Eight times in seven years, a state inspector asked Joe Lemire to keep his cattle off the banks of Pataha Creek. Why? Because they drop cow pies in the water. Cows trample pollution-filtering streamside plants. Cows mash the banks down so dirt gets into the stream, which had been targeted for cleanup by the government since the early 1990s.

The state even offered to pay for fences to keep the cows out of the stream.

But Lemire refused. He fired back that the state couldn’t prove his cows were polluting the stream, which cuts an undulating path deep into the volcanic plains of southeast Washington. When the state issued him a formal order in 2009 to keep the cows away from the creek, Lemire appealed to a state pollution-hearings board.

This fall his case heads to the Washington Supreme Court in what is shaping up as a pivotal decision about farmers’ obligations to protect Northwest waterways. In a related struggle, Indian tribes are charging that farmers such as Lemire are killing salmon.

Lemire is a 69-year-old retiree raising cattle and hay. He’s become a cause célèbre in the countryside, where farm bureaus are soliciting residents to send money to cover the costs of his legal fight.

“I was guilty until proven innocent,” Lemire said in an interview. “It makes it mandatory for me what’s voluntary for other people.”

He has a point. Forty years after Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the Lemire case highlights one of the biggest failings of this bedrock environmental law: farms are exempted from federal water-pollution regulation.

Farmers are regulated by the states. With a few exceptions such as the Lemire case, those who pollute are likely to face a stern talking-to or simply an offer of technical assistance – maybe even with some taxpayer money attached. A fine? That’s much less likely for a farm or a ranch.

Yet agriculture is the biggest single reason America’s rivers and streams fail to meet Clean Water Act standards, according to a November 2011 federal report.

“Agriculture hugely undermines the success of the Clean Water Act,” said environmental law professor Oliver Houck of Tulane University. “The Clean Water Act was spectacularly successful –- but like all great successes, there’s a huge flaw, and the flaw is agriculture.”

When Congress decided in 1972 to leave farm pollution to the states, part of the reasoning was that agricultural pollution was less critical than the widespread toxic industrial dumping that left urban rivers in flames in the 1960s.

Video courtesy of the Oregon State University Archives.

Congress figured that agriculture and its twin pillar of the rural economy, logging, varied so much from place to place that regulating them ought be left to states, which would be most familiar with the local practices.

The result today: If Lemire ran a sewage treatment plant or a factory, he would unquestionably be obliged to clean up gunk going into Pataha Creek. The Clean Water Act demands it. But because Lemire is a farmer, the federal law leaves it to the state to guard against agricultural pollutants, and that’s far from a sure thing. Normally farmers across the Northwest get the same offer Lemire did originally: help from the government, not a fine. The fact is, it’s pretty unusual for government to go after a farmer for polluted rainwater runoff.

Back when Congress acted, this might have been hard to foresee. Yet Congress’s action 40 years ago has consequences today across the Pacific Northwest:

- Washington regulators say they must think twice before using their state’s strong water-pollution laws or risk angering state legislators.

- Idaho’s Department of Environmental Quality acknowledged in an April 2011 document that “political constraints” plague its efforts to produce waterway-cleanup plans.

- In Oregon, regulators don’t actively monitor most of the state’s 38,700 farming operations, with the exception of 532 large operations. (They do look into complaints from the public and also open investigations if they happen upon a water-quality violation while they are in the field.)

A review of government records by EarthFix and InvestigateWest also found that heat –- a major byproduct of agricultural pollution — is the leading reason Pacific Northwest waterways fail to meet the goals of the Clean Water Act.

Meanwhile, the Clean Water Act requires the government to devise cleanup plans for polluted waterways. But putting those plans into effect? There is no requirement that farmers follow what’s outlined in them.

Should farmers face mandatory regulations?

Washington and Oregon, unlike many states, have authorized their regulators to compel farmers to reduce water pollution. And yet nearly 36,000 miles of rivers and streams associated with agriculture remain polluted in the Northwest to the point they don’t meet the goals of the Clean Water Act, according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency records.

State officials say they must tread gingerly when they try to rein in agricultural pollution.

“Unfortunately, having the authority to do it doesn’t mean, politically, that you always can,” said Helen Bresler of the Washington Ecology Department, which enforces the Clean Water Act in Washington. “That makes a difference.”

Oregon’s agricultural program for water quality relies upon a mostly voluntary compliance approach, offering farmers and ranchers technical assistance and education on issues such as manure management. The goal is to help them manage their land in ways that protect nearby water bodies. The agency, however, does not know if that approach is working.

“We have not received sufficient dollars to monitor the success of our programs,” said Ray Jaindl, the administrator of the Natural Resources Division of the Oregon Department of Agriculture.

From the agricultural industry’s point of view, regulation already has gone overboard. Dairies and other intensive livestock operations, for example, received increased scrutiny in the last two decades as so-called “confined animal feeding operations,” subject to regular inspections just like a factory or sewage plant. And four have been fined collectively more than $100,000 in recent weeks in high-profile cases in Oregon and Idaho.

Industry representatives say the traditional deference to farmers makes sense.

“What we’ve pushed hard is voluntary measures,” said John Stuhlmiller of the Washington Farm Bureau. “Let folks do the right thing. Help them understand what the issue is, and if there’s a real threat or a real need to do something different, folks will step up to the plate and do it. Just provide the right incentives, rather than disincentives.”

“A heavy regulatory scheme … just doesn’t encourage people to do the right thing. It makes them afraid, if you will, and that isn’t the positive mode that we need to be in.”

IMPAIRED WATERS IN THE NORTHWEST

NOTE: Each state — and the EPA in Idaho — has a different system for assessing its waterways under the Clean Water Act. This partially explains why Washington, Oregon and Idaho appear to have variations in the waters they have listed as impaired.

Environmental groups say that’s a mindset that needs to change — given agriculture’s large contribution to the remaining pollution problems — if we aim to make waterways fishable and swimmable.

“When the Clean Water Act was written they looked around and said, ‘What’s the biggest source of the problem?’ And the biggest source of the problem was industry,” said Justin Hayes of the Idaho Conservation League. “These were the huge problems and they were addressed first, as they should have been.”

“So now it’s time to turn our attention to some of the other problems,” he said.

Northwest’s biggest water polluter: Sunlight in a logged-off world

Up against the Continental Divide on Idaho’s eastern flank sits the Salmon River Basin and its numerous watersheds.

One of them, the Lemhi River Valley, is a picturesque slice of high desert canyons, grassy foothills and mountain forests beneath the Beaverhead Range that marks the Montana border. In the two centuries since Lewis and Clark passed through, the valley has been transformed into an 80-mile-long series of grazing lands and alfalfa fields. And that’s had consequences for the health of the river, which once supported large populations of salmon and trout.

Some of the earliest homesteads in the Salmon River Basin during the late 1800s had numerous salmon and steelhead spawning in the streams and rivers in their backyards. Jimmie Martiny’s family has worked the land here for four generations. He recalls stories his grandmother told — what it was like to hear the fish come up the river.

“She said it sounded like a herd of horses coming. Of course, that was a long time ago,” Martiny said.

As recently as the 1960s, biologists counted more than 3,000 salmon nests, or redds, in the Lemhi River. But over the last 40 years, the demand for water to raise both cattle and alfalfa has increased so much that by the late ‘80s and early ‘90s the Lemhi and its tributaries frequently ran dry. That’s still happening today.

By the mid-1990s biologists found fewer than a dozen salmon redds. Lots of factors conspired to wallop fish populations, but biologists say a major impediment is that the Lemhi and its tributaries have grown too warm for salmon and trout, which need very cold water to survive.

Warm water contains less oxygen than colder water. If a stream gets hot enough, fish die, either because of heat stress or from suffocation. Heat can also mess up the fish by increasing their metabolic rate, so the fish burn more energy than they can get by eating, leaving them spent and vulnerable to predators.

Cutting down trees and exposing a river’s tributaries to direct sunlight is just the first of many steps that translate to warmer-than-natural waterways. And what’s happening in the Lemhi is happening across the Pacific Northwest.

“Temperature is a reflection of all the bad things humans have done to the landscape that have affected our water quality,” said Nina Bell of Northwest Environmental Advocates, a Portland-based group.

Based on the findings of scientists from several federal agencies, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency told states that streams that are expected to support coldwater-loving salmon need to be kept cooler if they are to meet the goals of the Clean Water Act. The EPA is ultimately responsible for enforcing the act.

Researchers say the effects of elevated water temperatures on fish are comparable to a human who has run too long in the heat without eating or drinking. One of the scientists advising EPA was Jason Dunham of the U.S. Geological Survey, who said the effects of too-warm waters on fish is “they come undone. They experience physical damage: proteins start to unravel –- proteins that are important for bodily functions, enzymes.”

Lemhi River. Credit: EarthFix

The federal government’s position has been controversial across the region, although the controversy runs deepest in Idaho, where farm groups say the EPA has gone overboard, requiring keeping the water cooler than is practical or necessary. And in this fight, Idaho’s agricultural lobby has found a sympathetic ear at the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. for years, the department has disagreed with the EPA over the water-temperature issue.

Southern Idaho, in particular, is a desert environment where salmon and their relatives boomed for millennia and can hang on today, no matter what EPA’s tests show, argue Idaho DEQ and the farmers.

“EPA developed its standards based on laboratory tests of fish,” said Michael McIntyre, head of the Idaho DEQ’s surface-water management branch. “That’s obviously a different situation and effects on the fish than you’d find in the wild.”

But environmentalists say it’s crucial for the Clean Water Act to support cold waterways.

“If you take a trout stream and you do something on the banks — you cut all the trees that line the creek away from the banks, you let the sun really beat down on that creek — that solar radiation will warm up that creek and what was once a great trout stream will be too warm for trout to spawn and for young trout to grow,” said the Idaho Conservation League’s Hayes. The league has twice sued the state of Idaho over the temperature issue.

The federal government’s basic solution for many years has been to offer farmers money to help them do the right thing. All three Northwest states give technical assistance to farmers through conservation districts. There, farmers can learn “best management practices.” They may even be able to pick up government funding to help put them into effect.

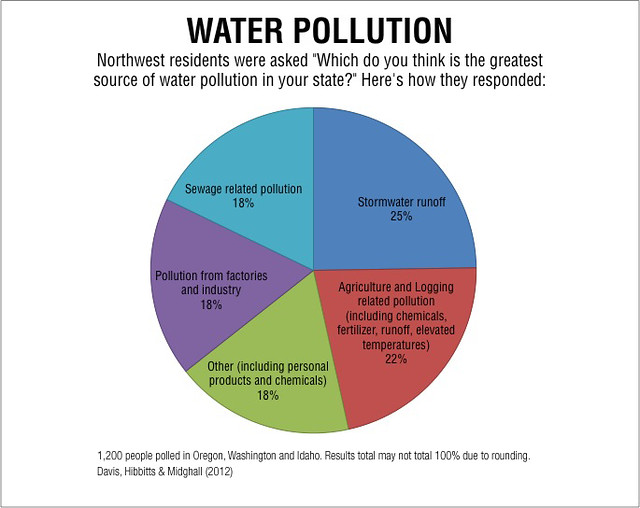

Click here for a PDF of the EarthFix Poll’s agriculture-related survey questions and responses.

Some of the money to help farmers comes from a grant program launched in 1990 to help states start to get a handle on the kind of pollution that flows off farms – “nonpoint-source” pollution, in regulators’ lingo. By 1999 Congress, realizing the enormity of the problem, doubled the amount of money going into the program, to nearly $200 million annually.

Those projects included planting stream-side trees to filter out pollutants and provide shade. Once that funding trickles down to Idaho, Washington and Oregon, though, it amounts to a just a few million dollars per state per year. Even counting additional money put in by the states and others, what these projects get “is a drop in the bucket,” said Dave Croxton of the EPA, who oversees development of cleanup plans and water-quality standards for the agency’s Seattle-based Region 10.

And now even that drop is getting smaller.In the last two years, for the first time in a dozen years, Congress has cut the program below $200 million. This year it is receiving about $165 million.

Planning for cleanups – but not doing them

At the current rate the United States is cleaning up its waterways, it will be 500 years before they’re all restored, according to an EPA report issued late last year. When a waterway is classified as “impaired” under the Clean Water Act – meaning it’s too polluted to allow swimming or fishing or other commonly expected uses of a waterway – the state is supposed to catalogue the pollution sources and put together a cleanup plan.

The problem is, the law doesn’t require that those cleanup plans be fully carried out.

The cleanup plans are known as “Total Maximum Daily Loads,” or TMDLs, because they’re supposed to spell out which polluters in a given watershed can dump how much pollution in a given day without fouling the waterway. That theoretically works great if you’re talking about a sewage treatment plant or a factory that is legally bound to get a permit from the government to dump pollution into a waterway. The government just tightens the pollution limits.

Farms by and large don’t require such government permits, however. So most are not as tightly regulated. Instead the government would like for them to comply with “best management practices” that critics say too often are vaguely defined, or not followed at all. Part of the reason, these critics say, is that the “best management practices” are loosely enforced, with the Lemire case being the exception rather than the rule. Lemire’s cows are 21 miles upstream from the sewage treatment plant at the tiny town of Pomeroy has been trying for more than a decade to clean up its end product so that the stuff being dumped into the creek would meet the requirements of the Clean Water Act. The town of 1,400 people, with the aid of federal and state taxpayers, has sunk $2.4 million into improving the treatment plant over the last decade.

Today the town of Pomeroy has won state recognition for its extraordinary and expensive efforts to ensure the town’s sewage doesn’t overwhelm Pataha Creek. Yet Lemire still is letting his cows drop feces in the same stream, Ecology says. And he’s appealing to the Washington Supreme Court to keep it that way.

“We hopefully don’t have that problem anymore because they’ve [Ecology] finally convinced the farmers not to let their cattle walk around, wander into the creek to drink,” said Glenn Davis, wastewater plant operator for the city. “They’ve got them fenced back.”

While that is true for most farms along Pataha Creek, it isn’t at Lemire’s place.

Jack Fields, executive vice president of the Washington Cattlemen’s Association, said his group jumped into the Lemire lawsuit as a matter of principle and practicality.

“It’s huge on a statewide basis because we can’t simply have the agency drive by and say, ‘Oh, there’s a cow, that guy’s gotta be out of compliance,’” Fields said. “There’s got to be data to back up the charge.”

“A considerable political reaction”

Farther west, along the Pacific and Puget Sound coasts, animal waste is one of the main contributors to pollution that shuts down shellfish harvesting on a regular basis. Yet even where a cleanup plan is devised and state regulators take action, politics sometimes interfere.

For example, not long after Washington state completed a cleanup plan for Samish Bay, heavy rainstorms in 2010 washed so much pollution into the bay on Puget Sound’s eastern shore that some six square miles of oysters and other shellfish had to be closed to harvesting. It was the 17th time shellfishing in the bay had been halted since 2008.

The Samish carries some of the highest levels in the state of fecal coliform, a type of bacteria found in the gut of warm-blooded animals that indicates the possible presence of pathogens that will cause intestinal upset or even more serious disease.

Washington’s Ecology Department swung into action, citing a farmer and spreading the word that other landowners would have to take steps to keep manure from washing into nearby waterways.

“We issued an enforcement order and very soon after that a bill was (introduced) in the Legislature to take away our ability to enforce this law,” said Bresler, Ecology’s watershed planning unit supervisor, who added that lawmakers at the time also considered taking away federal pollution-control dollars. “It was an interesting exercise in what happens when we use our enforcement power.”

“There was a considerable political reaction” to Ecology’s crackdown, agreed Josh Baldi, special assistant to Ecology’s director. Baldi was stuck fighting off several pieces of legislation in the 2011 legislative session that would have made it much more difficult for Ecology to bring enforcement action against agricultural polluters.

A few months later, Gov. Chris Gregoire learned of the episode and insisted immediately that more action be taken.

“We need to accept the fact that we’ve failed and take immediate steps,” Gregoire said in April, 2011.

Farms near Samish Bay. Credit: Joe Kunzler/Creative Commons

Ecology inspectors visited more livestock operations in the watershed. A few were fined but most were referred to the Skagit Conservation District, a farmer-friendly agency that provides voluntary options and incentives.

Mike Shelby, executive director of the Western Washington Agricultural Association, said fecal coliform in the Samish River doesn’t come only from livestock. Other contributors include people’s septic tanks and sewage-treatment systems, as well as dogs and waterfowl, Shelby said.

“Every individual that lives in the watershed is responsible for some part of it,” Shelby said.

Shelby said the system of referring most farmers to the local conservation district makes sense because what farmers need is education, not enforcement.

“Nothing is simple,” Shelby said. “This problem we’re finding is much more complicated than what anyone thought when this started. It’s going to take a serious effort on everyone’s part to educate everyone in the basin.”

Patience is wearing thin for some Indian tribes, though.

Over the last year the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, an umbrella group that works for 20 tribes in western Washington, has peppered state and federal officials with strongly worded letters saying, in essence, that regulators’ efforts to protect waterways aren’t working – and therefore, salmon aren’t coming back, and therefore, the government is effectively breaking treaties with the tribes dating to the 1850s.

A lot of the problem has to do with agriculture, the tribes say.

“Best management practices have become nothing more than (what) agricultural landowners are willing to do, under the rationale that any attempt to improve water quality is better than doing nothing,” the tribal commission wrote to a May 18 letter to Washington’s Ecology Department. “This position has become untenable.”

In the Samish, a tribal organization has been equally outspoken about the need to reduce agricultural pollution.

Since the governor got involved, “It looks like they’ve increased the enforcement effort, but unfortunately it doesn’t look like the current efforts are resulting in measurable water-quality improvements,” said Larry Wasserman, environmental policy manager at the Skagit River System Cooperative, which manages natural resources for two tribes.

Over the last year, directors of Washington’s Conservation Commission and departments of Ecology and Agriculture have been discussing what to do about agricultural pollution.

At Ecology, Bresler said the agency is going to try something new: In cleanup plans, the agency will ensure that it’s spelled out who has to reduce pollution and by how much – including farmers. Also, the agency will be specific about which kinds of land uses are contributing to the problem – which is tricky, she said, and bound to be controversial.

“It’s always easy to argue,” Bresler said. “Everybody will argue about it but if you don’t start, you won’t get there.”

Ecology’s Baldi says there is a growing awareness among environmental regulators that agriculture must reduce its pollution levels.

Still, Baldi said, Ecology will always think twice before using its enforcement powers.

“Is there clear environmental damage? Do we feel we have a good legal footing should we be challenged?” he said. “Do we believe politically we can sustain this? That’s an important policy consideration. That’s the way the system works.”

Bonnie Stewart, Courtney Flatt, Aaron Kunz and Jason Alcorn contributed to this report.

There’s more to come in our series, “Clean Water: The Next Act:”

- Waterways increasingly contain potentially dangerous residues of the lotions, potions and pills that keep us well and clean and smelling nice – a threat the Clean Water Act was never intended to stem.

- Sewage treatment remains a major source of water pollution, with increasing numbers of governments struggling financially and beset by aging wastewaster treatment facilities.

- Development-related pollution in the form of rainwater runoff poses an increasing threat to water quality.

Let’s get something straight. The biggest source of water pollution is not what most would call “agriculture”, (food grown for human consumption) – it is the result of cattle farming and the growing of crops to feed the cattle.

If we are serious about cleaning up our water we must change our diets. And we should start charging cattle farmers the same high price for water that other farmers have to pay. Grow food directly for human consumption. There are all kinds of efficiencies and benefits to be realized by getting rid of beef in our diets.