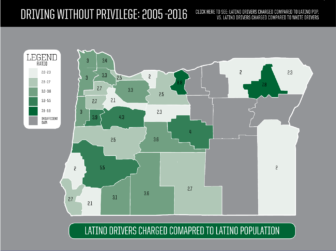

Latinos motorists in Oregon are far more likely than white drivers to be charged with motor vehicle violations

When Nubia Escobedo drove down to her father’s Woodburn grocery store, she forgot to take her driver’s license. You can’t blame the 18-year-old for being a bit distracted.

Her grandmother had fallen ill and her father, Ezequiel Escobedo Lopez, had just rushed back to Mexico to be at her bedside, leaving the family to run the store, which Lopez bought in 2011 to serve one of Oregon’s largest concentrations of Latino residents.

Escobedo agreed to cover a Thursday evening shift, and it was late when she climbed into her boyfriend’s Chevy Tahoe to drive back to Hillsboro. “My sister knew that I didn’t have an ID, so she was following right behind me, just in case,” she recalled.

As the cars headed north on Highway 99, Escobedo saw flashing lights in her rear-view mirror. An officer from the Hubbard Police Department told Escobedo he was stopping her because she’d veered out of her lane. “He was asking me for my ID right away,” she said.

Escobedo was handcuffed and placed in the back seat of a police car, where she promptly began to sob. “I was really scared,” she said. “I thought I was going to go to jail.”

Debate over disparities

Some authorities say that disparity simply reflects the fact that undocumented residents, who are overwhelmingly Latino in Oregon, can no longer get a driver’s license here.

But Nubia Escobedo — like 80 percent of Latino Oregonians — is here legally. And researchers who reviewed our analysis of 13 years of court records say that even when controlling for the estimated impact of undocumented immigration, Latino residents like her are charged with the most common offense — driving without a license — at more than twice the rate of whites.

What’s most striking to analysts who reviewed the data is that the disparity is seen every year we studied, from 2005 through 2015. That pattern, they say, makes it highly unlikely that the disparity is entirely due to the immigration status of drivers.

“In statistics you never say it’s impossible,” said Mark Harmon, a criminologist at Portland State University who reviewed our data and, specifically, the chance that the disparity for this charge was due solely to the immigration status of drivers.

“In this case, the probability (is) like 1 in trillions,” he said. “It’s so much smaller than being struck by lightning.”

What’s more, our review of court data, the first of its kind in Oregon, shows Latinos were more likely than white residents to be charged with driving without a license even before proof of legal status was required to get a license.

In a five-year period (2002-2006) prior to the state’s license restriction, Hispanics were charged at a rate two or more times that of whites in 16 counties. In a recent five-year period (2011-2015), that number didn’t change.

Latino residents are charged at higher rates with other driving offenses, too, including obstruction of vehicle windows, broken lights and failure to use lights, improper lane change, crossing the median, and failing to drive on the right.

Supporting the police

Many people we interviewed were troubled by our findings. State Rep. Sal Esquivel isn’t one of them.

“Maybe they drive different in Mexico,” said Esquivel, a Republican from Medford, whose father came to Southern Oregon from Mexico as a guest worker in 1945 and later became a U.S. citizen. “If they break the law, they break the law. That’s the end of the discussion as far as I’m concerned.”

Latino drivers drink and drive at a higher rate than white drivers, and they’re less likely to wear seatbelts, according to research by the federal Department of Transportation. But there’s no proof Latino residents are more likely to drive without lights, change lanes improperly or tint their windows.

So, why are Latino drivers racking up all these violations?

Many Latino residents, and lawyers who work with them, say it gets back to the driver’s license issue. Police, they say, target Latino drivers, pulling them over for minor violations so they can check for a valid license. Even some within law enforcement say Latino drivers in Oregon are pulled over for what’s known as “driving while brown.”

Retired Hillsboro Police Chief Ron Louie said he had to rein in a few officers who targeted Latino drivers.

If 20 percent of Latino residents are here without documentation, that might appear like good police work to pull over someone you know has a high probability of committing a crime.

But it’s illegal.

‘We all have bias’

Longstanding state and federal laws banning discriminatory practices based on race have always applied to police. But a 2015 state statute explicitly bars any law enforcement officer in Oregon from “targeting” an individual “for suspicion of violating a provision of law based solely on the real or perceived factor of the individual’s age, race, ethnicity, color, national origin, language …” unless that officer is looking for a suspect matching those characteristics.

That means police cannot target someone for criminal enforcement only because they appear to be a member of a racial or ethnic group, says Gilbert Carrasco, a former civil rights litigator for the federal Department of Justice who now teaches at Willamette University College of Law.

If enforcement is color-blind, members of any racial or ethnic group would be charged with most crimes at a rate that roughly matches their presence in the population.

And yet, our analysis of Oregon court records shows that Latinos are disproportionately charged with about a dozen crimes and violations, more than half of which are related to driving offenses.

Racial profiling is a hard allegation to prove in Oregon because the state doesn’t require agencies to collect information about who they stop.

Rep. Esquivel doesn’t think officers target people who appear to be Latino. “That’s a liberal argument. That’s something someone has made up,” he said. “If they’re guilty, they should be charged. And if there’s more of them charged, so be it.”

Hubbard Police Chief Bill Gill reflects on two decades of police work with both unwavering faith in his officers and unequivocal knowledge that they make mistakes.

“We are all human, and we all have bias,” he said. “On a daily basis, I evaluate how I’m doing my job and try to be honest with myself.”

Gill is adamant that the officer who stopped young Nubia Escobedo late one night in March 2015 didn’t do so because she was Latina. That doesn’t make him feel any better about a terrified 18-year-old who felt victimized by police.

“I’m not blind to the fact why people are so quick to feel that they’re victimized. Whether it was things that have happened to them, something they’ve heard, clearly there’s something going on here,” he said. It is “something we all have to be willing to work on, and be honest about.”