Over the past six months, Lee van der Voo has made 235 requests for concussion records — or rather, the same request 235 times.

Van der Voo is managing director of InvestigateWest and the designated data wrangler for Rattled: Oregon’s Concussion Discussion, a statewide investigation her nonprofit is conducting with Pamplin Media Group.

Oregon law requires a medical professional to sign off before an athlete competing for a school-based team can return to practice or competition after suffering a concussion. That, in turn, generates a public document. Van der Voo has contacted every public high school in the state and requested return-to-play forms omitting the athletes names and dates of birth generated in the past two years.

Oregon has one state law to govern how local jurisdictions handle public records. But the responses to the same request — as any journalist can tell you — are wide and varied, depending on the agency.

Van der Voo has received responses ranging from neatly ordered documents arriving the next day, to long, drawn-out battles, to complete silence. (Complete list here.)

Return-to-play forms have been used in Oregon since 2009 to ensure that athletes with head injuries didn’t return to the field without medical supervision. Experts say serious or even simply repetitive head injuries can have serious long-term effects, especially for children. And those who return to play too soon following injury are at risk for Second Impact Syndrome, a serious brain injury that can result in lifelong brain damage, or even death.

The requests for these public records have specifically asked for redactions of personal information, in compliance with the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

“They’re public records because they’re compiled by a public agency about a public health issue,” van der Voo said. “We just want to know that schools are tracking the issue in compliance with the law, and whether they have information that, if properly analyzed, would benefit everybody to know.”

A model agency

Responses varied widely, van der Voo said, from the North Clackamas School District, which worked closely with her to produce records from four high schools, to the 135 school districts that had to be contacted repeatedly to even acknowledge they’d received the requests.

Corvallis School District officials initially refused to consider a public records request via email, saying school policy called for a letter mailed through the U.S. Postal Service. Dayville School in Grant County required the request first be submitted to and vetted by a lawyer. One athletic director said he would provide records only if the other athletic directors in his district provided them.

Van der Voo said the best agency to work with during this project was Parkrose School District — a small district in Northeast Portland.

“I made this request at Parkrose School District and the principal called me and said: ‘We actually have a spreadsheet; would you like that?’” van der Voo said. Conversations, she believes, are key to agencies efficiently providing requesters what they want.

Parkrose High School Principal Molly Ouche said it is best practice to store good records and analyze them to find what can be learned. Ouche said she was happy to be able to provide the records quickly.

“As long as it doesn’t compromise student privacy rights, I think the more schools are transparent, the more the greater community is able to support the work we are doing and be aware of our strengths and the areas where we need growth,” she said.

Aside from several small districts that have simply not responded, van der Voo has found that Oregon’s smaller school districts have been the most responsive overall.

“I had a lot of districts, small districts, just kick me records the next day,” she said. Larger school districts, she acknowledges, have more records to pull together over multiple schools, which can delay responses.

Understanding this, she started with the state’s largest district first, back in September, and still found them the most frustrating to work with.

PPS delays for months

The Gresham-Barlow School District initially redacted nearly all the information in the requested concussion documents. The Multnomah County District Attorney told the district to comply with the request, which it did.

Portland Public Schools contracts with Providence Health & Services for the athletic trainers who work with athletes and students in Portland schools. Aware of the relationship, and uncertain which entity had the schools’ records, van der Voo sought federal guidance on whether Providence or PPS owned the records — it was PPS — then coordinated conference calls with both before formally seeking the records. The strategy was intended to allow Providence time to check with its attorneys and compliance officers, and give proper direction to its staff before they received the request at their jobs at PPS.

Providence cleared a path for its employees to work with PPS to release the records within three weeks. However, repeated requests to PPS over the next four months did not produce the records. Threats to go to the district attorney to compel their release led to multiple false assurances that they would be coming soon.

It wasn’t until a school board member intervened — at the request of the Portland Tribune — that the records came through Feb. 27, more than five months after the initial conversations.

PPS spokesman Dave Northfield admits he dropped the ball on the request, but also noted the district receives an incredibly large volume of public information requests.

“It’s mainly just been a capacity issue,” Northfield said.

An appeal

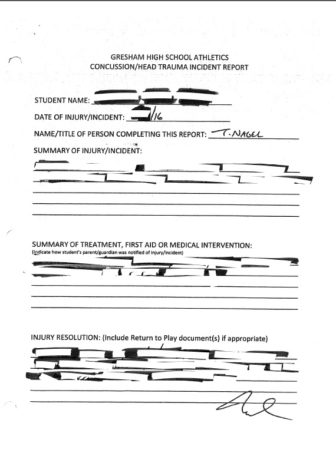

The Gresham-Barlow School District took a different approach in its Dec. 8 response.

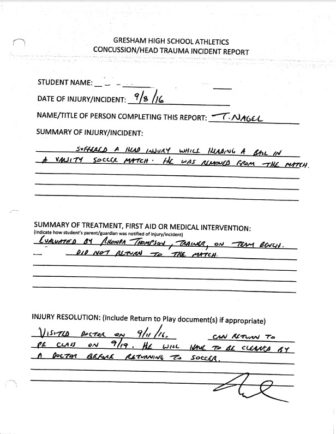

After intervention from the Multnomah County District Attorney, Gresham-Barlow School District provided the unredacted document above.

When district officials provided the records, nearly all the information on the return-to-play forms was blacked out.

The heavily redacted documents arrived after the Oregon School Boards Association initially instructed its member schools to edit the forms so that almost no information was readable — an opinion it later revised.

OSBA spokesman Alex Pulaski, a former reporter, said his organization provided sound advice to avoid liability that could come from violating students’ privacy rights.

“They could respond in a meaningful way, but not run afoul of their obligations under FERPA,” Pulaski said. He added that the association recognizes the public interest in head injury data and supports any effort to improve student safety.

“We know from the research we’ve seen in recent years that this is an area deserving of public attention,” he said.

InvestigateWest appealed Gresham-Barlow’s response and Multnomah County District Attorney Rod Underhill rejected the OSBA’s legal interpretation, ordering the district to re-release the documents with only student privacy information blacked out.

The redacted records were received the following week.

Responses, costs range widely

Beaverton School District initially claimed the forms were medical records and therefore guarded under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), van der Voo said. That exemption only applies to entities doing medical billing, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which van der Voo consulted at the beginning of the project. She ended up receiving a compilation of statistics from Beaverton’s records on Jan. 12 and is still determining whether they can be used.

Fees have been a stumbling block to many records. Oregon law only states that agencies can charge “actual cost” for compiling records and allows for a “public interest” fee waiver at the agency’s discretion.

Some districts, including Newberg, Forest Grove, Oregon Trail and Morrow, provided records without even tallying fees. Others, including North Clackamas, Lake Oswego, Sherwood, West Linn and Wilsonville, determined that release of the data was in the public interest and waived the fees.

Others, however, have sought to charge hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars for records.

In some cases, van der Voo said, the proposed fees exceeded the value of the data. For example, Colton High School in rural Clackamas County, which has 225 students, said it would cost $197.78 to provide copies of its redacted forms. Gladstone High School, with 737 students, said its fees would total $318. The school offered a fee waiver for two hours of labor associated with the records, but it was unclear how much the records ultimately would cost.

Some school officials cited internal policies that forbid fee waivers. Others had no policy or criteria as to when the public interest was met.

So far, InvestigateWest has paid $1,276.89 in fees to governments to provide public information. Another $5,782.57 in fee requests has been levied but not paid.

Shasta Kearns Moore is an education reporter for The Portland Tribune. She also volunteers as president of Open Oregon and co-chair of Freedom of Information Committee of the Oregon Territory Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.