A single mother with three of her five children still teenagers living at home, 50-year-old Denita Simmons didn’t plan on adding two babies to the mix. But her godsons needed her. The boys’ mom, a friend of the family, left the boys in Simmons’s care for longer and longer periods as she struggled with drugs. As days stretched into months, Simmons found herself the de facto mother to an infant and a toddler, even as she battled her own depression, anxiety and later breast cancer.

“Some people take stray cats home. These are people that were abandoned — two little toddlers that no one wanted and that needed somebody,” said Simmons, now 61, of her decision a dozen years ago. “It struck a chord in my heart because I grew up without a dad, and I know what it feels like to not be wanted.”

Simmons is one of the growing ranks of grandparents, aunts, uncles and close family friends who have stepped in to raise children who have lost their parents to incarceration, mental illness and, increasingly, to opiates and other drugs.

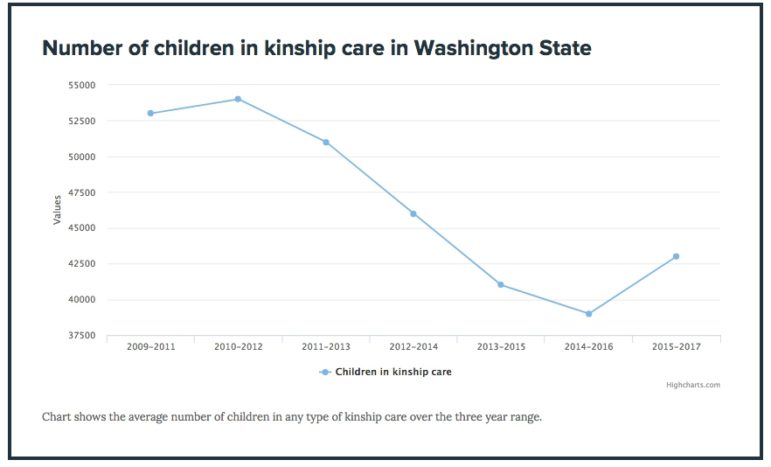

These “kinship caregivers,” as they are called, today care for an estimated 43,000 Washington children outside of the state’s formal child-welfare system. That number is lower than at the height of the Great Recession, but has crept up in recent years.

Without these family members, many of the children would likely wind up in Washington’s foster care system, which is already in a state of crisis. With just over 9,100 foster children and a shortage of licensed foster homes, state social workers have resorted to housing hundreds of children in hotels and state offices. If these kinship caregivers went away tomorrow, it would cost taxpayers untold millions and would almost certainly push a teetering system into collapse.

Yet the state does relatively little for these grandparents and other caregivers, who tend to be older, poorer and in worse health than foster parents. About one-quarter have a disability. Only about one in five gets any cash assistance from the state, and those payments fall far below the typical monthly support for foster parents.

As a result, overall state spending on programs and financial assistance for kinship caregivers amounts to roughly 10 percent of the total budget for foster care and adoption.

Advocates say that relative caregivers need more help, including financial assistance, mentoring, state-paid time off known as “respite care,” and legal services.

“Let’s give them some support,” said Lynn Urvina of Olympia-based Family Education and Support Services, one of a handful of “kinship navigators” who help connect substitute parents with services, and who is raising her own granddaughter. “Because if all of these children were to show up in the foster care system tomorrow, the state wouldn’t know what to do.”

Keeping kids out of foster care not only saves Washington taxpayers tens of millions of dollars annually, but research indicates that living with relatives is often better for children. Compared to children placed with strangers in foster care, those in kinship care have a lower risk of behavioral problems and are less likely to move frequently between homes. That stability is important, because the dozens of moves some children endure in foster care can propel them on a downward spiral of worsening behavior, school failure and entanglement with law enforcement.

Financial support is one of caregivers’ biggest needs, Urvina and other kinship experts say.

Kin caregivers can apply for payments that amount to $363 per month for the first child and less for each additional child. A grandparents caring for three children would get a total of $569 per month in welfare payment for low-income families under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or TANF. Reimbursements for licensed foster parents start at $562 for each child, and can go up to $1,500 or more per month depending on a child’s age and needs.

One piece of good news for caregivers in Washington came last year when state lawmakers repealed rules that limited payments based on income. This means that, as of this summer, all caregivers can receive the benefit, regardless of their income. But many caregivers don’t apply for assistance, advocates say. Doing so triggers the state to seek reimbursement from the birth parents, Urvina explains. Many caregivers fear that could spur family conflict. Others simply don’t want to inflict more hardship on the struggling parents.

For Simmons, who retired early from her work in sales due to depression and other mental health challenges, just providing the necessities for two growing boys is a constant struggle. Small luxuries like a trip to the movies are out of reach, she says. A few years ago her electricity was shut off in the middle of winter, until a social service agency helped resolve the overdue bills.

“Every month I’m struggling to figure out how we are going to make it to the next watering hole,” Simmons said.

Most lawmakers don’t understand the sacrifices caregivers make, says kinship navigator Urvina. That makes it difficult to persuade state legislators to pony up to help them.

“They will say things to me like, ‘Well, that’s her grandson, of course she’s going to take care of them. Why should we have to provide financial support?’

“My answer,” Urvina said, “is usually something like, ‘Have you priced a size-14 pair of tennis shoes lately? And why should grandma have to not fill her heart medication so that she can pay for tennis shoes? It doesn’t increase her Social Security just because she takes in a grandchild.’”

The state spends about $31 million a year on programs and financial support for kin caregivers, compared to more than $315 million for foster care and adoption. About $1 million of that pays for one-time emergency grants to help with expenses like rent, utilities, cribs and car seats — an amount that hasn’t changed since 2006, according to the Department of Social and Health Services. An additional $1 million supports 7.5 kinship navigators, plus recently added navigators for eight Indian tribes, who administer the emergency grants and connect caregivers with legal help and other services.

The state will soon have the opportunity to expand its kinship navigator program by tapping into federal matching funds provided under the Families First Prevention Services Act. Passed in February, the act aims to help kids remain with their families by allowing states to spend federal foster care dollars on drug treatment, mental health care and other services for parents at risk of losing their children. Meanwhile, King County officials this summer approved hiring an additional navigator funded by the Best Start for Kids tax levy.

Caregivers’ health problems also can strain their ability to keep the kids in their care. But unlike licensed foster parents, they are not eligible for free services that provide caregivers respite from the demands of child-rearing. When a health crisis strikes, caregivers are on their own.

Alice Doyel learned how hard it is for caregivers to get help when her seizures and immune disorder suddenly worsened in 2016. The 73-year-old south Seattle resident barely had the strength to take care of herself, let alone the energetic preteen grandson in her custody.

As Doyel’s health spiraled downward, so did the behavior of her grandson, TJ, whose early-life neglect and exposure to domestic violence predisposed him to angry outbursts, she said. Desperate for rest, she begged state social workers to find someone who could supervise her grandson for a few hours or days. Such assistance, she was eventually told, would cost her $1,500 for a weekend, and more if TJ exhibited behavioral problems.

“My response was, ‘I think we’d rather stay at the Fairmont Hotel for the weekend,’” Doyel said, referring to the luxury hotel in downtown Seattle.

Eventually TJ’s school helped find him an afterschool program, and Doyel’s health slowly stabilized. As she got better, so did TJ. Now 12, he is no longer the angry, sometimes-violent child she removed from neglectful circumstances six years ago.

It has taken most of that time for TJ to attach emotionally to Doyel, she says. Now his caring and concern for Doyel’s health shine through. “He’s so watchful,” she said. “Even if he’s riding his bike and I’m walking, he always waits to see if I’m OK.”

Foster care, Doyel says, would have been a disaster for a child like TJ. “He would have been one of the kids who would have been from home to home to home,” she said. “He would have been in the juvenile justice system.”

Similarly, Simmons believes that her godsons, now ages 11 and 13, would have bounced around in foster care after being abandoned by parents with a history of substance abuse and arrests, according to her petition for custody. The older boy, Emari’ay, didn’t speak until he was four years old, Simmons said, and he had to go through years of physical therapy to improve his motor skills. Xavier was expelled from kindergarten due to emotional outbursts. Both still struggle with developmental delays and the trauma of being separated from their parents.

For Simmons and Doyel, finding affordable mental health care for their boys, shuttling them to medical appointments and negotiating with schools has been an exhausting, and often lonely, slog. Unlike foster parents, they don’t have a state caseworker to help them find assistance and navigate services. But both women understood that giving up was not an option.

Today, Simmons’s godsons call her “mom.” Emari’ay dreams of being a pilot and is spending the summer helping teach other kids to play tennis. Xavier immerses himself in constructing complex worlds out of Legos, and says he wants to become an architect, or maybe a fireman.

“We have formed a strong bond and love and concern for each other I that never thought would be there,” Simmons said, “because I thought they were too emotionally damaged.”

In addition to providing critical stability, living with relatives or close family friends can alleviate some of the trauma associated with losing a parent, says Judge Frank Cuthbertson, a Pierce County Superior Court judge who presided for two years over cases in which children had been removed by Child Protective Services. He now oversees the county’s Mental Health Court, where many of the parents also are working to get their kids back.

In those roles, Cuthbertson has seen how kinship arrangements often create the best conditions for children to return to their parents.

The power of those family bonds was on display recently in Cuthbertson’s court room. After a long battle with methamphetamine and alcohol, combined with mental health issues, a mother graduated from the Mental Health Court’s 18-month program. Not only had she gotten her life back, she told Cuthbertson, but she also got another chance to be a mother to her preteen son. Throughout her treatment, the woman’s own mom had cared for her grandson, showing up often in court to support her daughter.

“If we didn’t have her mom willing to be a kinship caregiver while she went in and out of treatment, jail and everything else,” Cuthbertson said, that reunification “wouldn’t have happened.”

Family members, Cuthbertson said, can “help rebuild the bonding between the parent and the child. That’s another reason why I think kinship caregiving is really important and something we don’t think about enough.”