Escalating housing prices are driving racial minorities and low-income people to Portland’s fringe, a new analysis of housing and income data shows. Only whites and married couples with children have median incomes high enough to withstand rising housing costs in most parts of town.

That’s the news from the city’s first State of Housing in Portland report.

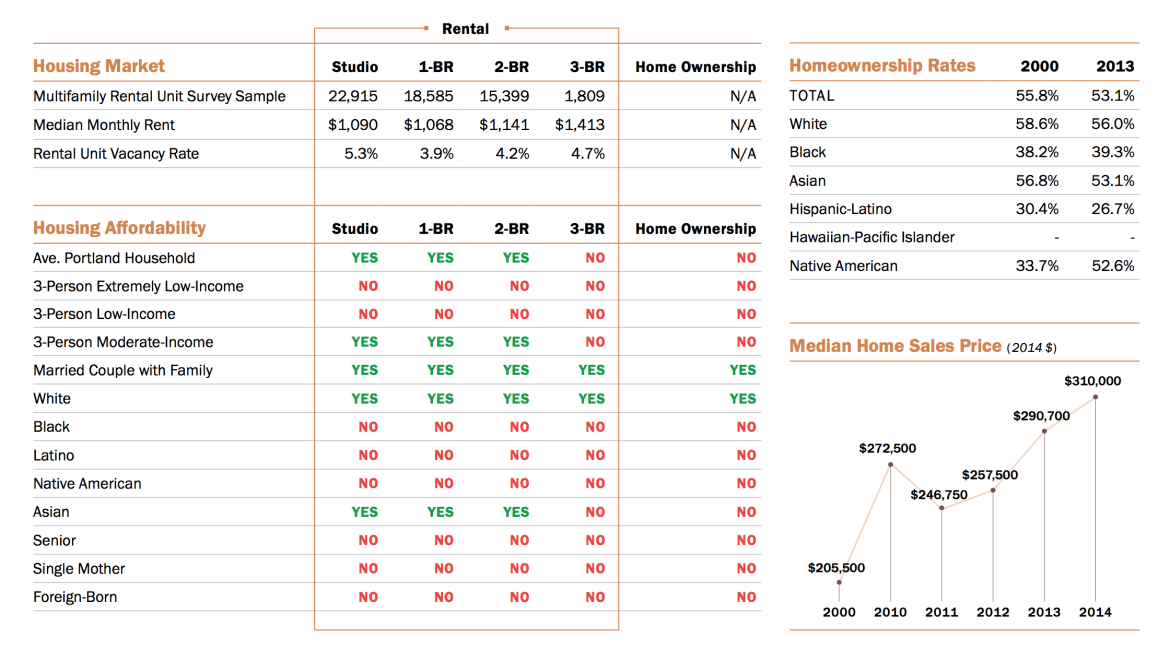

The effort by the Portland Housing Bureau, submitted in a report to the Portland City Council last week, tracks Portland’s housing and rental markets alongside median earning data. The housing bureau used Census data to determine the median income of different ethnic groups, then looked at how different racial groups, nontraditional households like single mothers or seniors, and a range of income earners would fare if shopping for housing from one neighborhood to the next.

The report found renters and communities of color haven’t seen the wage growth documented economy-wide — with those gains mostly captured by whites. As housing prices and rents rise, the report shows, housing options are severely constrained for lower income households, people of color, and single mothers and seniors.

When earning median income for their Census tract, single mothers have almost no chance of renting a home with more than one bedroom in Portland. A median-income black household can’t afford to rent anything bigger than a studio apartment outside the 122nd and Division neighborhood. Median-income Native American households are limited to studio apartments in Parkrose or Cully. And very low-income people are out-priced of the private housing market across the city, the report shows.

To an extent, this is not news. The report confirms what many suspected: Portland is becoming increasingly white and well-to-do, while housing options for social and racial minorities dwindle. It also indicates that Portland’s housing affordability is at a tipping point — with rents and home prices outstripping the means of even an average Portland household. Even white households earning median income are priced out of many of the city’s neighborhoods, as are Asian households earning median income.

“I believe the data from the State of Housing report perfectly illustrates what we have seen and know to be the case of Portland,” said Bishop Steven Holt, who leads the International Fellowship Family church and a city committee to oversee strategies to lessen gentrification’s impacts in North Portland and Northeast Portland, in an email. “Portland is becoming the dwelling place for the elite.”

Holt points to young people just starting careers, as well as racial minorities, and says all are under economic pressure that makes it tough for them to thrive rather than just survive in Portland.

Such data bolsters longstanding concerns about Portland’s housing costs, and charts a path toward policy intervention. (InvestigateWest reported earlier this month on the inflationary impact of cash sales in the local housing market.) Portland Housing Bureau officials and City Commissioner Dan Saltzman, who oversees the bureau, say they will spend the next several months gathering feedback on the data for a second-phase report in the fall that includes policy solutions.

For some groups, phase two can’t come soon enough. “We’re all anxious to work with the city on coming up with solutions,” said Diane Linn, the former Multnomah County commissioner who is now executive director of Proud Ground, a community land trust that helps people earning 60 to 80 percent of the median income buy homes.

Proud Ground buys land with houses on it, selling the housing to qualifying homebuyers who can stabilize their families and neighborhoods. Because buyers are paying only for the house, and not the land, they spend a lower percentage of their earnings on housing. Proud Ground’s mission always has been challenging.

“In this market? It’s just making it harder and harder,” Linn said.

Even average-earning Portland households can’t afford to buy a home in more than half of the city’s neighborhoods. Low-income earners — households earning 30 to 60 percent of median family income — are nearly completely out of luck, as are Latino households, seniors, single mothers, and foreign-born homeowners.

The demographic that had the highest median income and the most housing options was married couples with children, at $88,088 a year, followed by whites, moderate income earners and Asian households. Black and Native American families are completely priced out.

Those issues run deeper than the cost of housing, says Holt. They also speak to the growing pay inequity between racial groups in Portland.

“It’s not simply a housing issue. When we talk about affordable housing or low income housing, for me its why are folks still low income?” he said. “The bigger issue for me is economic opportunity.”

The report showed communities of color are now concentrated at the periphery of the city. There’s some indication — though unconfirmed — that some African American and Native American households are simply leaving the city. The report also found that renters’ income is not keeping up with rising rents.

Those disparities were acknowledged by city commissioners, who heard details of the report April 29. Mayor Charlie Hales said income inequality clearly combines with pressure from new Portland residents, many who hail from more high-priced housing markets, to boost housing costs.

“Like it or not, hate it or love it. Want to stop it? Good luck. But those two forces are lighting us up,” he said.

The data indicates the city’s urban renewal areas are among the least affordable places in town, with all but two-parent white families priced out of four of nine of the areas. Racial minorities and low-income households have access to housing in even fewer urban renewal areas, indicating that the state’s ban on inclusionary zoning — a zoning policy that forces developers to include low-income units in new construction — has helped to foster racial and economic divides in Portland.

The city has meanwhile invested a portion of taxes captured in those urban renewal areas into affordable housing units throughout town. Portland partly funded 65 percent of the affordable units currently available in the city. But those taxes set aside from urban renewal areas are now declining.

Meanwhile, single-family home production is lower than ever. Data shows new construction is concentrated in the Interstate Corridor, followed by Lents-Foster, MLK-Alberta, and St. Johns, indicating that a portion of new construction is replacing older and more affordable housing stock.