Rivers in America have stopped catching on fire. Big industrial polluters have been reined in. Overall, water quality has improved under the Clean Water Act.

But for all of its successes, the landmark environmental law was never designed to control contaminants that emerged after its 1972 passage. These pollutants are affecting the environment in new and different ways.

Consider the feminized fish of Puget Sound.

That’s something Lyndal Johnson has been doing a lot of lately. Johnson is a fisheries biologist and toxicologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. She and a team of scientists were out sampling English sole –- a flatfish common to the sound’s Elliott Bay — when they noticed something, well, fishy.

“These fish in Elliott Bay, when all the other fish had completed spawning, ready to go home, it’s all over for them, the Elliott Bay were still ripe and still had eggs that they had not yet spawned.”

The team went back and sampled more fish around Puget Sound and found even creepier results. Some male fish were producing a protein called vitellogenin. Vitellogenin is a protein used to make egg yolks.

That’s not something you want to see in male fish, says Jim West, a senior scientist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. West was with Lyndal Johnson when they found the weird fish.

“It’s an indication that they’ve been exposed to something, some chemical, that is essentially feminizing them.”

These fish weren’t dying. From the outside, they didn’t even look different. But there were striking changes going on inside them.

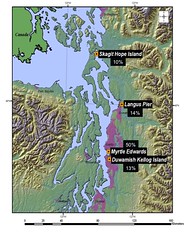

The team took more samples. The results: almost half of the 49 male English sole they tested at the Elliott bay sight on the Seattle waterfront were producing the female egg yolk protein. Elevated egg protein levels were also found at sample sites in Tacoma’s Commencement Bay and near Everett.

Perhaps more disturbingly, the researchers found similar results in the endangered juvenile chinook salmon they tested at the Elliott Bay site.

The fish here are not alone. The U.S. Geological Survey collected bass from more than 100 rivers around the country. One third of those fish showed signs of feminization and intersex characteristics.

“Mainly what we saw were testicular oocytes in what would otherwise be normal testicular tissues,” says Don Tillitt, a toxicologist with the US GS in Columbia, Missouri.

Basically, testes with eggs in them.

Pinpointing the exact chemicals that are causing this feminization and intersex development has been the biggest challenge for scientists so far. But many believe a group of chemicals known as endocrine disruptors are to blame.

They’re sort of like hormone imposters. They act like normal hormones – estrogen or testosterone for example – and mess with the body’s natural hormonal messaging system.

Bisphenol A is probably the most well-known chemical in this family. It’s commonly referred to as BPA. You’ll find it in certain plastics, the liners of canned goods, epoxies – even kids toys.

Synthetic estrogen from birth control pills has also been shown to feminize fish.

These chemicals get into our bodies and then end up in wastewater. Tillitt says that wastewater, even though it’s been treated, carries some of them into nearby waterways, and can negatively affect immune system response and reproductive health in fish.

“It’s not surprising,” he notes, “that in certain locations, downstream from wastewater treatment plants, are some of the most common locations where we can find intersex (fish).”

The problem is: even the most modern wastewater treatment facilities aren’t specifically designed to remove this new class of chemicals.

Tillitt says regulation and treatment systems are going to have to adapt to manage endocrine disrupting chemicals, though it won’t be easy or cheap.

Environmental agencies here have known about endocrine disrupting chemicals and some of their impacts on animals since the 90’s.

“We recognize this is a problem but we don’t have it under control,” says Scott Redman, a senior science program specialist with the Puget Sound Partnership. The governmental agency lists endocrine disrupting chemicals as a threat to Puget Sound and says they will eliminate the harm to fish by 2020. But their plan of attack is somewhat hazy.

“We have efforts to control stormwater and to improve wastewater,” Redman says, “Those we think will help but we may need more targeted efforts to the specific chemicals that are causing this harm and we haven’t grappled yet with what those specific actions may be.”

A major national health study found Bisphenol A in the urine of more than 90 percent of Americans. It’s also prevalent in stormwater samples collected in King County, Wash.

After years of debate the federal government banned the use of bisphenol A in baby bottles and sippy cups this summer. It’s too soon to say if that ban has had any effect.

Jim West says these new chemicals present challenges that the authors of the Clean Water Act could never have seen coming. And that calls for strong action and fresh thinking.

“I like to say that the fish are telling us what the problems are,” he says, “if we’re out there looking.”