriously and, based on a draft sent to the state in August, stopped sending kids to Clarinda and created plans for all children still there to find permanent homes or return to Washington by the end of next January. They also dispatched state workers to check on all foster children in out-of-state facilities.

For young people like Kathie with a history of childhood trauma, being physically restrained can cause further harm and worsening behavior, studies show. Yet treatment plans at Clarinda weren’t designed to effectively address youths’ traumatic history, according to Gauri Goel, a psychologist who interviewed the youths and reviewed their records as part of the Disability Rights inquiry. Instead, she wrote, “the treatment they are receiving is likely to be ineffective and potentially counterproductive.”

A 2014 investigation of Clarinda by Disability Rights Iowa also found that the facility uses a “one-size-fits-all” approach to treatment and schooling, the Des Moines Register reported.

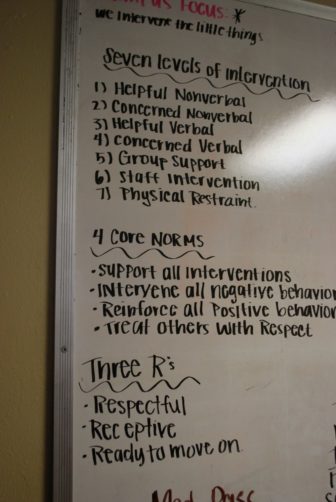

Clarinda policy, as well as Iowa and Washington regulations, say youths should be physically restrained only when they present an imminent danger to themselves or others. But at Clarinda, residents who are being reprimanded are expected to stand completely still, and the report documents instances where the teens were restrained merely for moving an arm or hand.

“Say that I was going to wipe my tears or cover my face because I’m crying,” Kathie told InvestigateWest. “Any sudden movements, I would end up getting restrained.”

One teen was restrained for not obeying an order to stop scratching his legs, another for disrupting other residents in a dining area and refusing to leave.

Confidential Exhibit A from new report is an excerpt from a youth’s letter pleading with Washington State to take him and others “back home.”

Youths showed Disability Rights how workers would “pull their elbows behind their backs and then force them to the ground by putting pressure on the backs of their knees,” the report says. Unlike Washington’s more stringent regulations around the use of restraints, Iowa’s do not prohibit pressure on joints, the chest or vital organs.

Originally set up as a facility for “delinquent” young men, Clarinda Academy now houses up to 266 young people ages 12 to 18. Its “typical student” is a juvenile offender, according to the parent company website.

That helps explain why Clarinda is run “like a correctional institution,” according to Disability Rights, even though Washington youths are sent there through the foster care system, not because they have committed a crime.

Clarinda sits across the street from a medium-security prison.

Clarinda Academy houses up to 266 young people and is run “like a correctional institution,” according to Disability Rights, even though Washington kids are sent there through the foster care system, not for committing a crime. Clarinda sits across the street from a medium-security prison.

The facility is tightly controlled. Boys and girls are strictly segregated, and in one case a youth was restrained for refusing to leave a hallway where children of the opposite gender were going to pass, the report says.

The youths attend school onsite, and they rarely leave. If they attempt to leave without permission, staffers restrain them and bring them back.

“For all practical purposes, they don’t have a choice to say, ‘I don’t think I need this level of treatment’ or ‘This program is not helping me.’ They don’t have that power,” said Disability Rights attorney Susan Kas, who made two trips to meet with youths at Clarinda.

In Washington, young people age 13 and older have the right to leave an inpatient mental health or substance abuse treatment facility they entered voluntarily. State laws also protect them from continued involuntary treatment without a hearing.

“Children in foster care do not lose these rights by virtue of having been removed from the care of their parents,” Lisa Kelly, a law professor at the University of Washington, wrote in an email. “They have the same rights as any other child in this state, and these rights are being ignored when they are essentially involuntarily committed to secure facilities that not only sit next to prisons but also possess many of the same restraints on their personal freedoms as prisons.”

Beyond the potentially harmful treatment practices at places like Clarinda, being cut off from family and other important adults in their lives is one of the most damaging consequences of out-of-state placements, advocates say.

Isolation is a key danger. Phone calls home are limited to 10 to 20 minutes per week. Washington provides financial help if family members want to visit foster youths sent out of state. But for children who are not connected to kin, the system rarely offers similar aid to family friends or others who might agree to take in the young person. Kathie said she didn’t receive a single in-person visit during her six months at Clarinda. As a result, connections with adults who might adopt or foster children upon their release tend to wither. “That was very devastating to the young people,” Kas said.

To help kids get back into a family setting, rather than another institution, Kas said, it’s essential to support them in developing and maintaining those relationships.

“There’s a tendency to say, we don’t have enough group home beds here in Washington, so let’s get more group home beds, and then we can just shift everybody back to Washington,” Kas said. But discharging them to a family home, and hopefully a permanent one, “should be the goal of our system if we are going to do right by these kids.”

Washington social workers also did not visit their charges in Clarinda, relying instead on reports from Iowa social workers. Even when they receive written reports from Iowa and Clarinda case workers about use of restraints, “Washington social workers do not follow up on allegations of abusive restraints,” Disability Rights found.

The Department of Children, Youth and Families said in a press release embargoed for release today that it will begin requiring case workers to call out-of-state youths monthly and visit them quarterly.

The department wrote that it “agrees with Disability Rights Washington’s main premise that children in out-of-home care are in general better off as close to home as possible, and that we should place all children in in-state facilities where possible.” However, it continued, “DCYF can’t cavalierly ‘bring them home’ without a plan to address each child’s individual needs and a placement option that is better than the placement they are in today.”

Department Secretary Ross Hunter called in his recent budget proposal for bringing all out-of-state Washington foster youth back within two years. Part of his plan involves shoring up capacity in Washington group homes, which have cut beds in recent years due in part to low reimbursement rates from the state.

The department did not respond to a query from InvestigateWest about how much it pays Clarinda, but similar facilities in Washington are eligible to receive more than $12,000 per month. Sequel’s projected 2017 revenue for all of its residential treatment centers was $161 million, or more than $69,000 per bed, according to an investor presentation. A private equity firm acquired a majority stake in Sequel last year, citing “tremendous continued growth opportunities.”

Over the past few months, the state has removed the three youths who were the focus of the Disability Rights Washington report from Clarinda, but two remain in other group homes.

Kathie, who has been in foster care since age 13, said her new group home is “just as terrible” as Clarinda, and that staffers there still physically restrain her.

Yet, Kathie said, she’s doing better. She hasn’t harmed herself in almost two months. She dreams of returning to live with her best friend in Washington and to her school choir. Someday, maybe she can sing on “America’s Got Talent,” she prays.

In the meantime, she hopes the state will give kids like her another chance and bring them home. Keeping them out of state is “making us kids more and more stressed,” she said. “It doesn’t help anything at all.”

This story originally said Kathie is in a group home in North Carolina. It has been corrected to make it clear the home is in South Carolina.

Do you know of other problems with out-of-state placement of foster youth? Please contact reporter Allegra Abramo at aabramo@invw.org.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at https://www.invw.org/newsletters/.