The data shocked even those who deal with numbers on a daily basis.

“I’m surprised at the size of the disparity,” said former Oregon State Supreme Court Justice Edwin Peterson. “I had no idea that the disparities are so great.”

Peterson was reacting to our analysis of 5.5 million state court records filed between January 2005 and June 2016, which showed that equal justice remains an elusive goal for the state’s more than 650,000 black and Latino residents.

“I’ve never heard that,” said Oregon Senate President Peter Courtney, upon hearing the data documenting racial disparities in the state’s criminal justice system. “I’ve heard stats, but it’s always been a national thing. I’m sitting there saying, ‘Where did you get that stuff?’ Those are pretty alarming stats.”

“It’s a little embarrassing if you’re doing a better job than government, but it’s not all that surprising,” said Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum, after a reporter shared some of the findings with her last week. “We should not be dependent on you.”

Among our findings:

• Latino Oregonians are nearly twice as likely as white residents to be charged with minor cocaine-related offenses, 2.6 times as likely as whites to be charged with prostitution-related offenses, and 6.5 times as likely to be charged with offenses involving a driver’s license.

• Black residents of Multnomah County are about four times as likely as white residents to be charged with prostitution-related offenses, nearly six times as likely as whites to be ticketed for offenses involving police and eight times as likely to be charged with robbery.

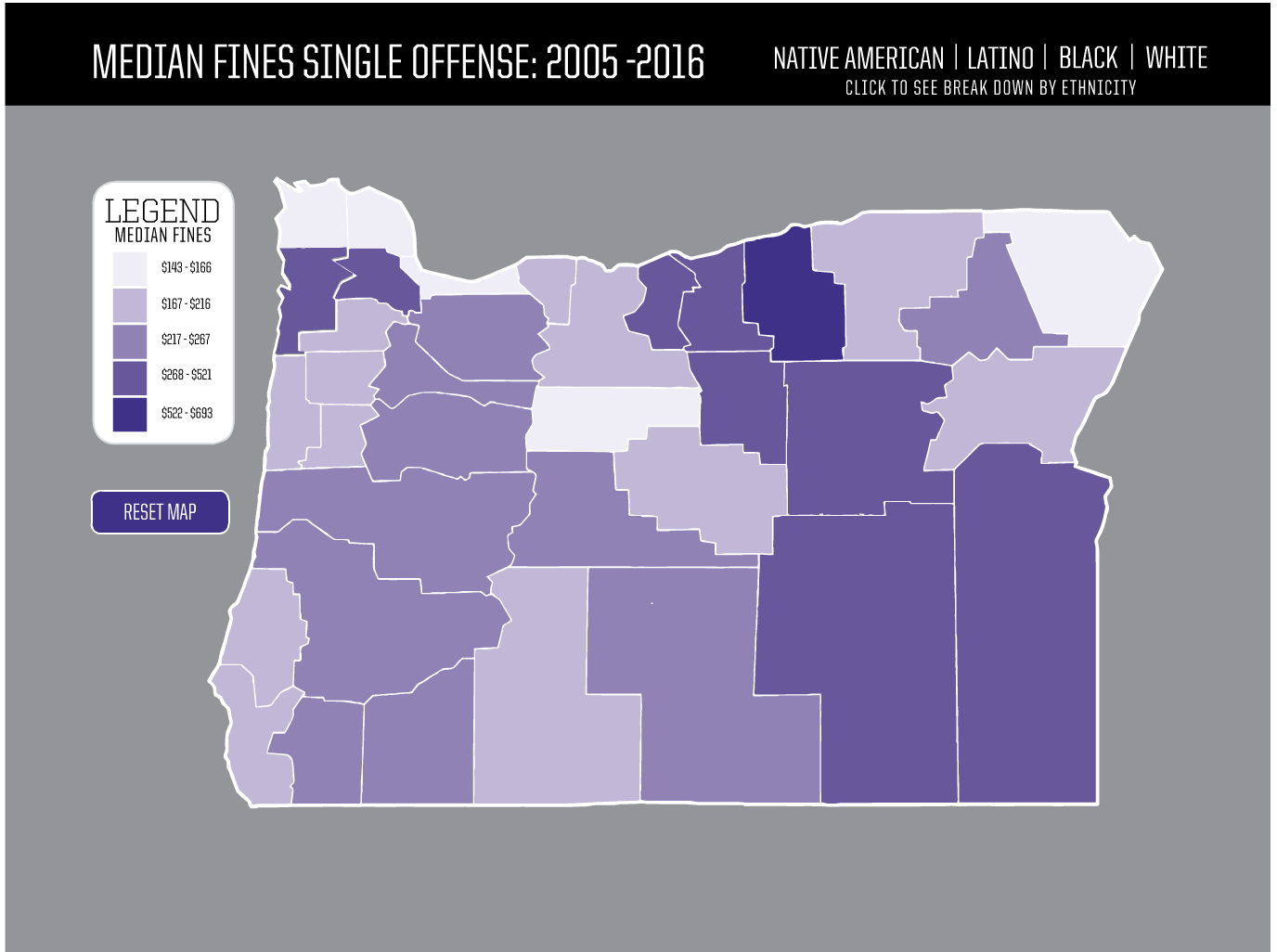

• Latino and black Oregonians pay higher median fines than whites. In Multnomah County alone, the gap between the fines for African-Americans and whites comes to as much as $2 million a year .

.

Longstanding problem

While our study is the first statewide examination of disparities that play out in the state court system, Oregonians have known for decades that people of color are more likely to be arrested, more likely to be charged, less likely to be released on bail, more likely to be convicted, less likely to be put on probation and more likely to be incarcerated than white residents, who make up nearly 80 percent of the state’s population.

In 1945, for example, the City Club of Portland wanted to know why African-Americans, who at the time made up less than 2 percent of Multnomah County’s population, represented 13 percent of the felons the county was sending to prison.

Portland Police Chief H.M Niles Niles said it wasn’t that his all-white police force was discriminating against African-Americans. Rather, it was his impression that black residents simply were more likely than white Portlanders to commit crimes.

We now know better.

Gap in crimes committed not as great

Crime and poverty are linked and people of color in Oregon, like everywhere in the United States, are more likely to be poor. But research shows that Americans of different races and ethnicities commit most violations and minor offenses at roughly the same rates. Yet black and Latino residents are far more likely to be charged for dozens of crimes in Oregon, from failing to use a crosswalk or using a turn signal, to interfering with a police officer and littering.

Over the past 18 months, we have taken a hard look at why that may be.

In some cases, we have found explanations that make sense. Latino Oregonians are charged at slightly higher rates than white residents for drunken driving. That corresponds with federal analyses showing Latino residents are more likely to drink and drive. But in other cases, there’s no clear reason why residents of color have a far greater chance of being charged.

For example, decades of research suggests white Americans use drugs, including powder cocaine, at higher rates than African-Americans. Federal statistics show that the only drug African-Americans consume at a higher rate is the crack form of cocaine, and then at less than twice the rate of white drug users.

Yet state court record data, which combine crack and powder cocaine offenses, African-Americans in Multnomah County were charged with cocaine offenses at a rate 30 times the rate of white residents.

In the coming weeks, we will detail our findings and show how these disparities impact people of color. Our series of articles also will highlight where data is incomplete or, in some cases, missing completely. The series will be published as state lawmakers gather in Salem, poised to address some of the issues revealed in our research.

Bill could reveal racial profiling

Attorney General Rosenblum has proposed legislation requiring that police track, among other things, the race and ethnicity of drivers they stop and pedestrians they search. If lawmakers agree to force local police to collect such “stop data” — and if the mandate is funded — it would close a huge gap in the information needed to understand the source of disparities in Oregon courts.

Gov. Kate Brown wants reforming harsh criminal sentences that disproportionately affect minority offenders.

And Oregon Supreme Court Chief Justice Thomas Balmer has launched a task force to root out racial bias in the courts.

Yet those who have been pushing reform for decades aren’t optimistic.

Jo Ann Hardesty, president of the Portland branch of the NAACP, spent six years in the Oregon Legislature representing part of Northeast Portland.

During her first term, in 1995, a series of bills aimed at addressing disparities in the criminal justice system were introduced. They were the result of two years of public meetings by an 18-person task force, which issued a 121-page report with 72 recommendations, including bias training, comprehensive data collection, and a review of sentencing practices. Only two bills, involving jury selection, passed in the 1995 session. The rest died, and efforts to revive them have been largely unsuccessful.

Those early efforts were the work of former Justice Peterson, now 86. He’s proud of the work, proud of a successful push to secure interpreters for defendants who appear in court. But beyond that, he said, he can point to little change.

“The racial discrimination problems that existed in 1992 continue to exist today,” he said. “Police officers continue to stop minorities at a higher rate, continue to search people of color at a higher rate. And agencies continue to arrest people at a higher rate. … It’s frustrating. It’s so frustrating.”

Hardesty and others are growing impatient.

“I don’t care how liberal you are or what your label is, I care about outcomes,” Hardesty said. If decades pass with no change, she said, “we’ve got the wrong people in office.”

Lee van der Voo contributed reporting to this article.

i doubt that much of this suppoed racial injustice is really about race, int he Courts. the courts oprate in a manne that requires a lot of money in order to hire good attorneys, or you have a high likelihood of losing your case no matter how unjust that may be. So look at the poverty aspect, which of course is not about race. As a white woman, the lack of money caused extreme harm and hardhip, suffering and early death in our family. the lack of money to successfully navigate the court system is the bigger threat by far. Justice is indeed blind, as it eludes poor people of all colors and races.