Athletic trainers, placed in every Hawaii high school, help prevent and treat concussions

HONOLULU — When the Roosevelt Rough Riders of Honolulu hosted the PAC-5 Wolfpack in the opening round of the Hawaii High School Athletic Association state football playoffs on Nov. 10, Scott Yano was, as usual, pacing the sidelines.

Yano, a key member of the Rough Riders, didn’t line up for a single snap or mark up an offensive play on the sidelines. But everyone knew he was there for them as one of two athletic trainers employed by the Honolulu school, ready if any student suffered an injury.

You’ll see athletic trainers at some high school events in many states, including Oregon. But Hawaii is the only state in the country to ensure that at least two trainers are working at every public high school.

These certified health professionals specialize in sports medicine and work to prevent student athletes from becoming injured and, if they do, overseeing their treatment, rehabilitation and return to the field.

In Hawaii, the presence of athletic trainers is a given — they are considered an essential part of any school’s athletic program and play a key role in preventing concussions and helping those student athletes who do suffer concussions recover and return to both the playing field and the classroom.

The state earmarks $4.28 million annually in the public school budget for the 74 positions. Yano was one of five athletic trainers observing the Nov. 10 football game, which is typical in Hawaii.

Research increasingly links the presence of an athletic trainer in high school sports programs to lower rates of injury, as well as better management and treatment of student athletes — including those who suffer concussions.

In Oregon, a just-completed analysis by Pamplin Media Group, InvestigateWest and Reveal shows that Oregon high schools that have athletic trainers are much more likely to identify and treat concussions than schools without them.

That finding, which was based on a review of more than 2,000 public records, mirrored findings of a joint research project by the University of Wisconsin, the University of Michigan and San Diego State University. The study evaluated the varying degrees of access that 2,459 Wisconsin high school athletes had to trainers. Their results, published in the November 2018 Journal of Athletic Training, found that the availability of trainers “positively influenced” reporting concussions, as well as post-concussion management.

In Hawaii, where athleticism is valued and recreational opportunities abound, the role of an athletic trainer is viewed not as a matter of improving athletes’ performances, but, rather, protecting their health and safety.

“When I first started, my athletic director basically told me that you’re here for the kids, the health and safety of the kids,” says Troy Furutani, a former high school athletic trainer who now works as director of the Hawaii Concussion Management Awareness Program (H-CAMP).

“Just the fact that you had a person that was designated to take care of children playing sports has been the key,” says Glenn Beachy, who was the second athletic trainer to ever work in Hawaii, working as the athletic trainer for Punahou School, the largest private school in Hawaii, for much of his 50-year career before retiring in 2017.

Athletic trainers, Beachy says, “have made a big difference for the athletes, there’s no question. You see kids that are much better conditioned and understand the treatment and the importance of doing rehab.”

A culture of caring

Many sources interviewed for this story say having an athletic trainer at every school is a no-brainer given the value Hawaiian culture places on community and children.

“It’s a very familial-oriented culture,” says Nathan Murata, the dean of the University of Hawaii Manoa’s College of Education, which oversees H-CAMP. Murata adds that it is natural for Hawaiians “to take care of each other, to look out for each other, to support each other.”

Athletic trainers in Hawaii teach athletes how to safely warm up, cool down and train, as well as emphasize the importance of sleep, nutrition and hydration. And, of course, how to safely play the student’s sport of choice — from how to fall and land properly in judo to how to avoid tackling with their head in football.

“Their main role is making sure that there’s a health and safety factor” in sports and practice, Furutani says. “If somebody is injured, they’re able to manage it appropriately, if it’s a potentially catastrophic type of situation, with a neck injury or a head injury that they’re able to manage it on the field.”

And their word on matters of health and treatment is final. “Whatever the athletic trainer decides, that’s the way it’s going to go,” Furutani says. “If the kid’s out (from playing), the kid’s out. If he needs to see a doctor, he needs to see a doctor.”

In Hawaii, the athletic trainers attend every practice and every home game of all the sports teams at their school. They also travel to all away games with the varsity football team and, at times, other high-injury sports, such as basketball or soccer, to provide emergency care to injured athletes.

On non-game days, they work with every student athlete who’s been injured, providing ice and heat therapy, taping and rehabilitative and stretching exercises. They make referrals to physical therapy and other specialized treatment that an athletic trainer may not have time, or the expertise, to do.

Trainers also are responsible for collecting injury data — including the specific injury, location of the injury on the body, how many days the athlete was taken out of practice and play, and information on specific treatment. Furutani said that data is instrumental in seeing trends in injuries, which coaches use to change how athletes play and practice.

A “significant difference’

It wasn’t always this way in Hawaii.

In 1991, athletic directors, coaches and professional organizations launched a public education campaign to show parents, athletes and school administrators the importance of athletic trainers.

At the time, there were only five athletic trainers working in Hawaii high schools, and all those schools were private. “That set the standard of what people thought needed to be done for athletes,” Beachy says.

Beachy remembers being the only athletic trainer at a state wrestling tournament and treating mostly athletes from opposing schools. “I was the only one that was qualified to really help these kids,” he says. “And the coaches were going, ‘Wait, we need an athletic trainer.’ So I think they started seeing the benefit.”

At the same time, Bart Buxton, a professor at the University of Hawaii Manoa, surveyed the health care practices and injury rates of high school sports teams.

The study, which Buxton first published in 1991, found “significant differences” between schools with athletic trainers and those without athletic trainers.

In 1993, the Hawaii Legislature responded by providing $1.16 million in funding for a two-year pilot study, which placed 10 athletic trainers in 10 public high schools. Legislators and policymakers wanted to know if the presence of athletic trainers not only reduced injury rates, but presented potential cost savings.

Furutani was one of the first athletic trainers hired.

In those early years, he worked out of a tiny office, sometimes providing care to student athletes from the back of a truck — taping ankles, icing shoulders, making sure athletes were hydrated.

He remembers covering high school state championship baseball games at the University of Hawaii Manoa’s stadium from 8 o’clock in the morning until 11 at night, until the last athlete went home. “It was fun,” Furutani says. “We just did what we had to do.”

Beachy compiled the injury data gathered by Furutani and the nine other athletic trainers into a report for the Legislature. It showed a significant drop in the rate of injury, as well as better health care outcomes and treatment available to student athletes with access to trainers.

“All of that (data) helped their cause to get the funding,” says Ross Oshiro, the coordinator of the sports medicine program at the Queen’s Medical Center in Honolulu and a former athletic trainer.

The next year, the Hawaii Legislature dedicated funding so that all 43 public high schools had an athletic trainer. Beachy, Oshiro and others say that because Hawaii’s public schools are all in one school district, it was administratively easy to add funding for athletic trainers into each school. Four years later, the Legislature added funding ensuring that all but nine of the smallest high schools had two athletic trainers.

Yano said it’s necessary. During the winter season, he and his colleague at Roosevelt attend the practices of four soccer teams, four basketball teams, as well as wrestling and cheerleading teams. Even with two trainers, he said, “You get stretched out a little bit. We could actually use more positions.”

Research drives policy

Athletic trainers say the strong relationships with athletes may make the students more willing to report a concussion or other injury.

“When you’re here every single day you build rapport with them,” Yano says. “It’s actually almost like a family. They have someone to go talk to.

“The key,” he says, “is trust.”

Still, Oshiro said that he and his colleagues constantly battle against “that mentality of ‘suck it up and get back onto the field’,” as they stress to athletes, as well as their coaches and parents, the importance of reporting a possible concussion.

That effort has been aided in the past few years by the increased attention to brain injuries in youth sports. Furutani says that when he first began working as an athletic trainer, concussion monitoring was “not even discussed.”

Now, Oshiro says, the growing body of research about concussions “is really driving” the work of athletic trainers. When he started in the profession, he says, “there was no gradual return to play like the way it is now. There was no guidance as to how to communicate with coaches, with parents.”

Health professionals in Hawaii say concussion prevention, monitoring and treatment have become integral to athletic trainers’ jobs.

“They’re the ones on the front line,” Furutani says. “They’re the ones assessing it on the sidelines, on treating and managing it and determining when they return to play. They’re the ones communicating with everybody else,” including parents, coaches, doctors and school staff. “They’re the key.”

CONCUSSIONS 101

By Amanda Waldroupe/ InvestigateWest

HONOLULU — In addition to putting athletic trainers in every school, Hawaii requires concussion education and protocols for concussion management.

The Hawaii Concussion Awareness and Management Program, or H-CAMP, as it is known, was established in 2010 and is responsible for providing training and education materials to athletic trainers, coaches, school administrator, students and parents.

“Our approach is to educate as many people as we possibly can,” says Nathan Murata, the dean of the University of Hawaii Manoa’s College of Education, which oversees H-CAMP.

H-CAMP oversees the annual education on concussions for coaches, school administrations, educators, student athletes and their parents.

The law also requires that concussed high school athletes are immediately removed from play, that the student must obtain written clearance from a licensed health professional before returning to school and to athletics. It’s similar to Max’s Law, which Oregon lawmakers passed three years earlier, one of the first in the nation to do so.

In 2016, the Hawaii Legislature passed Act 262, extending the protections of Act 197 to all children ages 11 to 18.

The law also allows high schools to conduct baseline neurocognitive testing to compare against neurocognitive testing of students post-concussion.

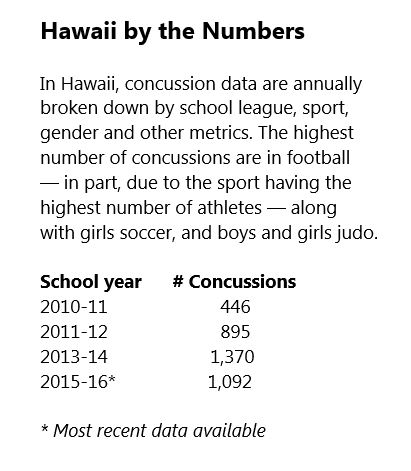

Since its establishment, H-CAMP has collected concussion data from all the public schools in Hawaii.

Oregon law has required schools to track student athletes who suffer concussions since 2010. But unlike Hawaii, Oregon has never analyzed or even collected those records.

Murata says one challenge Hawaii continues to face is how well everyone involved in an athlete’s life — their parents, their coach, athletic trainer, teachers, counselors and administrators — communicate and work together as a student heals from a concussion.

“It’s still a little bit fragmented,” Murata says.

H-CAMP currently is working to create a “return to learn” protocol that is holistic and essentially creates a care team for the athlete.

“It’s not just the athlete and the physician that’s involved with this kid’s concussion,” Oshiro says. “This injury is very different than any other injury that’s out there, because it takes a team approach to manage this child.

“Everybody sees the child in a different light,” Oshiro continues. “So what the parent sees at home, what the teacher sees in the classroom, with the counselor sees with the kid, the athletic trainer, the coach, the physician. Everybody has a different role to play.”

This story has been supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems, http://solutionsjournalism.org.