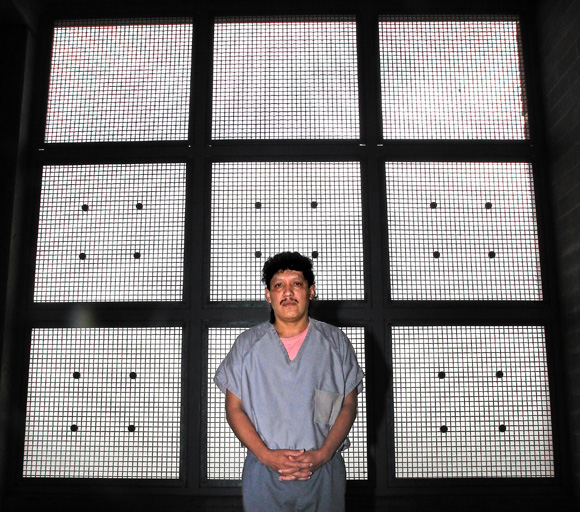

Cruz Velasquez served a 60-day sentence for a DUI conviction in the Pierce County Jail in 2011. Held on a immigration detainer, he feared he might be deported.

Dean J. Koepfler/The News Tribune

He came to America for a better life, to flee the fallout of a bloody civil war and the gang violence that now infests his native El Salvador.

For more than 15 years, Cruz Velasquez says he had found that life here – in Tacoma, in America.

He found it in a job as a window installer that, by U.S. standards, pays near poverty levels but earns him more money than he’s ever made.

He found it in Juana, a fellow illegal immigrant who bore him a daughter and a son – both American citizens, each delivered in good health at St. Joseph Medical Center.

And he found it in the home all of them now share: a modest rambler with a big tree in the front yard in South Tacoma.

But last summer as he awaited the end of a two-month term in the Pierce County Jail for driving under the influence – and the arrival of federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers to escort him to a privately operated detention center on Tacoma’s Tideflats – Velasquez knew the life he built here could vanish.

“If it happens, if I get deported, I wouldn’t want my children to go,” Velazquez said through a translator last August. “In El Salvador, there is trouble with gangs and just violence in general. I would prefer my children stay in the United States.”

Velasquez wasn’t giving up his family just yet.

“I’m going to fight to stay here,” he said.

He’s been fighting all his life. Born in 1968 in Cabanas – a sugar cane-rich region in central El Salvador – Velasquez was a slight 8-year-old when war gripped his country and forever changed daily life.

“I stopped school in second grade because we would always be running from one place to another, in the middle of the night,” he recalled. “So, my youth essentially went away.”

For most of his childhood, Velasquez and his family survived by farming corn and other crops for subsistence. He also worked to avoid gang violence that infested El Salvador, where over a span of a dozen years more than 75,000 people were killed.

“The gangs were always recruiting, so you had to be on your toes,” he said. “I tried hard not to be involved in any of it.”

The best way to avert the violence, Velasquez believed, was to flee to America. In May 1996, he followed a coyote – a human trafficker – across the desert wilds of the Mexican-U.S. border at Arizona. His first four attempts, border agents caught him.

“I would pretend to be a Mexican, so every time, they’d turn me back to the Mexican side,” he recalled. “And what would happen was I would find someone else who was crossing that night, and I would try again.”

On his fifth try, he made it. A fellow Salvadoran who was living in Tacoma drove to meet him at a hotel in Phoenix and paid the coyote a $1,200 fee.

Velasquez’s first few months in country were lean. When he couldn’t find work in Tacoma, he moved to Washington, D.C., to take a job cleaning federal government offices.

He later obtained an 18-month work permit that the Immigration and Naturalization Service then granted especially to immigrants from the war-ravaged Central American nation.

Velasquez later moved back to Tacoma, eventually landing work at a small window installation business. Over eight years, he climbed the pay scale to a salary just over $37,000 per year.

He also met Juana, a single Mexican mother of two teenage girls. The couple soon welcomed their own children, daughter Yajuira Jocelyn, now 5, and son Alexis Josue, 2.

Velasquez’s salary, after taxes, was enough to support his family in Tacoma, as well as his mother, a blind widow who still lives in El Salvador.

“I send her from $150 to $200 a month,” he said. “I should send her more, because my sister who takes care of her also needs to eat and she has children. But I cannot send more because I also have my own bills – my rent and my other expenses.”

A few years ago, when Velasquez’s work permit expired, he tried to renew it by proving his continuous U.S. residency.

“I sent them a utility bill in my name, but they said it was too old,” he said. “They wanted a more recent bill that I couldn’t find.”

In general, an alien is required to prove continuous residency “for extending a temporary protective status,” said Sharon Rummery, a spokeswoman for the federal Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services.

On June 4, 2011, a state trooper stopped Velasquez while driving because he wasn’t wearing a seat belt. The trooper found three open cans of beer on the passenger-side floor.

Velasquez claims the open containers belonged to his passengers. Nonetheless, troopers say he failed a breathalyzer test. Velasquez later pleaded guilty to driving under the influence – his second DUI conviction in five years. He drew a 60-day jail sentence and a $2,100 fine.

He also drew an immigration detainer – something that didn’t come after his first conviction in 2005.

“Immigration came to talk to me here, as soon as I arrived in jail,” he said.

An ICE spokesman said last month the agency has no records about Velasquez from 2005, so can’t say why he wasn’t detained then.

Just two days from a trip to the Northwest Detention Center, Velasquez feared he would never again hold his children as a free man.

“My family already paid for a lawyer,” he said of Juana and her relatives. “The only thing that I’m missing is the money for bond. They say it’s going to be steep — $8,000 to $10,000.”

If he can’t bond out, Velasquez likely will face a deportation hearing much faster while in detention. His days in America could be numbered.

“If I have to go, I am thankful for this country,” he said. “If I have to go, I will hope to come back someday.”

But on Sept. 21, about a month after his transfer to the detention center, Velasquez managed to raise the money needed for his release.

“Mr. Velasquez remains out of custody at this time while his removal case is pending with the immigration courts,” Andrew Munoz, Seattle’s ICE spokesman, said in July.

Velasquez has not responded to a reporter’s multiple attempts to contact him since his release.

Nicolás Pinel, a Colombian-born volunteer translator who is trained as a translator for courts, translated Carrada’s comments for this story.