Nearly two decades ago, during a high school football game in Waldport, a 17-year-old quarterback named Max Conradt lined up under center and began a snap count.

Ready. He’s nursing a concussion from the previous game.

Set. He hadn’t slept the night before; headaches kept him awake again.

Hike. Conradt’s lineman misses a block and a defensive end for Taft High School hits Conradt from the blind side. Conradt’s uniform is turning brown from rubbing against the ground so often. He picks himself up and wanders into the opposing team’s huddle, confused, punch drunk from the hit.

Nobody pulls him out of the game. Instead a teammate leads Conradt by the elbow into the right huddle.

On any other night the kids playing defense for Taft High School might have received some postgame high-fives for the way they were playing, for the kind of hurt they were imposing. But not tonight. After tonight their coach will delete his game film; he doesn’t want them reliving the next moment. The huddle breaks out and Conradt lines up under center.

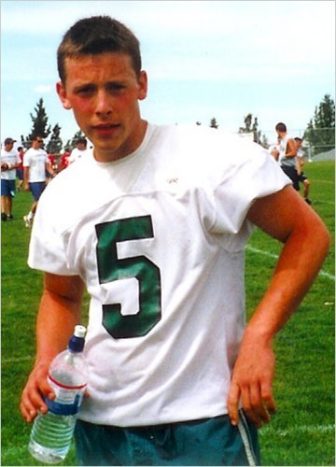

Before his brain injury, Max Conradt was an honor student at Waldport High School, with plans to play football and study journalism at Cornell University.

Ready. Conradt’s brain has been sending distress signals all week, like flares from a sinking ship, in the form of headaches, sensitivity to light, and extreme discomfort during exercise. But these warnings went misinterpreted — in the culture of a 2001 locker room — as weakness of character, the kind of phantom injury other people used as an excuse to miss practice. So Conradt pushed through. He took aspirin and showed up for game day.

Set. Conradt won’t remember the snap. He will take a knee as the clock runs out on the first half and then, while walking to the sidelines, collapse. He will wake up in the hospital, several weeks later, with the mental capacity of a 9-year-old.

For Conradt’s father, Ralph Conradt, filming his son’s game from the sidelines, this is the moment before his family disintegrates. Down on the field, Conradt is still is Ivy League-bound, with aspirations of becoming a sportswriter, with one last moment under the Friday night lights to enjoy the potential of his youth.

Later, his own father will describe this as the night his son died, replaced by someone else. A law with his namesake will be passed to protect future athletes from the kind of tragedy that’s about to unfold. In a way, Max Conradt is about to take one for the team.

Hike.

The catalyst

Conradt’s story might have ended there if not for his dad, according to David Kracke, a personal injury lawyer who, at the time of Conradt’s injury, was on the board of the Oregon Brain Injury Alliance.

“The legislative process tends to require a catalyst, a spark,” Kracke said. “And in this case, Ralph Conradt was that spark. Ralph didn’t let it go. He kept saying that something must be done. This can’t happen to another kid.”

Today Max Conradt lives with his wife and daughter in Salem, supported by funds from a lawsuit settlement, but in 2009, eight years after his injury, Oregon became the second state in the nation, following Washington, to pass legislation protecting student athletes from the impact of concussions.

“Max’s law,” as it is commonly known, requires coaches to pull an athlete from play following a concussion and restrict them from training or play until a medical release has been obtained by a health professional. Even then, the athlete must show no symptoms and can return no sooner than the day after receiving the suspected concussion.

Today, most states have similar laws. But the Pacific Northwest led the nation in adopting concussion management, according to Kracke, who helped to co-author Max’s Law.

“2009 or 2010 was when the NFL came back with that horrific determination that football doesn’t cause concussions and at the same time Oregon and Washington were addressing this on a state level and on a youth sports level,” Kracke said. “It was a weird convergence of circumstance and geographic location and a sense of urgency. And that was something that I think drove us all.”

Max Conradt, who suffered back-to-back concussions in high school, was on hand when Gov. Ted Kulongoski signed “Max’s Law” in 2009. The pioneering legislation was aimed at ensuring that student with brain injuries do not return to sports activities prematurely.

Max’s Law does not prevent the first concussion. Doing that might require changes to the games themselves. Things like eliminating the kickoff in football or banning headers in soccer. Collisions in a sport like football are inherent to the game. And in some ways Oregon hasn’t matched the progress seen elsewhere in making sports, particularly football, safer.

As an example, Oregon high school football teams are permitted to have three days of full contact tackling practice per week. By contrast, the Pac-12 and Ivy League limit college full-contact practices to twice a week. And the NFL only allows one day of full contact per week.

But Oregon’s law isn’t designed for that. It’s aimed at reducing the overall number of concussions and their impact by preventing players with post-concussion syndrome like Max Condradt from being on the field

“This is about education” of coaches, staff and players, Kracke said.

Medical OK required

Max’s law meets the three criteria recommended as best practice for concussion legislation per the National Conference of State Legislators. It mandates training for coaches, requires the removal of an athlete from play following a concussion, and requires a student to obtain a release from a health care professional in order to return.

Under the law, public school sports coaches are responsible for taking an annual training course that teaches them to spot and respond to concussion symptoms. The National Federation of State High School Associations offers a free online course to obtain certification. The course, endorsed by the Oregon Student Activities Association, details how dizziness, vomiting, ringing in the ears, and headaches are all possible symptoms of a concussion. The training is meant to emphasize that symptoms are varied and sometimes subtle; only about 10 percent of concussions result in being “knocked out.”

The NFSH course requires coaches to watch a series of short videos that can’t be skipped, and pass a multiple-choice test in order to be certified. It is about as rigorous as what bartenders go through to obtain an Oregon Liquor Control Commission card. Though unlike the OLCC, the concussion certification test can be failed and retaken with no penalties or limits on attempts.

The law also imposes a concussion protocol for injured players returning to the field. By law, coaches are stripped of their ability to evaluate whether an athlete is able to return after a concussion. Instead, that decision must go through a health professional.

The law specifies that an athlete can return no sooner than at least a day after receiving the concussion. In order to return to play, a student must show no symptoms of a concussion and retain a signed release from a medical professional.

In practice, the typical student is then gradually introduced to physical activity beginning with light aerobic exercise. From there, if the student continues to be symptom free, he or she can return to full participation.

The law only applies to public elementary, junior high and high schools, but a sister law called “Jenna’s Law” extends a similar protection to private schools and club sports. Passed in 2013, the law is named after Jenna Sneva, a championship skier from Sisters, whose racing career ended due to a history of concussions.