Tensions between residents of color and police started early in Oregon – and had plenty of support

“Do black lives matter?” Darrell Millner asked, folding his hands and sitting back in his chair, surrounded by towers of books stacked floor-to-ceiling. Books about race. Racism. History. Oregon. “Of course they matter. We shouldn’t even have to question that. But because of this history, we do.”

Oregon, in 1859, was the only state admitted to the union of 33 with a constitutional ban on black residents. Its provincial government had tried threatening black residents with public whipping by a justice of the peace. Later, local law enforcement was ordered to arrest any black adult who remained in the state and hire him out as labor to the lowest bidder.

In 1862, with Union forces claiming victories in the American Civil War, Oregon’s Legislature replaced its forced-labor law with a $5 poll tax from any “Negro, Chinaman, Hawaiian and Mulatto” resident. Sheriffs were tapped to collect the money.

“The relationship between blacks and the justice community has always been defined by the reality that police were assigned to keep the black population under control,” said Millner, a black studies professor at Portland State University. “To a degree, I think that’s why there continues to be that kind of tension between the police community and the black community.”

The state’s formal exclusion was replaced over time with a policy banning people of color from buying property or marrying whites. Klaverns of the Ku Klux Klan formed in pockets across the state from Astoria and Albany to Sherwood and Coos Bay. Police disregarded the beatings and murders of people of color while newspapers fueled the violence.

When Alonzo Tucker was lynched in Coos Bay in 1902, The Oregon Journal reported that the “black fiend” had begged for mercy but did not escape “the death he so thoroughly deserved.”

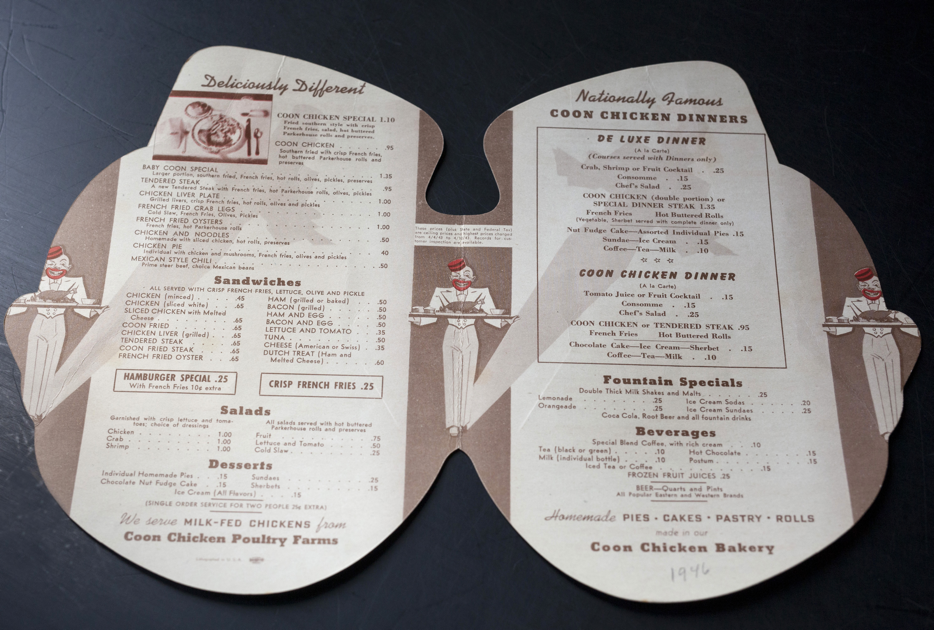

The former Coon Chicken Inn. This photo comes from the City of Portland’s Archives & Records Management office, and was photographed by Jaime Valdez of The Portland Tribune.

When “Birth of a Nation” premiered in Portland in 1915, The Oregonian called the film a “superb achievement.” When an Alabama businessman moved to Grants Pass with three black servants, the Southern Oregon Spokesman headlined its front-page editorial “Let’s keep Grants a White Man’s Town.”

Into the 1940s, most Oregon towns easily answered the Spokesman’s call. Portland, the only city with any significant black community, was 0.6 percent black, according to U.S. Census data. A booming wartime shipbuilding industry, however, would grow its population five-fold within a decade, leading to segregation and growing tensions.

In 1945, influential white residents convened a panel on racial prejudice at the City Club of Portland. Black residents made up less than 2 percent of the county population but, E. C. Halley, acting warden of the Oregon State Penitentiary, told the panel, more than 13 percent of felons that Multnomah County was sending to prison were black.

Portland Police Chief H.M. Niles said his all-white police force wasn’t discriminating against African-Americans. It was his impression black residents committed more crimes. “Chief of Police Niles showed a lack of enthusiasm at the committee’s suggestion of conducting courses in racial tolerance,” the City Club later wrote.

The disparities, though stark, have shrunk in the ensuing decades. Voluntary trainings on racial bias are offered at agencies across the state. A handful of police departments, including Portland, Hillsboro and Corvallis, track the race of people they stop.

The Legislature has passed laws outlawing blatant racial profiling and requiring agencies to maintain clear profiling policies. Yet it has yet to empower any agency to ensure policies are in place, investigate complaints or examine the extent of racial disparities in criminal justice across the state.

Millner said the limping pace of reform signals a need for a new strategy.

“I was born into a country that was racist by public policy, and it’s not any more. And I lived long enough to see a black president,” Millner said. “No way I could have predicted that as a young man. I know that things change. But I know that things don’t change by themselves. Things change because people decide to do things in a different way.”